Scroll

↓

December 7, 1941

Japan attacks Pearl Harbor

Japan attacks the Pearl Harbor military base in Hawai’i, killing 2,403 people. The F.B.I. begins arresting Japanese immigrants identified as community leaders and potential saboteurs to the U.S. government. Within 48 hours, 1,291 are arrested.

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

December 8, 1941

U.S. takes swift action

The next day, President Franklin D. Roosevelt asks Congress to declare war on Japan. Soon after, the Justice Department closes its borders with Canada and Mexico to all people of Japanese ancestry, regardless of their citizenship. A few weeks later, it authorizes search warrants for contraband materials in any home in which an “enemy alien” resides. Over the next few months, thousands of Japanese American homes are raided for anything that might be perceived to be a weapon.

February 19, 1942

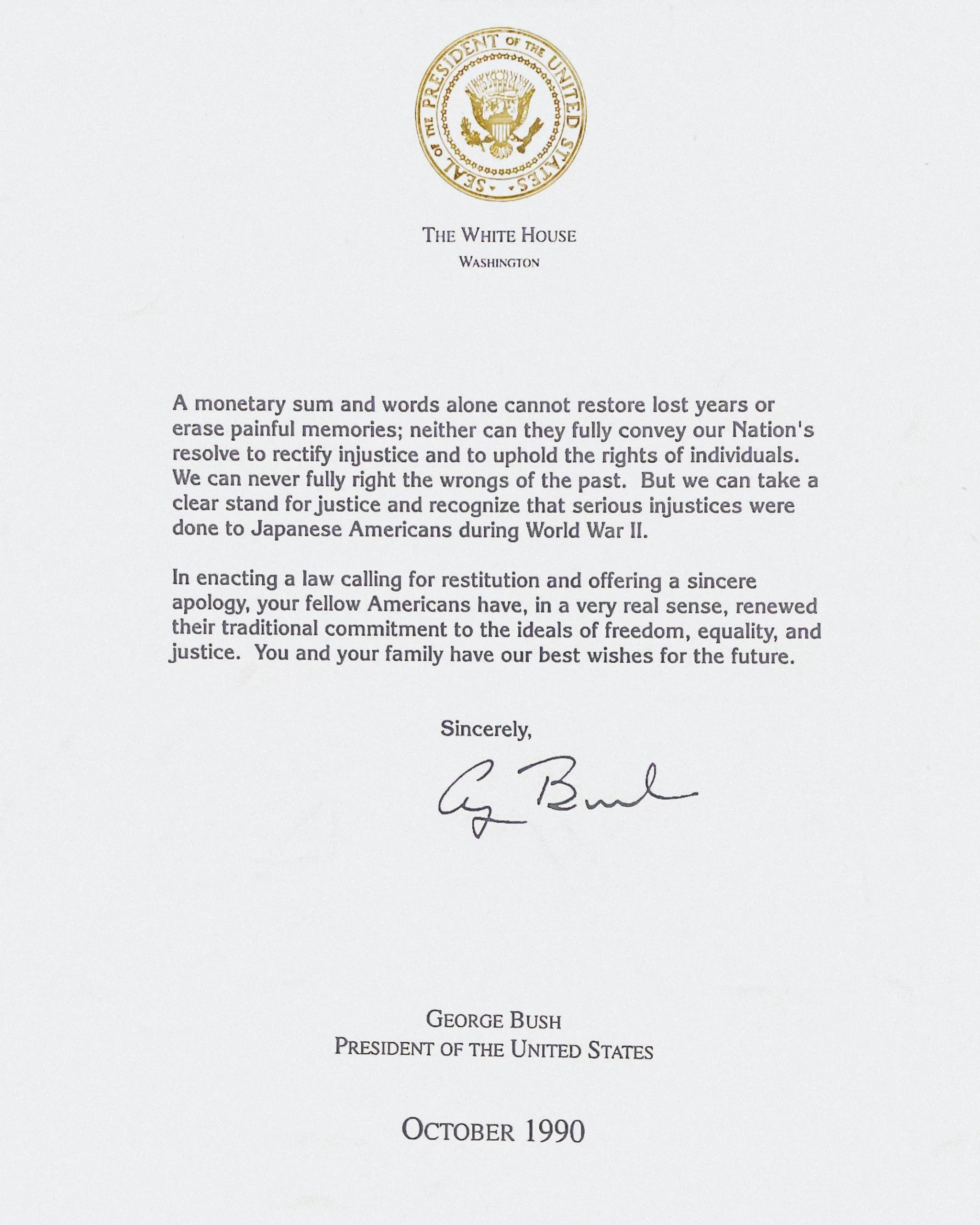

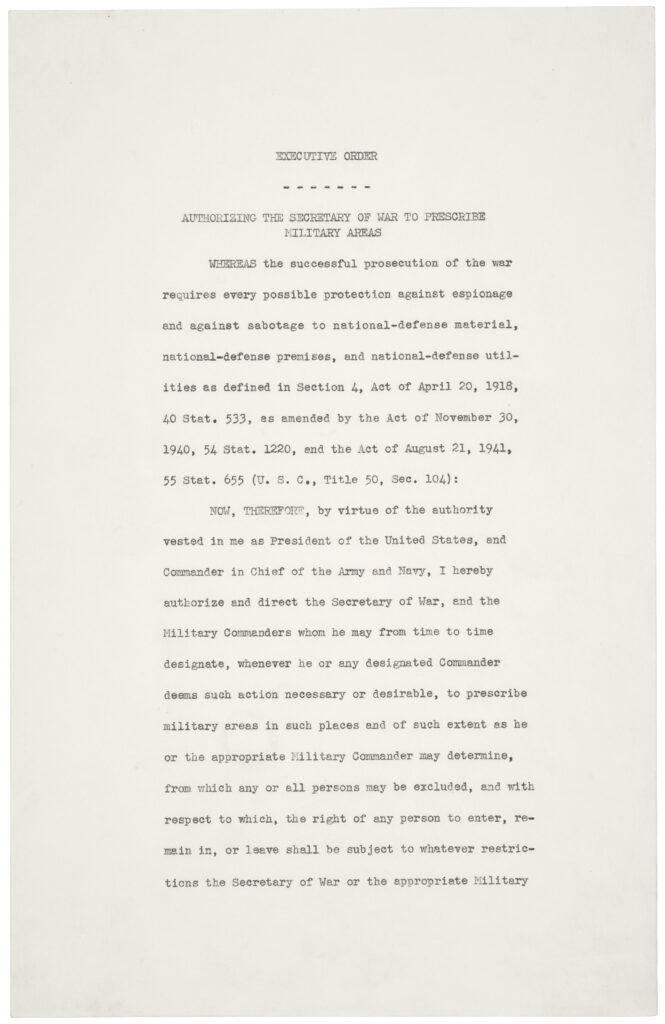

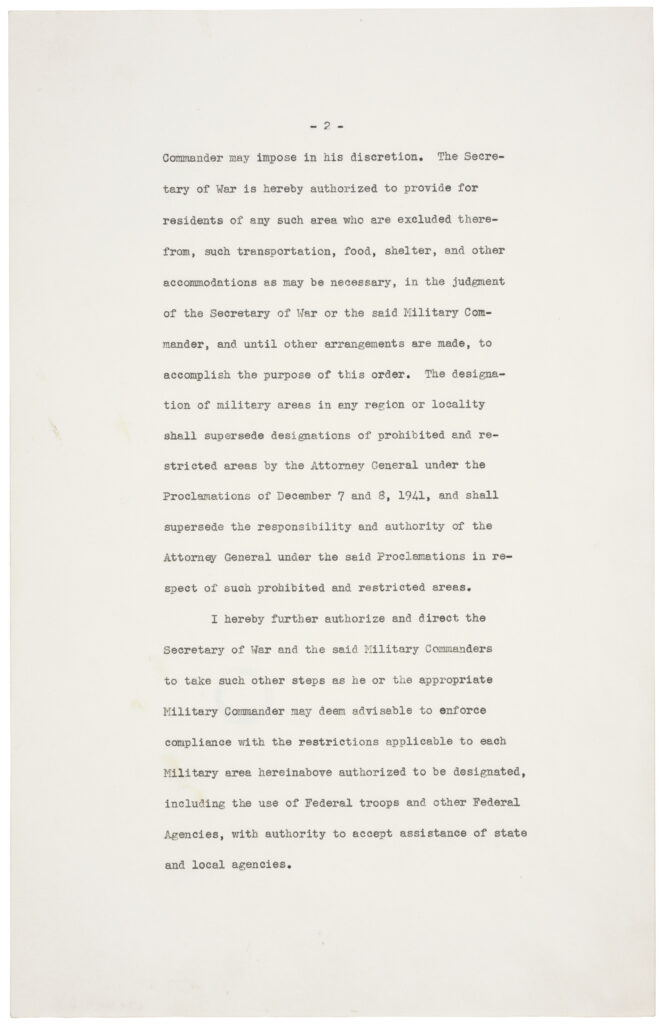

President Roosevelt issues Executive Order 9066

President Franklin D. Roosevelt signs Executive Order 9066, which authorizes military authorities to prescribe “military areas” and “exclude” civilians from those areas. The order does not specifically mention people of Japanese ancestry, but they are the only group to be displaced as a result of it.

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

February 25, 1942

The first Japanese Americans are displaced

The U.S. Navy orders all Japanese Americans living on Terminal Island in the Port of Los Angeles—totaling about 500 families—to leave within 48 hours. Many Terminal Island residents work in the fishing industry and have no choice but to sell their fishing boats and other equipment in the short amount of time they have before being displaced from their homes.

March 1, 1942

Assembly Centers open

The Wartime Civil Control Administration opens 16 “assembly centers,” or makeshift concentration camps designed to provide temporary housing until the more permanent concentration camps are completed. Many assembly centers are situated on large fairgrounds or racetracks to reduce the need to build extra housing. At the racetracks, horse stables are repurposed as living quarters.

March 2, 1942

West Coast becomes a military exclusion zone

General John L. DeWitt, head of the Western Defense Command, designates parts of the West Coast into military zones from which people of Japanese ancestry would be excluded. A curfew goes into effect in these areas from 8pm to 6am, and movement becomes tightly restricted.

While many Japanese Americans feel they have no choice but to comply, a lawyer named Minoru Yasui, who questioned the legality of these curfews, turns himself into a Portland police station to make himself a legal test case and bring these curfew regulations to court.

March 24, 1942

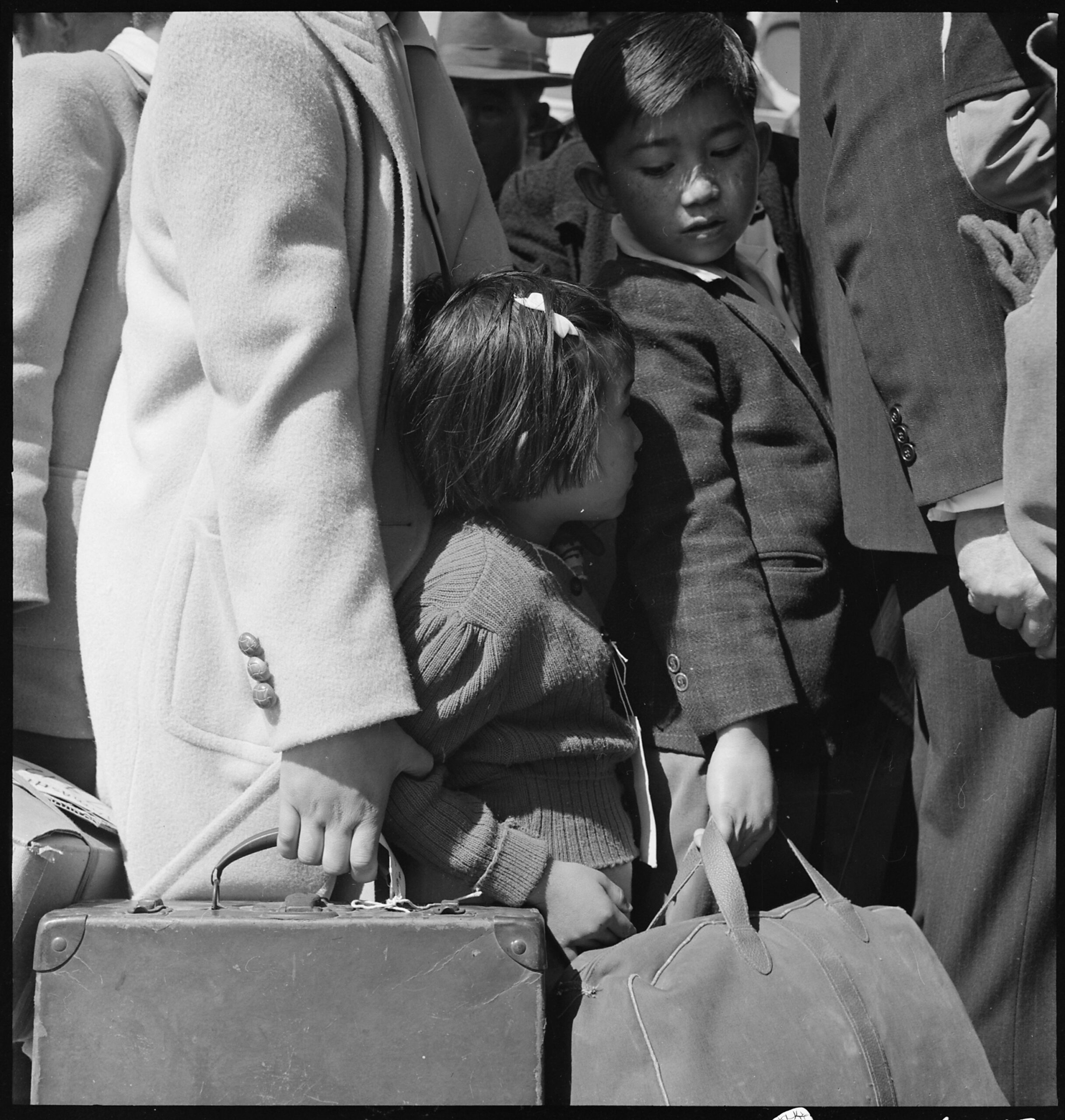

Mass removal begins

The first Civilian Exclusion Order is issued, giving families in Bainbridge Island up to one week to prepare for removal from their homes. This is followed by a series of exclusion orders—108 orders total—that sends tens of thousands of Japanese Americans into concentration camps.

Some Japanese Americans famously resist the exclusion orders. Fred Korematsu refuses to comply with the exclusion order and is arrested on a street corner. Gordon Hirabayashi—still a college student—turns himself in to the authorities with a four-page statement explaining why he would not submit to the exclusion order on constitutional grounds.

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

May 1, 1942

From horse stable to concentration camp

The months-long process begins to transfer incarcerees from their assembly centers to the more permanent War Relocation Authority concentration camps. There are 10 camps total: Amache, Gila River, Heart Mountain, Jerome, Manzanar, Minidoka, Poston, Rohwer, Topaz and Tule Lake.

Escorted by armed soldiers, incarcerees were herded onto buses and trains and sent to their designated concentration camps, which were scattered in remote areas across the country. With the window shades pulled down, many had no idea where they were headed over the course of their days-long journeys and were stunned by the stark landscape and unforgiving temperatures upon their arrival.

At this point, barely three months had passed since the executive order. Many of the camps are hastily built or incomplete, missing basic infrastructure like plumbing and electricity.

Spring of 1942

Government encourages “resettlement“

Faced with the mounting costs of incarcerating 120,000 people, the War Relocation Authority implements “resettlement” programs to move “loyal” Japanese American incarcerees out of camp and encourage them to relocate to areas outside of the military exclusion zone. Applicants are required to pass a F.B.I. background check, secure an outside sponsor and navigate a time-consuming application process to be granted permission to leave camp and work as farm laborers, attend college and find employment in designated areas.

January 1, 1943

U.S. begins recruiting Japanese American soldiers

The War Department announces the formation of a segregated unit of Japanese American soldiers and calls for volunteers from the camps. Embittered by their incarceration, less than 1,000 incarcerees volunteer at first.

Eventually, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team is formed, and enlistment steadily grows. Over the course of the war, the unit goes on to receive 4,000 Purple Hearts, 8 Presidential Unit Citations, 559 Silver Stars, and 52 Distinguished Service Crosses among many other decorations. The 442nd Regimental Combat Team is the most decorated unit in U.S. military history for its size and length of service.

Spring of 1943

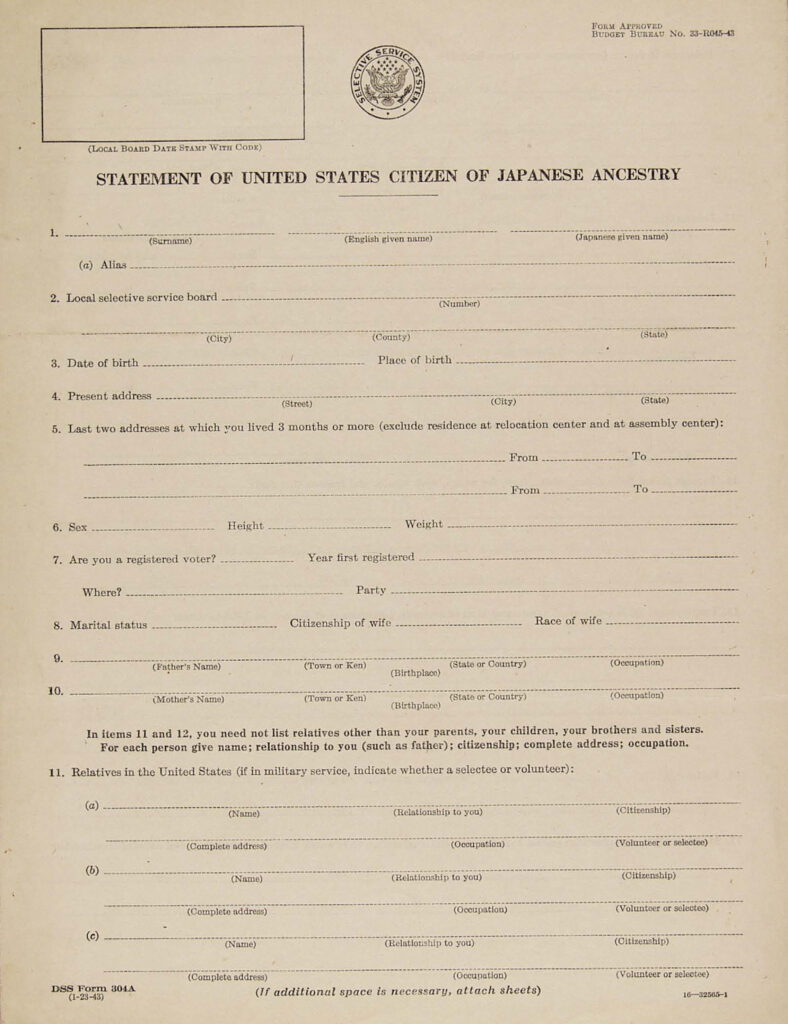

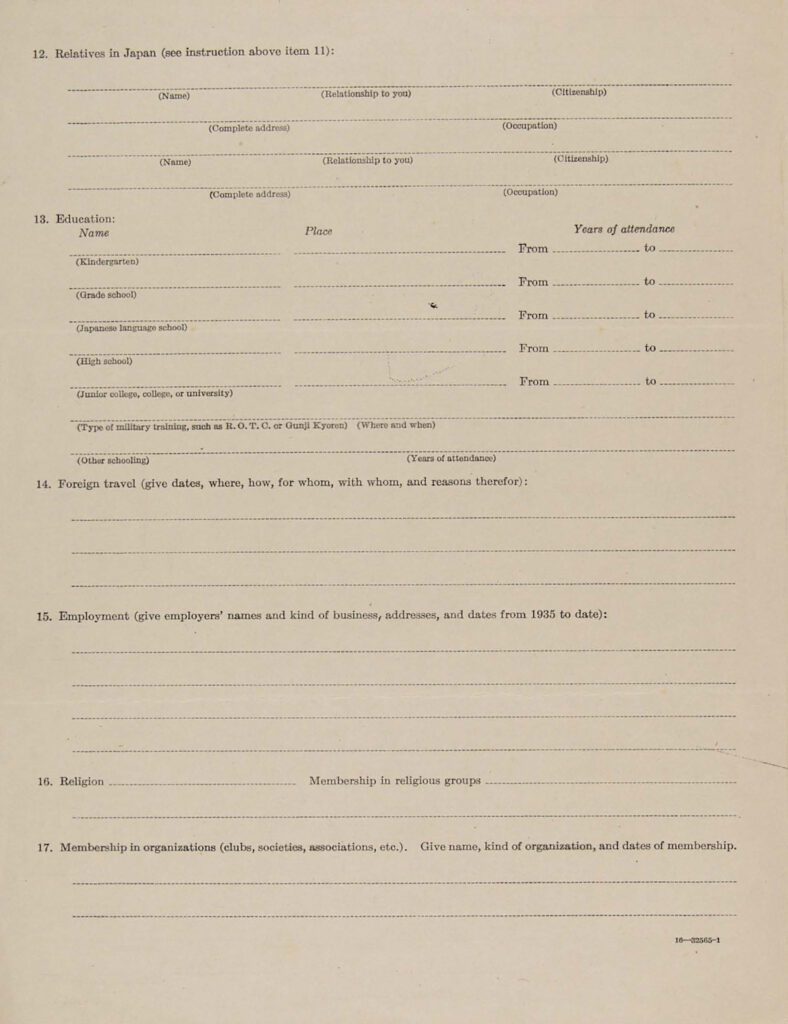

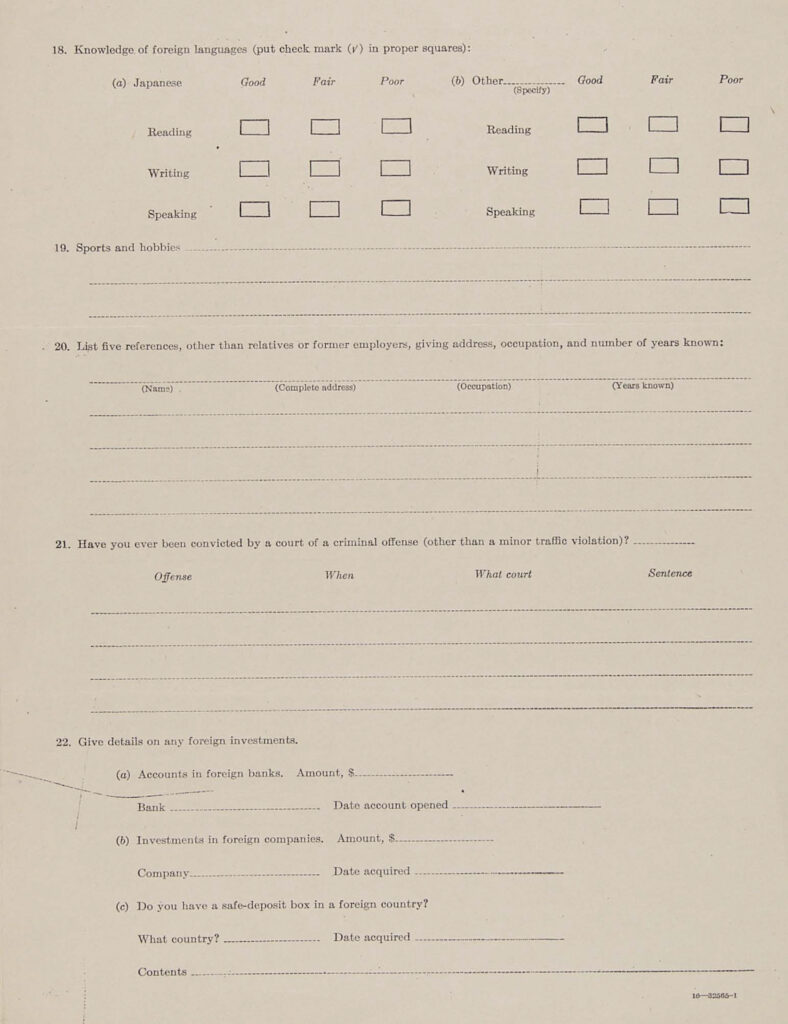

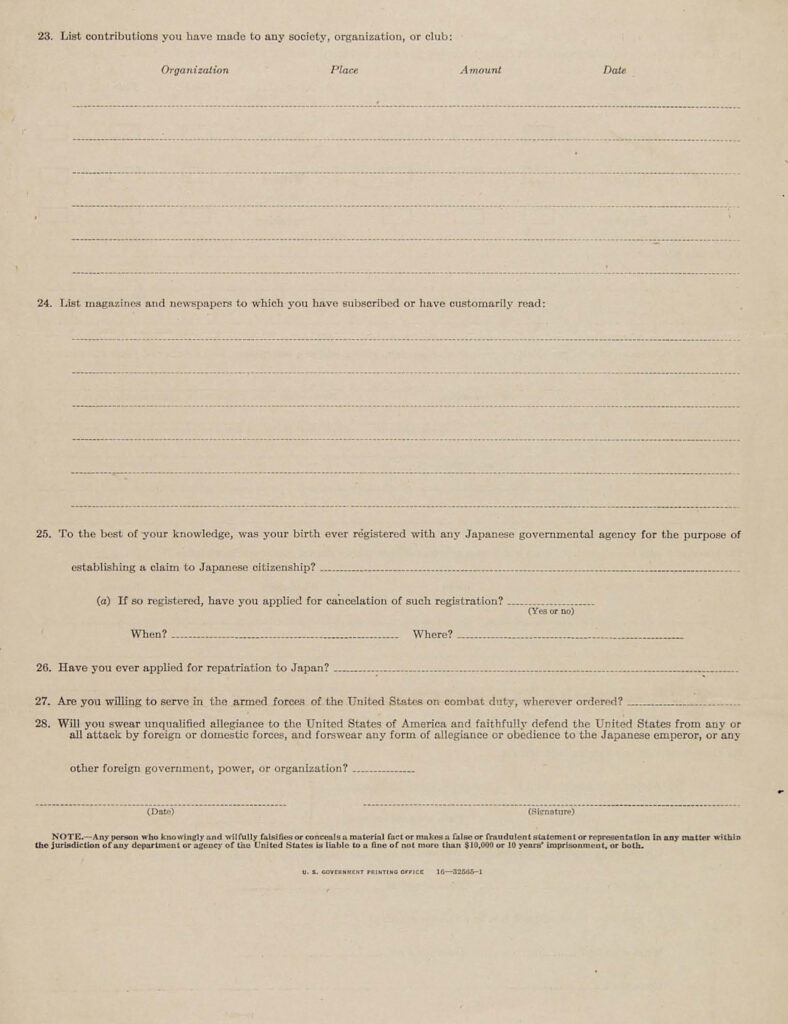

A Test of “Loyalty”

Struggling to attract more resettlement applicants, the War Relocation Authority joins forces with the War Department to devise a more streamlined application called the Application for Leave Clearance, also known as the controversial “loyalty questionnaire.” Completing this questionnaire is now mandatory for all incarcerees over the age of 17, and it provides the War Relocation Authority a means to identify “loyal” incarcerees for resettlement and separate “disloyal” incarcerees from the rest of the camp population by sending them to the Tule Lake Segregation Center.

Question #27 asked: “Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty, wherever ordered?”

Question #28 asked: “Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attacks by foreign or domestic forces, and foreswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor, or any other foreign government, power or organization?”

The first question troubled incarcerees who feared leaving vulnerable family members behind in the camps. It also offended Japanese Americans who had previously served in the U.S. forces but were discharged or reclassified to IV-C, a classification reserved for aliens. The second question perplexed U.S.-born Japanese Americans who never had any allegiance to the Japanese emperor in the first place. It also raised concerns for foreign-born Japanese immigrants who feared answering “yes” would render them stateless refugees, since they were not yet able to naturalize into U.S. citizens at this time.

The War Relocation Authority labeled those who answered “no” or refused to give an affirmative answer to these two questions as “disloyal” and sent them to the Tule Lake Segregation Center. This group—known as “no-no’s”—made up about 12,000 of the 78,000 incarcerees surveyed. For decades after the war, “no-no’s” were stigmatized as traitors by the Nikkei community and the general public.

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

September 1, 1943

Segregation begins

“Loyal” incarcerees from Tule Lake are transferred to other camps and “disloyal” incarcerees from other camps begin to arrive at Tule Lake. The Tule Lake population grows from 15,276 to 18,789. Though additional barracks are built, the camp population balloons at almost 4,000 people over its intended capacity. Tensions rise between new arrivals and the existing incarcerees.

January 20, 1944

Men are drafted from the camps

Struggling with low volunteerism from the camps, the War Department reinstates a military draft from 1940—from which Japanese Americans were categorically excluded after the Pearl Harbor attack—on Japanese American men from the camps. The military emphasizes that this is a restoration of equality for the Nisei because they would “again be classified […] on the same basis as other citizens.” In reality, however, Japanese Americans are drafted into a racially segregated combat unit and still excluded from serving in the Navy. While most incarcerees comply, a few hundred resist and face federal charges.

July 1, 1944

President authorizes denaturalization

Although incarcerees had been requesting repatriation or expatriation back to Japan since as early as 1942, the number of requests explode after the draft reinstatement, topping out at nearly 20,000, or 16 percent of the total incarcerated population. In response, the President signs the Denaturalization Act of 1944, which allows U.S. citizens to renounce their citizenship. Many choose renunciation as a form of protest to their unconstitutional treatment, while others denaturalized fearing for their safety and separation from their families after the war. Between 1944 and 1946, 5,589 U.S. citizens renounce their citizenship.

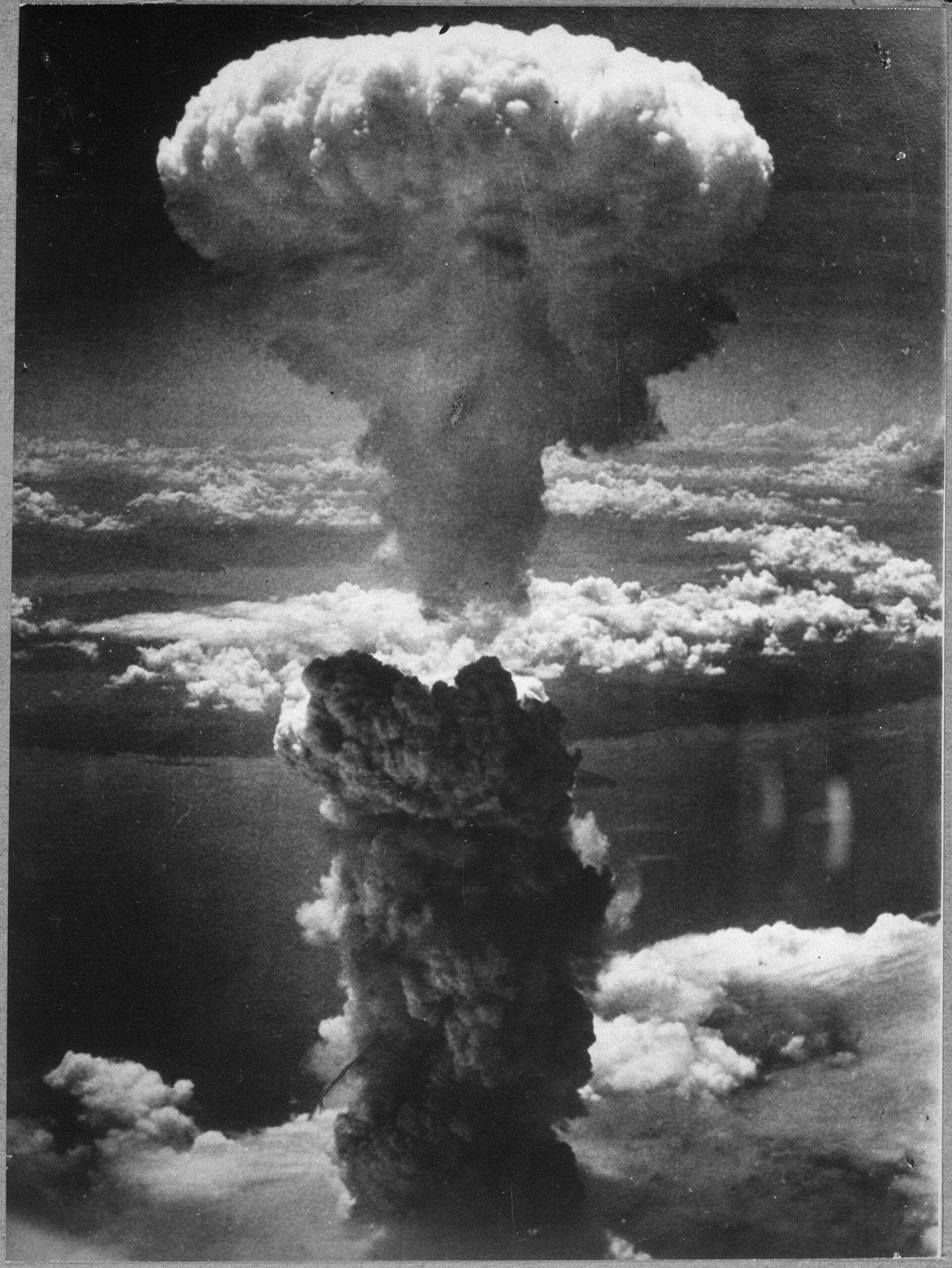

August 14, 1945

Japan surrenders

The U.S. drops the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Three days later, it drops a second atomic bomb on Nagasaki. Japan surrenders on August 14.

At this point, some 44,000 incarcerees still remain in the camps. Many refuse to leave. Realizing that they have few options for survival in a war-ravaged Japan, those who renounced their citizenships begin to seek ways to cancel their renunciation. Civil rights attorney Wayne M. Collins begins advising Tule Lake renunciants and embarks on a 23-year-long campaign filing thousands of court cases to restore the renunciants‘ citizenships. The concentration camps begin to close one by one after the end of the war.

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

March 20, 1946

The last camp closes

On November 13, 1945, just two days before a ship carrying renunciants is set to leave for Japan, Wayne M. Collins secures a court order preventing their deportation until they can appear before a judge. Over the next four months, the Department of Justice conducts administrative hearings at the Tule Lake Segregation Center. Seven months after the end of the war, the last War Relocation Authority concentration camp closes.

Some Japanese Americans attempted to return to their former homes on the West Coast. However, many found their properties had been lost, sold, or vandalized during their absence.

As part of their resettlement programs, the War Relocation Authority established field offices in the Midwest and East Coast to encourage Japanese Americans to relocate to these areas and reduce the concentration of Japanese Americans on the West Coast. Seeking potential job opportunities, a significant number of Japanese Americans moved to cities like Chicago, New York, Denver, and Salt Lake City after the war.

Many incarcerees struggled to find housing. Some lived in hostels, boarding houses and public housing projects while others rented out garages of other people’s homes and pitched tents on their employer’s property to get back on their feet.

After the war, Elizabeth Okayama’s father traveled from Heart Mountain to Los Angeles to check on their family home and business. “When he went back to look at the place where we lived, he saw, in business windows, signs saying ‘No Japs Allowed’,” Elizabeth says. “My father was determined not to take his family back to that racist environment.” Elizabeth’s family ultimately decided to start their lives over in Chicago. To learn more about Elizabeth’s experience, click here.

Prior to their incarceration, Irene Shikibu Shigaki’s family had left their home in the care of a friend to rent out to tenants while they were gone. However, when they returned to Seattle, the tenants refused to leave. “My family lived literally a block down the street from their own house in the Japanese language school, which had been set up as a hostel for families returning to Seattle,” says her niece Erin.“That was a strange, almost torturous thing. They could see their house if they looked up the street.” To learn more about Irene’s experience, click here.

Prior to their incarceration, Mary Higuchi’s family had stored their belongings in a barn. When they returned after the war, they found the barn empty. “There was nothing there. Nothing except for broken boxes, empty boxes. Maybe a few broken dishes,” she says. With nowhere to return to, Mary’s family moved to a house with no indoor plumbing. It took Mary’s family nearly a decade to save enough money to put a down payment on farmland that they could call their own. To learn more about Mary’s experience, click here.

July 2, 1948

An attempt at reparations

President Harry S. Truman signs the Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act, which allows former incarcerees to file claims for lost property as a result of their incarceration. However, the Act requires detailed documentation that many incarcerees are unable to provide due to the chaotic circumstances of their removal. It also does not compensate for other losses like lost income and personal injury. In total, the government pays out $38 million to settle damage claims—a small fraction of the $132 million in total filed claims, let alone the actual losses of Japanese Americans, which is estimated to be over $400 million. Many families pay more in lawyer’s fees than they receive in compensation.

1967-1988

A Movement Is Born

A few years after the last claim is settled through the Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act in 1965, former incarcerees Raymond Okamura and Edison Uno organize a grassroots campaign to demand reparations for all former incarcerees. As support for redress steadily grows, the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians is established, calling for a congressional committee to investigate the detention program and the constitutionality of Executive Order 9066. The nine-member committee holds hearings in major U.S. cities and collects testimonies from more than 750 witnesses.

December 27, 1969

The First Pilgrimage

Drawing inspiration from the Civil Rights Movement and leaders within their own community—notably, Buddhist minister Sentoku Maeda and Christian minister Shoichi Wakahiro, who journeyed back to Manzanar every year after the war to honor those who died there—Japanese American student activists lead the first organized pilgrimage back to a former concentration camp. This inaugural event, attended by around 150 people, inspires a decades-long tradition that continues at most of the 10 former concentration camps today.

Courtesy of the Manzanar National Historic Site and the Evan Johnson Collection

February 24, 1983

A call for reparations and a formal apology

The Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians issues its report, Personal Justice Denied, on February 24 and its Recommendations, on June 16. The former is a 467-page report concluding that Executive Order 9066 was not justified by military necessity but rather was the result of “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” The latter calls for a presidential apology and a $20,000 payment to each surviving incarceree.

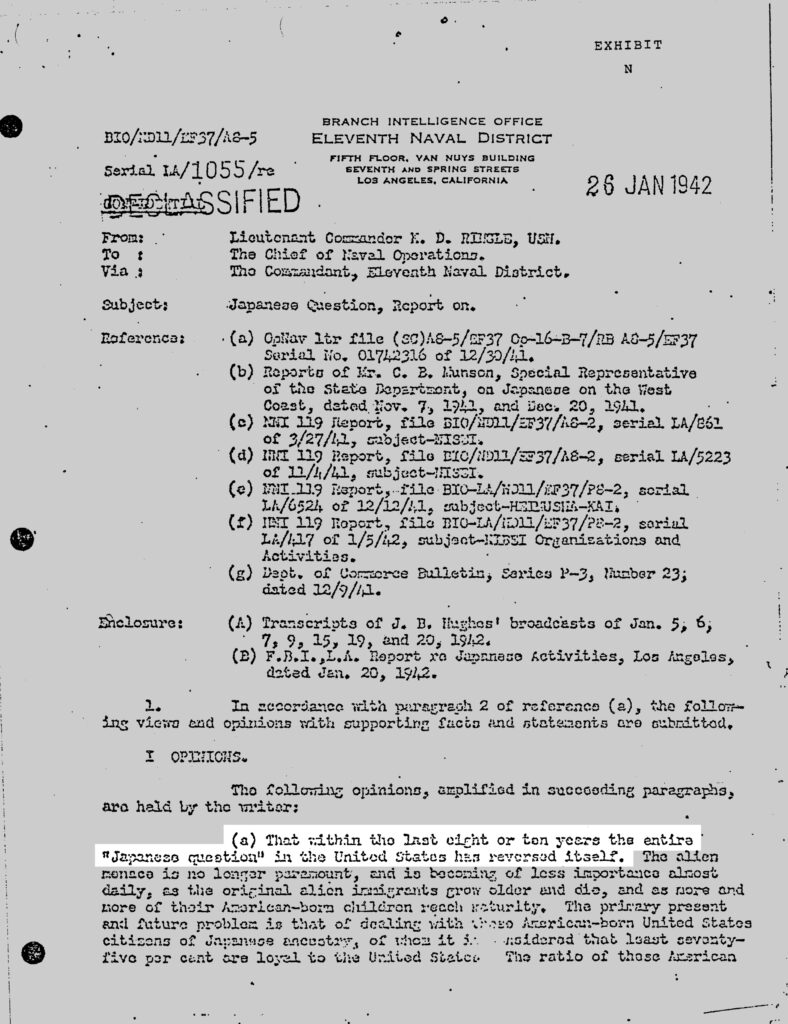

1983-1988

Damning Evidence

Researchers Peter Irons and Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga uncover wartime documents showing that government attorneys had withheld, altered, and destroyed evidence favorable to Japanese Americans during World War II, while falsely claiming they were national security threats. This discovery challenges the landmark Supreme Court decisions in the cases of Gordon Hirabayashi, Fred Korematsu, and Minoru Yasui, and plays a crucial role in educating the public about the flawed justification for the forced removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans.

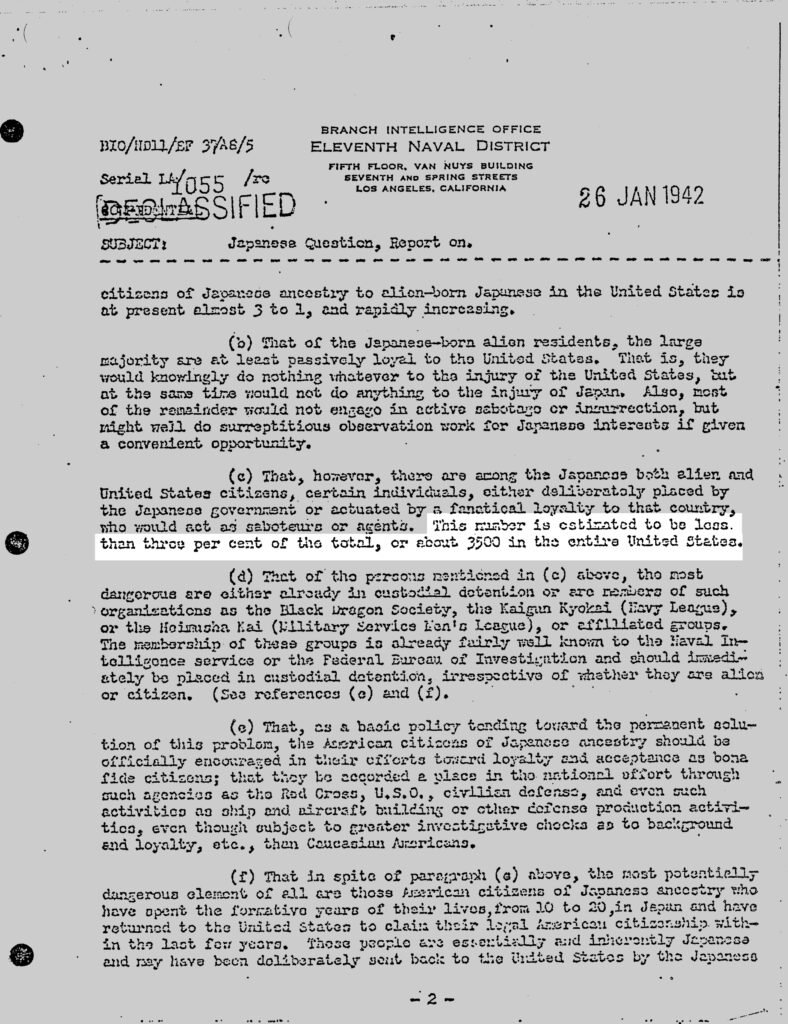

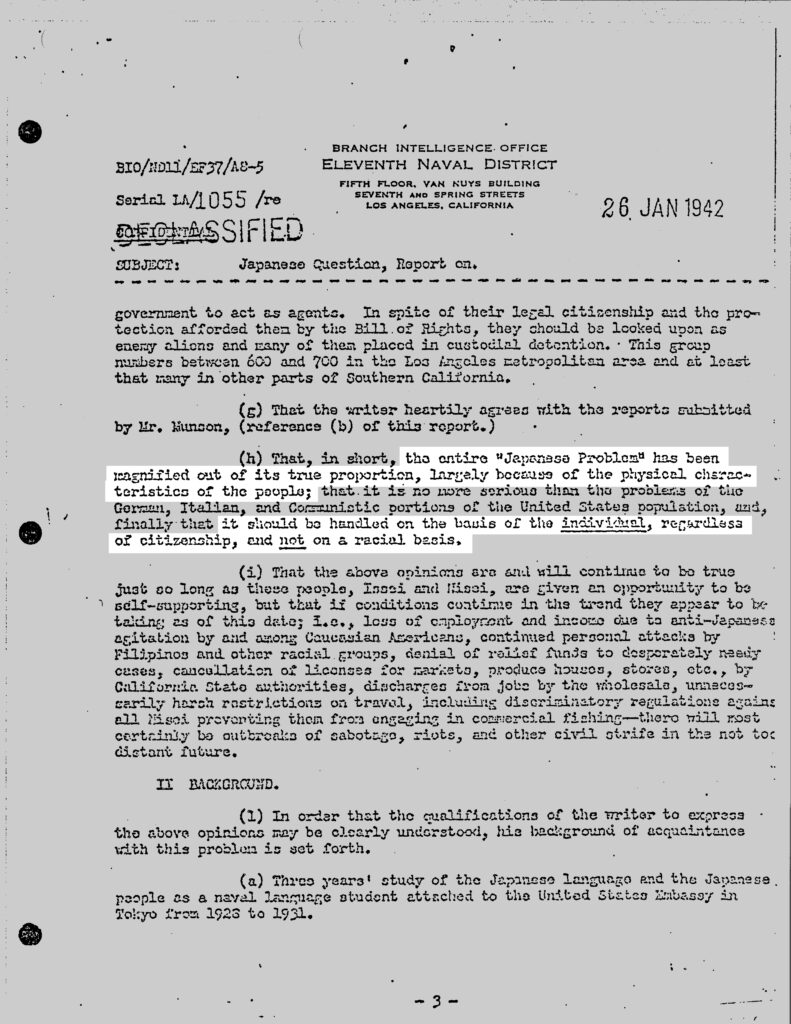

Intelligence reports from the Office of Naval Intelligence (O.N.I.) indicated that the O.N.I. had conducted thorough investigations and found no evidence of espionage or sabotage among Japanese Americans, directly contradicting the government’s claims used to justify their mass incarceration. In a January 1942 memo, Lt. Kenneth Ringle of the Office of Naval Intelligence concluded that “the entire ‘Japanese problem’ has been magnified out of its true proportion, largely because of the physical characteristics of the people.”

Furthermore, internal documents from the U.S. Department of Justice revealed that some government officials, including then-Attorney General Francis Biddle and Assistant Attorney General Edward Ennis, were aware that the military’s claims of “military necessity” for the exclusion and incarceration of Japanese Americans were unfounded.

The researchers also found that key government reports like General John L. DeWitt’s Final Report, Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 had been altered to remove evidence that contradicted the justification for the mass incarceration. They also uncovered a memorandum revealing that Charles Fahy, the solicitor general who argued the cases before the Supreme Court, was aware of the O.N.I. reports and other evidence that contradicted the government’s position but chose not to disclose them to the Court. This withholding of evidence constituted a violation of the legal duty to provide the Court with all relevant information.

Courtesy of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians

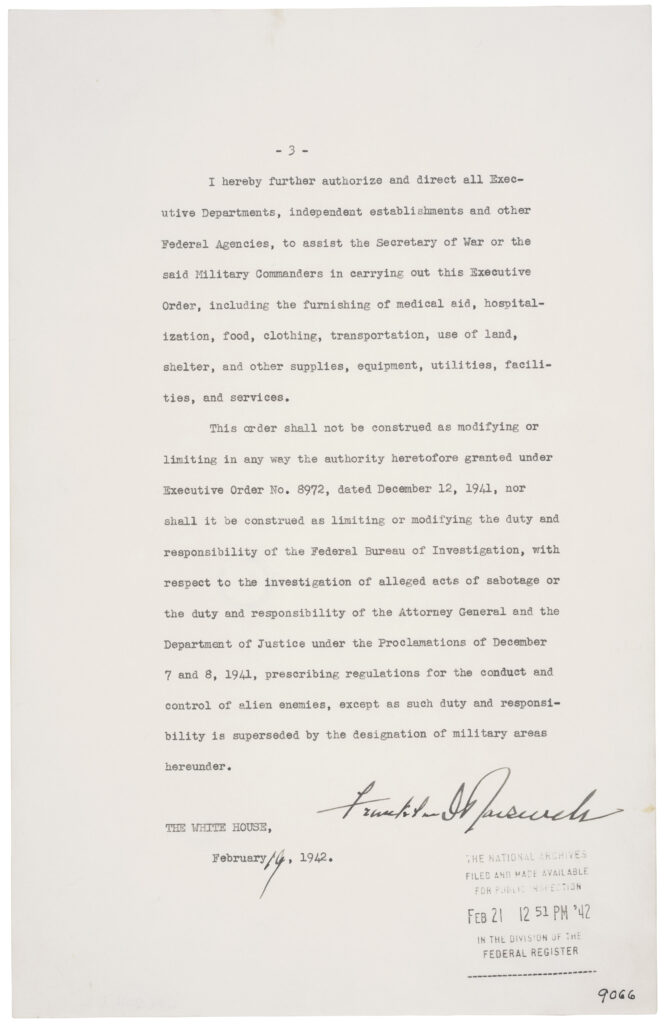

August 10, 1988

Congress passes the Civil Liberties Act of 1988

President Ronald Reagan signs the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which apologizes for the wrongful incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II and provides $20,000 in compensation to each surviving incarceree. The Act states that “a grave injustice was done to both citizens and permanent resident aliens of Japanese ancestry” and that “these actions were carried out without adequate security reasons and without any acts of espionage or sabotage, and were motivated largely by racial prejudice, wartime hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.”