“Our mother had to deliver our sister […] in the crude medical facility on the Merced County fairgrounds just a month before we were all put on old trains to Colorado.”

— Gary T. Ono

Gary T. Ono

Sansei

Gary T. Ono was born and raised in San Francisco to a Kibei father and a Nisei mother. He grew up above Benkyodo, a Japanese confectionery store founded by his grandfather Suyeichi Okamura in 1906. Gary was named after Geary Street, where the store was located.

On the day of the Pearl Harbor attack, Gary and his family were enjoying a Sunday drive in Marin County for his mother’s birthday. “The car’s AM-radio was playing some of the top-ten popular hits,” says Gary. “Nearing noon, a news bulletin […] abruptly interrupt[ed] the music […] ‘Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Hawaii is being attacked by a wave of Japanese warplanes!’” The family quickly returned home to San Francisco’s Japantown.

Shortly after, Gary’s grandfather was arrested by the F.B.I., and a few months later, Executive Order 9066 was issued. At first, residents in military exclusion zones like San Francisco were permitted to voluntarily relocate to areas outside of these zones. Gary’s family moved to his grandfather’s farm in Turlock, CA. However, the government soon expanded the exclusion zone to cover the entire West Coast, and the family was sent to the Merced Assembly Center. “Our mother had to deliver our sister, Sandra Yoko on August 5, 1942, in the crude medical facility on the Merced County fairgrounds, just a month before we were all put on old trains to Colorado,” Gary recalls.

After a grueling three-day train ride, Gary’s family arrived at Amache, which was still under construction. His father joined a volunteer crew to complete the camp before winter. Gary later discovered his father’s contribution when he visited Amache in 2008 and found his father’s signature on a concrete pedestal at a bathhouse.

In early 1943, Gary’s bilingual father was hired by the British Political Warfare Mission (B.P.W.M.) to translate and broadcast propaganda material to Japan from Denver. That summer, Gary, his mother, and siblings left Amache to join his father. Soon after, Gary’s mother gave birth to his brother Victor, but she contracted tuberculosis and was hospitalized in Boulder, CO. Gary and his siblings were sent back to Amache, where they were separated among various relatives. “We four were spread out amongst different family members in three different concentration camp barracks without our parents for over half of a year—Stanley and I with bachan Aiko Okamura, Sandi with auntie Yukiko Okamura Masuoka and baby Victor with ojichan Kinsuke and bachan Kotora Ono,” Gary says. “I hate to admit it, but I was a bit of a ‘cry-baby’ at [this time]. Was I suffering from separation anxiety?”

After months in the sanitarium, Gary’s mother returned to Amache, and by early 1945, B.P.W.M. operations in Denver were shut down. Gary’s father was transferred to San Francisco, where he resumed broadcasting, this time urging Japan to surrender. The family rejoined him in San Francisco in the spring of 1945. Reflecting on the subsequent bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Gary says, “I think maybe the Hiroshima bombing would have accomplished [ending the war], but not the additional bomb dropped on Nagasaki. That, I and many believe, was a ghoulish scientific experiment to test a different type of nuclear device.”

Returning after the war, the Ono family moved into a building nearby Japantown and worked to rebuild Gary’s grandfather’s legacy business Benkyodo from the ground up, with the help of the Ono and Masuoka families. “My mother and father and aunt helped their parents and in-laws restart Benkyodo,” says Gary. “Slowly, the rest of Nihonmachi started to grow, and people moved back in, and so business then picked up again.”

Decades later, with the passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, Gary and his family received their reparations. Gary used his check to fund Calling Tokyo, a documentary about his father’s B.P.W.M. service. “I always said, ‘We Sansei don’t deserve this. It’s the Nisei and the people who passed on,’” Gary says. “But I accepted it. I thought, ‘let’s use it for a better purpose.’”

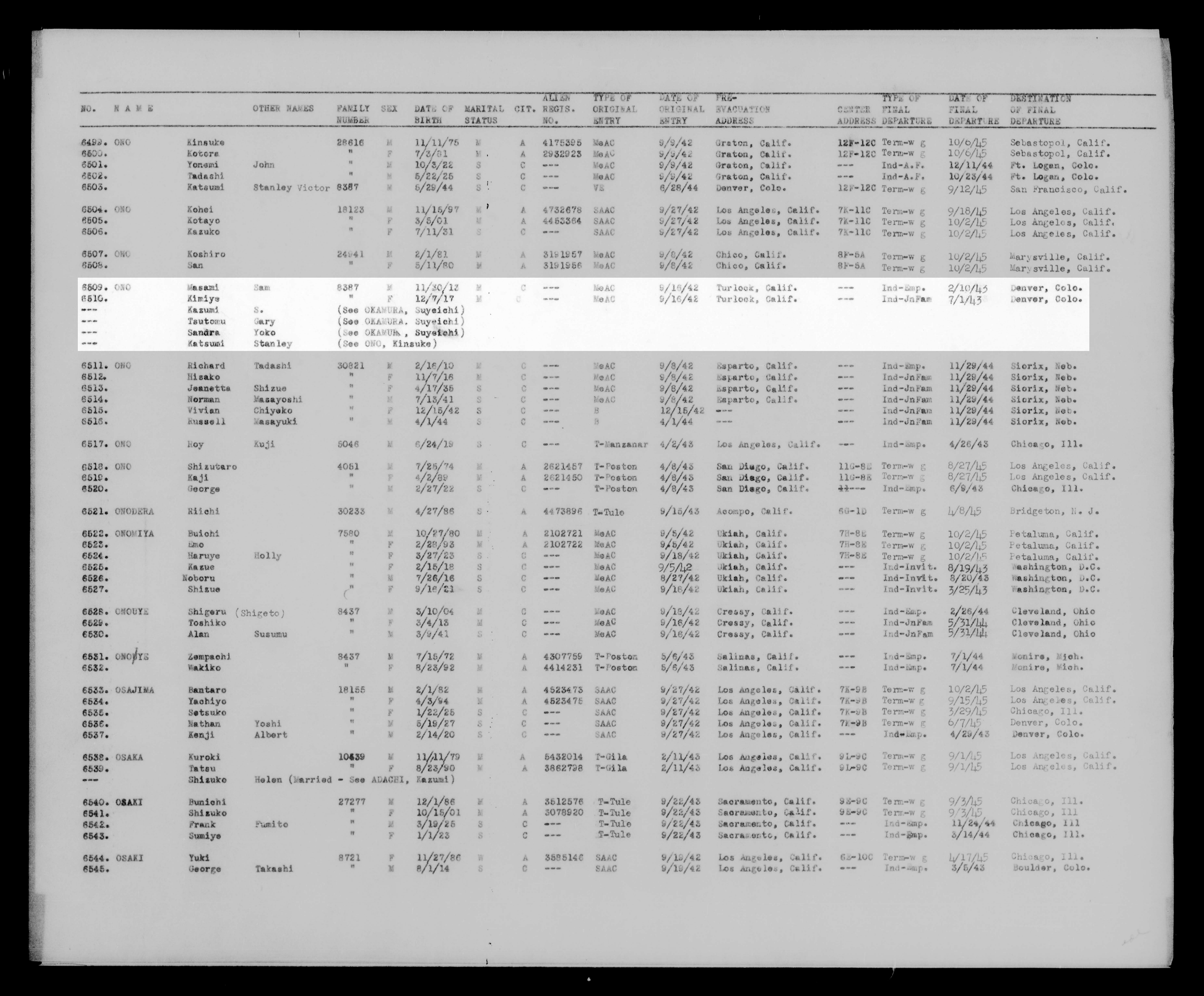

Gary’s information as it appears in the Final Accountability Roster for Amache. Courtesy of Densho Encyclopedia.

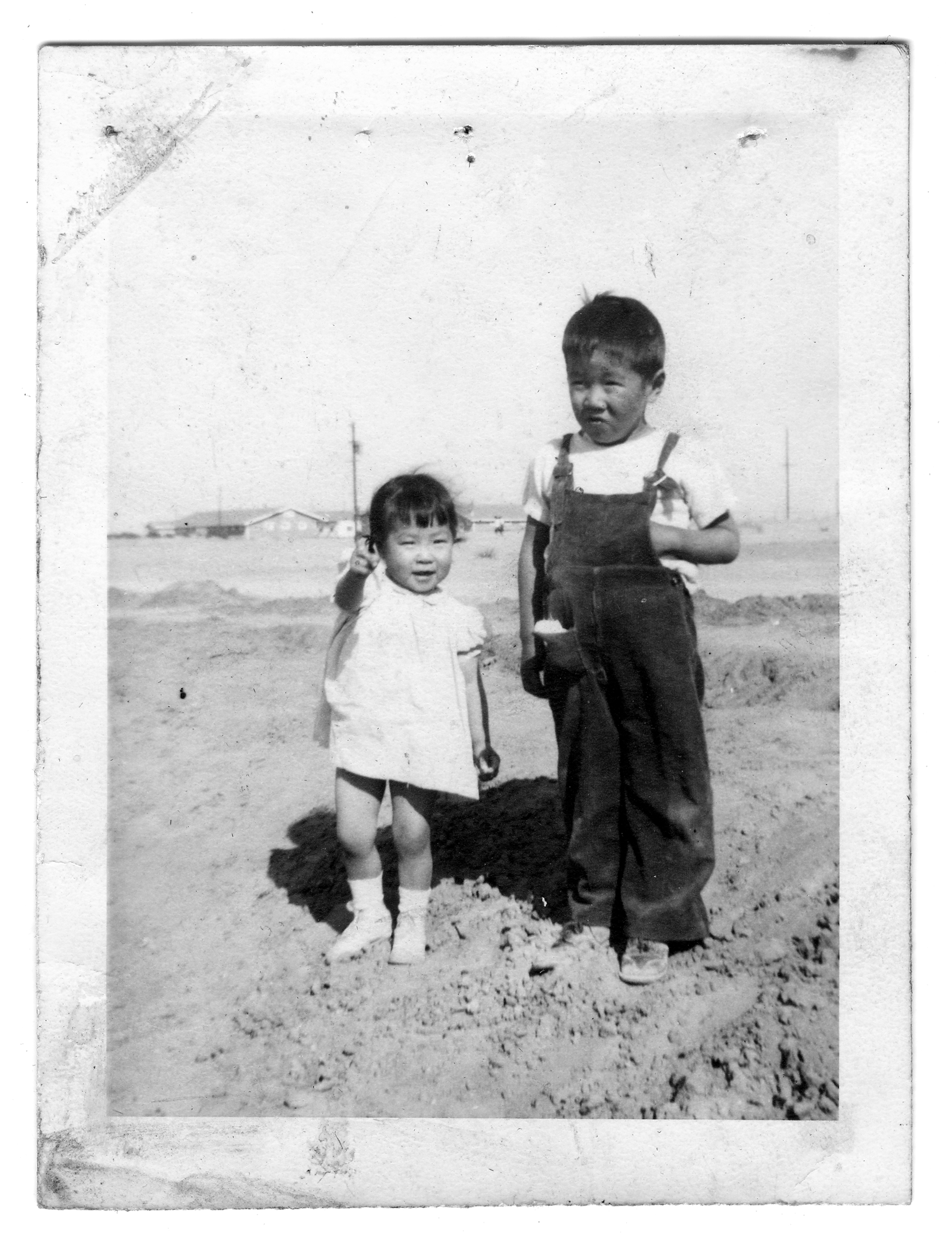

Gary (second from left) at Amache with his cousin Yae Okamura (left); his sister, Sandra Yoko Ono (middle); his brother, Stanley Kazumi Ono (second from right); and another child from Block 10E. Courtesy of the Ono Family Collection.

Listen to this portrait.

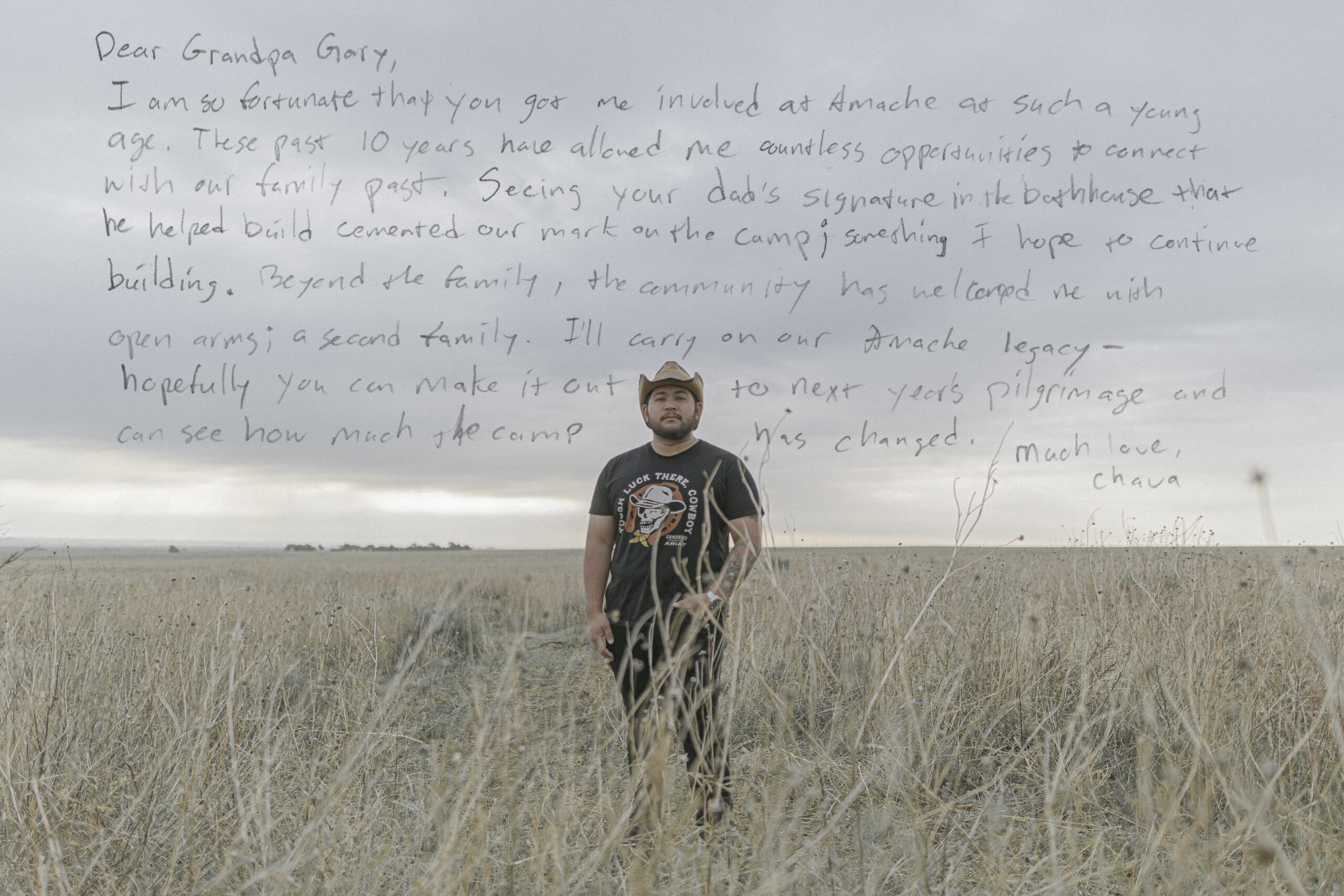

Salvador Valdez-Ono

Gosei

Salvador Valdez-Ono is the maternal grandson of Gary T. Ono. He was born in Ukiah, CA to a Japanese American mother and a Mexican American father.

Growing up, Salvador says he didn’t feel a strong connection to any specific cultural identity. “I grew up in a 90% plus white city, so for me, I didn’t really have a Japanese or a Mexican community,” he explains. “My mom—my granddad, too—we’re all pretty culturally white American.”

At age 14, Salvador visited Amache for the first time to participate in an archaeological dig at the site. During this visit, his grandfather pointed out his great-grandfather’s signature on a cement block pedestal, likely left there when he was working as part of a volunteer crew helping to build the camp. “It was neat to see that they were there, building the camp as well,” he recalls. “I thought it was funny that they were building it, and I was kind of dismantling it through archaeology.”

In college, Salvador chose to major in anthropology and has since returned to Amache for archaeological research, where he now gives barrack tours of his family’s block. “I think my cultural identity is very different from a lot of folks in that I am more connected to an Amache-specific diaspora than a Japanese American one,” he reflects. “Whenever I do a barrack tour, I get to meet people who were neighbors, or whose parents or grandparents were neighbors. I think that’s when I start to feel like I am part of a community.”