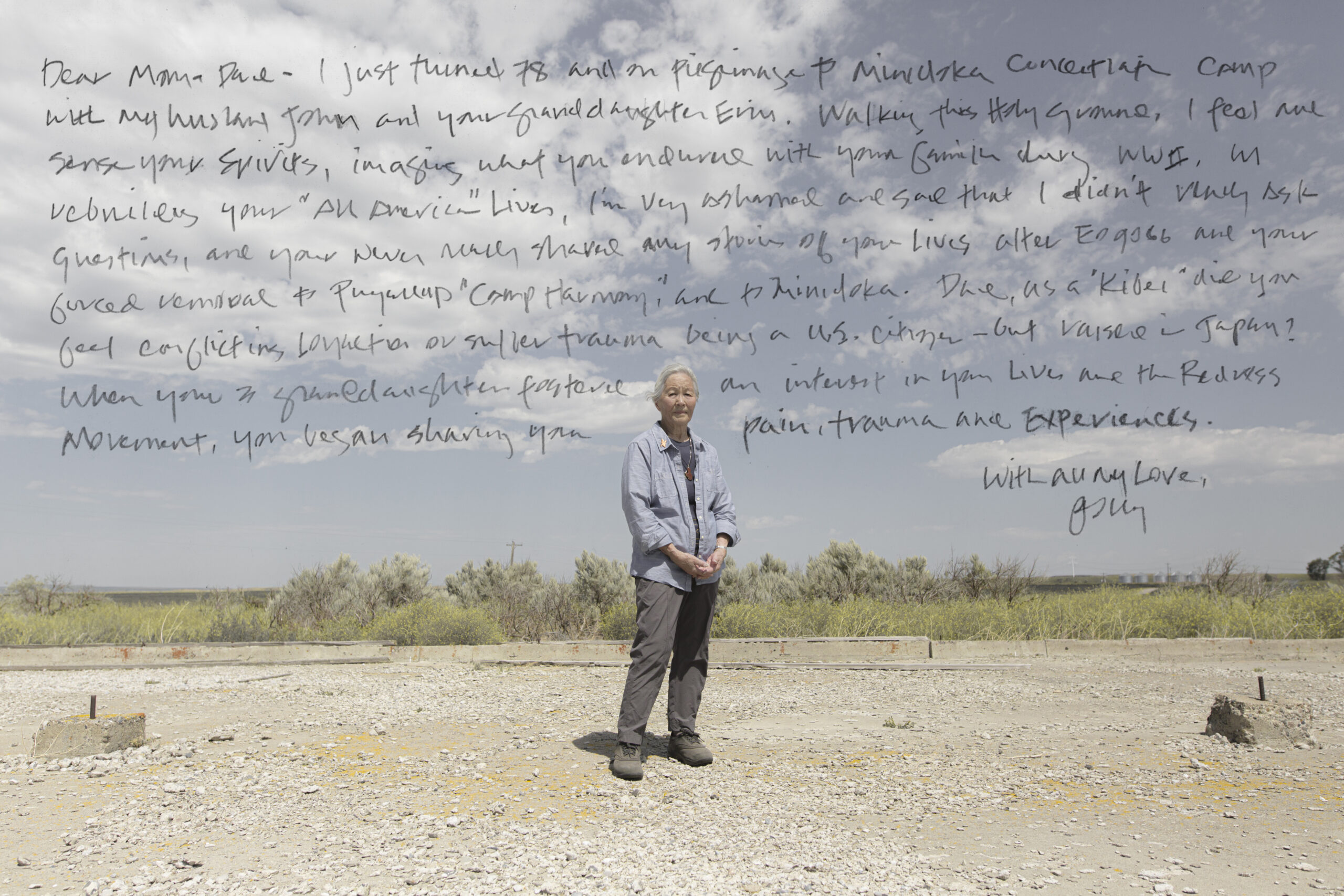

“After the war, he decided he would just cleanse all these things that were Japanese, and maybe that would be easier for me: just being 110% American.”

— Polly Shigaki, on her father

Mitsuko Murakami Otani and Seigo Otani

Nisei / Kibei

Mitsuko Murakami Otani and Seigo Otani met in Minidoka.

Mitsuko was born in Auburn, WA and raised by itinerant farmers in the White River Valley. During high school, Mitsuko moved out to live with a white family and worked as a housemaid to support her parents. “She had to wear this horrible black [maid] uniform with a collar on it,” says her daughter Polly. “It had to be difficult, painful and lonely to live this way. It was just always gaman.” When Mitsuko was 25 years old, Executive Order 9066 was issued and she and her family were sent to Puyallup Assembly Center before being transferred to Minidoka.

Seigo, on the other hand, was born in Seattle and moved to Japan with his family when he was four years old. There, he completed his education and trained as a wagashi maker until he returned to the United States at age 24. “He had elevated taste in classical music and opera,” says Polly. “He really had cultivated high learning for someone of that era.” A few years after his return, Executive Order 9066 was issued and Seigo was sent to Puyallup Assembly Center before being transferred to Minidoka.

Mitsuko and Seigo met a couple years into their incarceration at Minidoka. “They saw each other in the laundry room,” says Polly. “My father was this high tone, high class man […] and my mother was an inaka farm girl.” Despite their starkly different upbringings, they began a courtship. At that point, Seigo had already applied for a Citizen’s Indefinite Leave Card as part of the resettlement program, secured a job in Cleveland and was set to leave Minidoka in a few weeks. Although they’d known each other briefly, Mitsuko agreed to marry Seigo and they left to start a new life together in Cleveland.

The couple initially lived in a hostel in Cleveland while Seigo worked as a baker at a local train station and Mitsuko took on a job as a domestic worker. They eventually welcomed their daughter Polly, and decided to move back home to Washington to raise their family.

They made an effort to give Polly an all-American upbringing, making sure not to speak Japanese or have any Japanese furniture or objects in the house. “[My father] spoke no Japanese, and the only Japanese thing he used […] was an abacus,” Polly says. “After the war, he decided he would just cleanse all these things that were Japanese, and maybe that would be easier for me: just being 110% American.”

Seigo rarely spoke about his incarceration before he passed away in 1987. Mitsuko began to share stories of her incarceration with her grand-daughters in her latter years before she passed away in 2009.

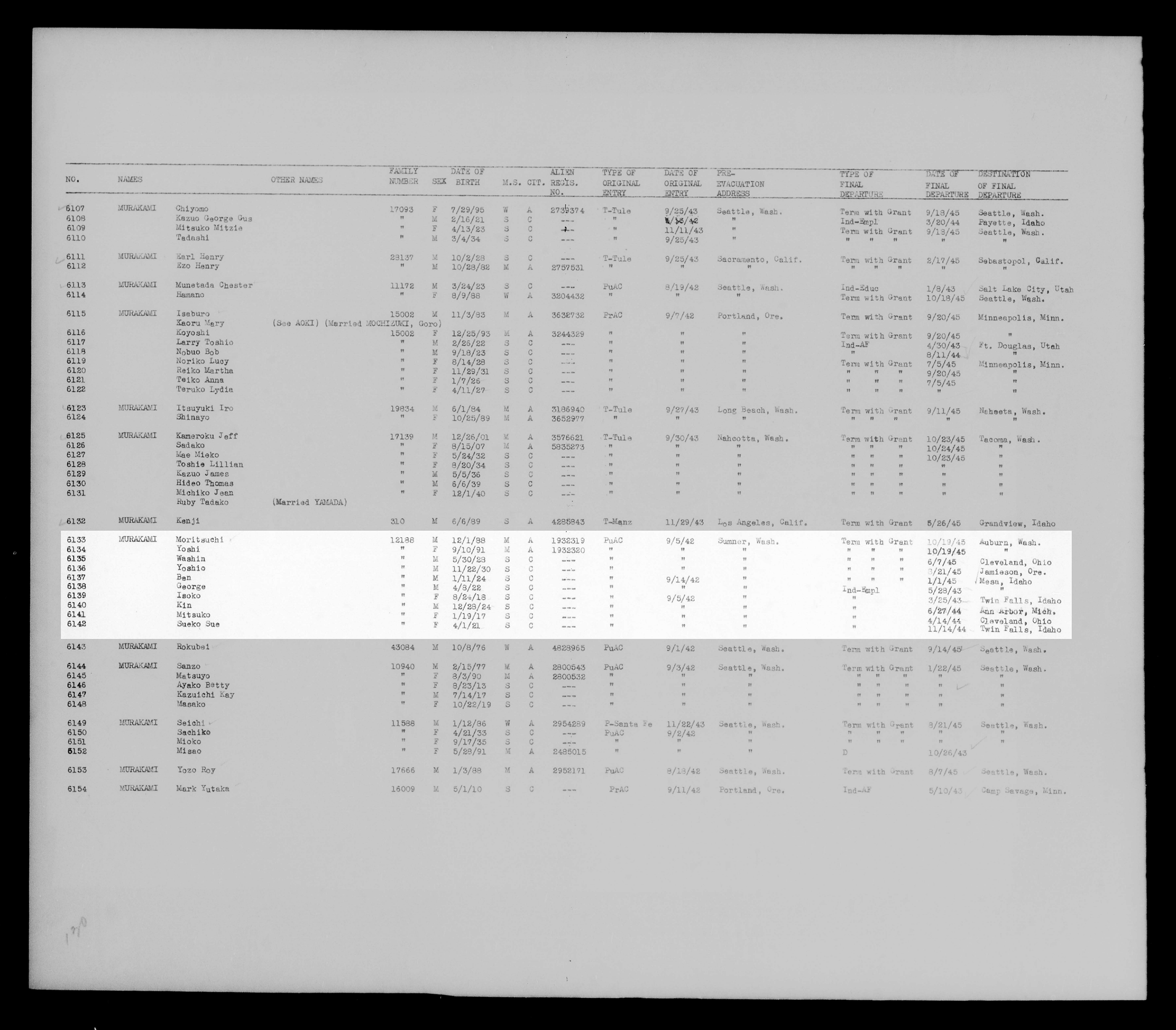

Mitsuko’s information as it appears in the Final Accountability Roster for Minidoka. Courtesy of Densho Encyclopedia.

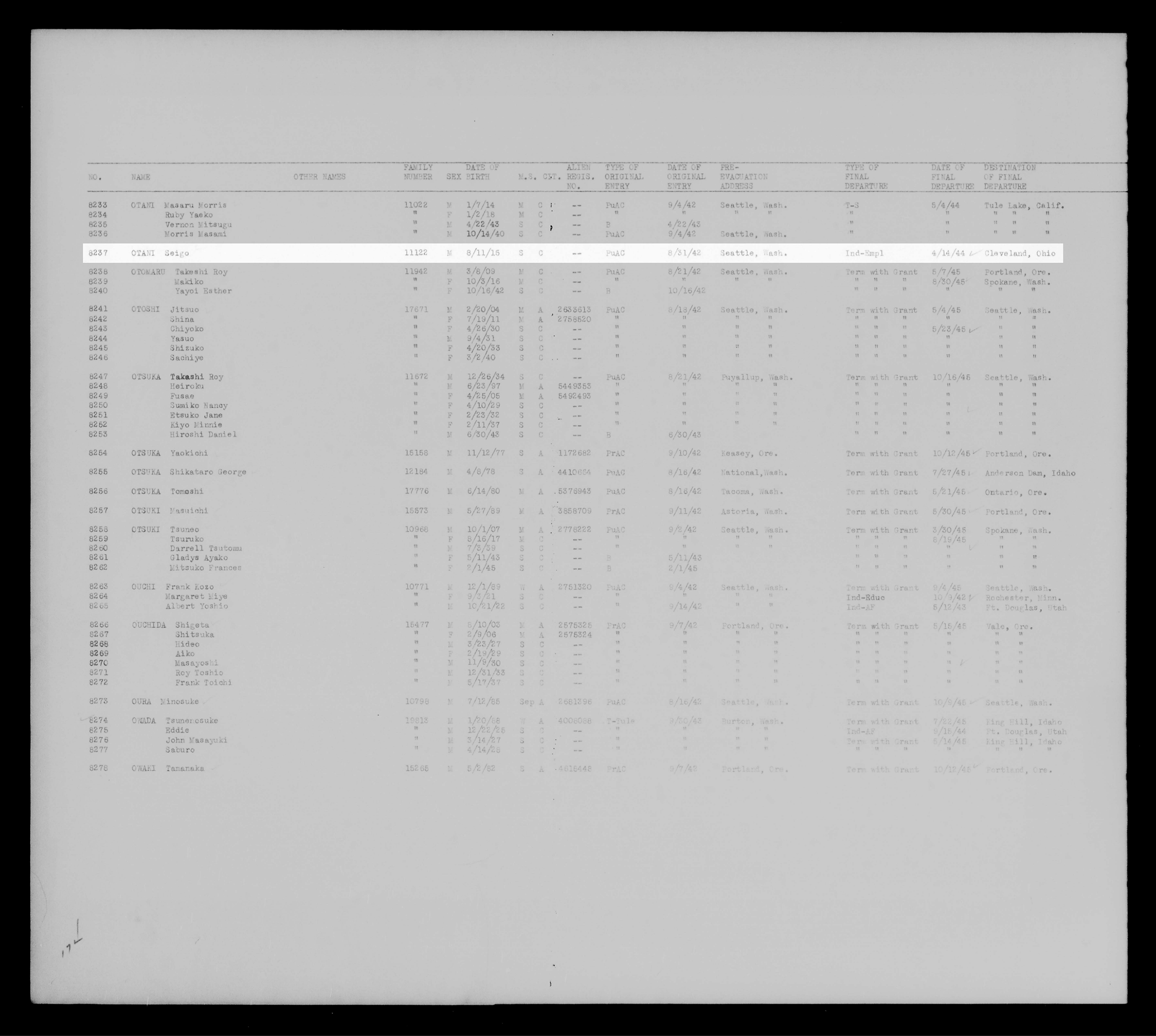

Seigo’s information as it appears in the Final Accountability Roster for Minidoka. Courtesy of Densho Encyclopedia.

Listen to this portrait.

Polly Shigaki

Sansei

Polly Shigaki was born in Cleveland, OH and raised in Seattle, WA. She is the daughter of Mitsuko and Seigo.

Growing up, Polly did not attend Japanese language school. “My dad, in this [effort to] wipe all Japanese things away, said, ‘Oh, she doesn’t need to go to Japanese school,” she says. To learn more about her heritage, Polly decided to take Japanese language classes in college. By the second year, however, Polly noticed that she and her Sansei peers were struggling to keep up with their non-Japanese peers. “[These classes] were filled with PhD candidates and all these really smart hakujin. And all the […] Japanese kids were sitting in the back row trying not to flunk out of class,” she says. “We were ridiculed about how stupid we were as Sansei.”

For a time, Polly lamented the fact that her parents did not take the time to pass their language or heritage down to her. But over the years, she began to see their choices in a different light. “We were so consumed with how to get ahead, getting to a place in life where you’re not struggling all the time,” she says. “I call it a ‘cultural amnesia.’ Silence as a coping mechanism.”

Polly has found ways to honor her heritage through other outlets. After raising her three daughters and running a business with her husband for over three decades, she currently serves as a deacon at St. Peter’s Episcopal Parish, a church that was founded by Japanese Anglican Christians in 1908 and became a refuge for Japanese American incarcerees returning from camp. “St. Peter’s is a historically Japanese American church, where there are now completely different demographics [in the congregation],” she says. “My mission is to try to capture our history, and make sure that no one who comes to St. Peter’s is going to forget it—even if there’s no Japanese Americans left.”