“When [they] came back to Seattle, the renters wouldn’t leave. So my family lived literally a block down the street from their own house in the Japanese language school, which had been set up as a hostel for families returning to Seattle.”

— Erin Shigaki, on her aunt’s return to Seattle after camp

Irene Shikibu Shigaki

Nisei / Sansei

Irene Shikibu Shigaki was born in Seattle, WA to Issei and Nisei parents. When Executive Order 9066 was issued, she and her family were sent to Puyallup Assembly Center before being transferred to Minidoka.

Prior to the incarceration, Irene’s father was college-educated and owned a home in central Seattle. After being incarcerated and forced to give up his professional ambitions, he fell into a depression and refused to work at the low wage jobs offered in camp. Instead, Irene’s mother took on multiple jobs to support their family, one of which included delivering milk formula to the mothers residing in their barrack block. “My aunt remembers being with her mother, dragging the wagon around and delivering these formulas,” says her niece Erin.

Irene’s mother gave birth to her third child while incarcerated in camp. In January 1944, she braved the bitter cold, walking from her barrack to the camp hospital, where her son—Erin’s father—was delivered by a horse veterinarian.

Irene’s family returned home from Minidoka about a month after the war ended. Prior to their incarceration, they had left their home in the care of a friend to rent out to tenants while they were gone. “When [they] came back to Seattle, the renters wouldn’t leave,” says Erin. “So my family lived literally a block down the street from their own house in the Japanese language school, which had been set up as a hostel for families returning to Seattle.” Irene and her family lived in the hostel for the next four months until the tenant decided to return their home to them. “That was a strange, almost torturous thing,” says Erin. “They could see their house if they looked up the street.”

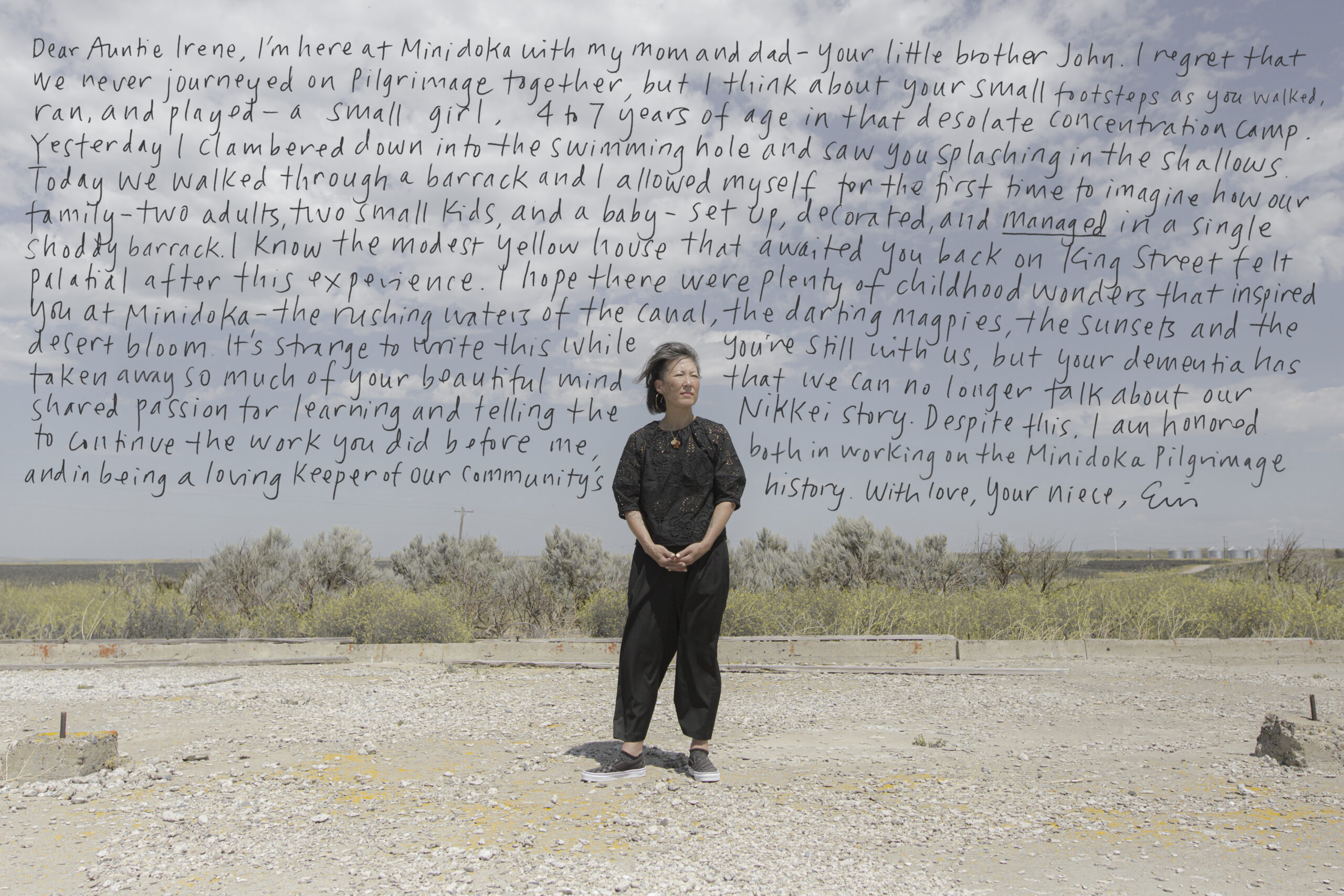

Irene spent the rest of her childhood and early adulthood years in Seattle and moved to New York City in her 20s to become an educator. After retirement, she moved back to Seattle and became an active member of the Minidoka Pilgrimage Planning Committee, an organization that hosts annual pilgrimages to the Minidoka site. Erin carries on her legacy with her work on the committee today.

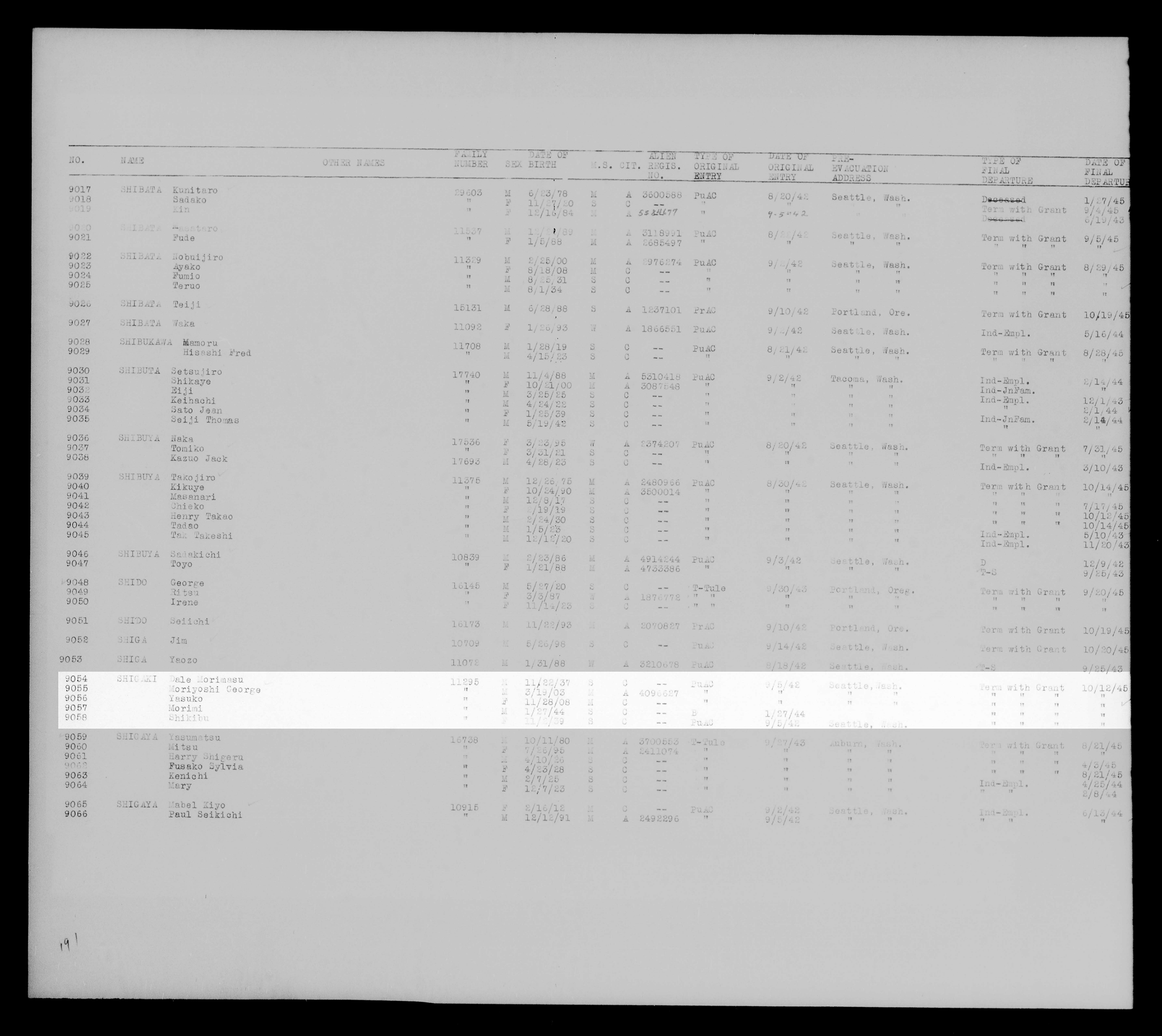

Irene’s information as it appears in the Final Accountability Roster for Minidoka. Courtesy of Densho Encyclopedia.

Listen to this portrait.

Erin Shigaki

Yonsei

Erin Shigaki was born and raised in Seattle, WA. She is the paternal niece of Irene Shikibu Shigaki.

Growing up, Erin learned Japanese at the Japanese language school where her family took refuge after the war. “My grandmother started teaching at the Japanese language school. By the 80s, she was the principal of that school,” she says. “It’s interesting [to see] which people decided we can still embrace our language and culture, even though it was the alleged reason for our imprisonment, our othering.”

Erin has been working as a public artist and community activist since 2018. Aside from her role as Co-Chair of the Minidoka Pilgrimage Planning Committee, Erin is also a member of Tsuru for Solidarity and serves on the board of Look Listen + Learn, a public access television show that inspires and advances early learning in young children of color. Erin says a driving force of her activism is witnessing how the Japanese American community supported each other during and after the war. “The community really took care of the children,” she says. “There was so much anger and depression. But the kids were a priority.”