Located in southeastern Arkansas, Rohwer is one of two War Relocation Authority concentration camps in the South. Unlike the other camps that were located in dry and barren settings, Rohwer was situated on 10,161 acres of densely wooded and mosquito-ridden swampland, where a malaria control program had to be implemented in 1943.

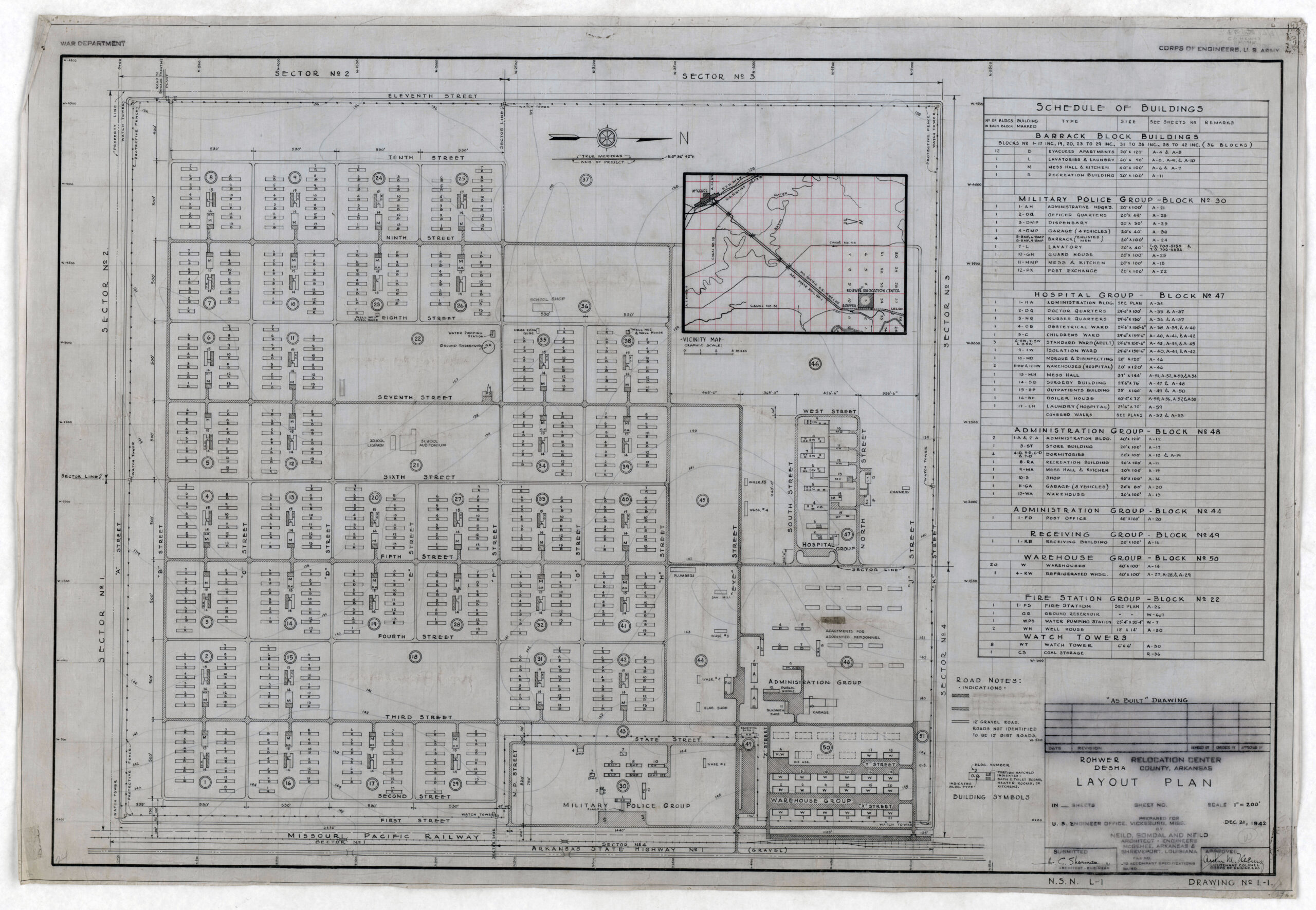

The War Relocation Authority‘s master plot plan for Rohwer. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

Due to persistent drainage problems, the camp grounds were often submerged in swampy water during the rainy season. Incarcerees used wooden walkways to get around camp, which were often slippery and dangerous. Some resorted to tying rope or sacks around their shoes to add traction to their feet. All year round, the camp was swarming with flies, mosquitoes, and biting insects known as “chiggers” that bore into the skin.

Flooded conditions at the Rohwer concentration camp. Circa 1943. Courtesy of Kuroishi Family Collection.

Rohwer concentration camp. May 4, 2023. After its closing on November 30, 1945, the land was auctioned off to local farmers for as little as $5-10 per acre. Currently, much of the land is owned by private farmers.

When the first incarcerees began arriving in the fall of 1942, the camp’s infrastructure was far from complete. Barracks were missing window panes, and entire blocks lacked plumbing and hot water. The mess halls and laundry facilities were unfinished. The water supply was contaminated until the spring of 1943, so incarcerees had to boil their water before drinking it to avoid illness.

Unlike the other camps which were located in dry and barren settings, Rohwer and nearby Jerome were marked by mosquito-ridden swamps and dense vegetation.

The stone monuments and headstones at Rohwer Cemetery are one of the only physical markers of what used to be a populous camp with over 8,000 incarcerees during its peak.

Even though incarcerees were allowed to venture into nearby towns like McGehee, they were met with vocal opposition from some local community leaders.

Some local residents complained that there were “as many Japanese on the streets of McGehee as there have been our citizens,” disregarding the fact that Nisei are U.S.-born citizens.

Early arrivals were tasked with completing the barracks for incoming incarcerees. They installed beds, mattresses, stoves, and light bulbs in the barrack apartments and completed much of the finishing work, such as putting up gypsum wallboards and installing window screens to keep the insects out. During the winter, incarcerees were ordered to cut lumber from the surrounding forests to fuel the wood-burning stoves throughout the camp premises. This task was particularly dangerous for those without lumberjacking experience.

Despite these harsh living conditions, incarcerees found ways to cope. They built porches and overhangs to distinguish their barracks. They tended to individual and communal gardens to beautify the camp. They obtained day passes to visit nearby towns like Dermott and McGehee.

Headstones at Rohwer Cemetery. June 16, 1944. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

Headstones at Rohwer Cemetery. May 4, 2023.

However, the local community’s reception was lukewarm at best. While some residents saw the incarcerees as potential customers, others filed complaints or refused to serve them.

Tensions between the local population and the incarcerees sometimes escalated into violence. On November 10, 1942, a local resident fired a shotgun at a Japanese American private who was on his way to visit his sister in Rohwer. Later that month, a local tenant farmer shot at three Rohwer incarcerees working in the woods outside the camp, claiming that he thought they were trying to escape. In July of 1944, two incarceree truck drivers who were transporting material from the nearby Jerome concentration camp were allegedly attacked by a Desha County sheriff and subsequently jailed. Incidents like these led to growing resentment among the incarcerees, who were already struggling with untenable living conditions and the stress of being uprooted from their homes.

Why is Rohwer significant?

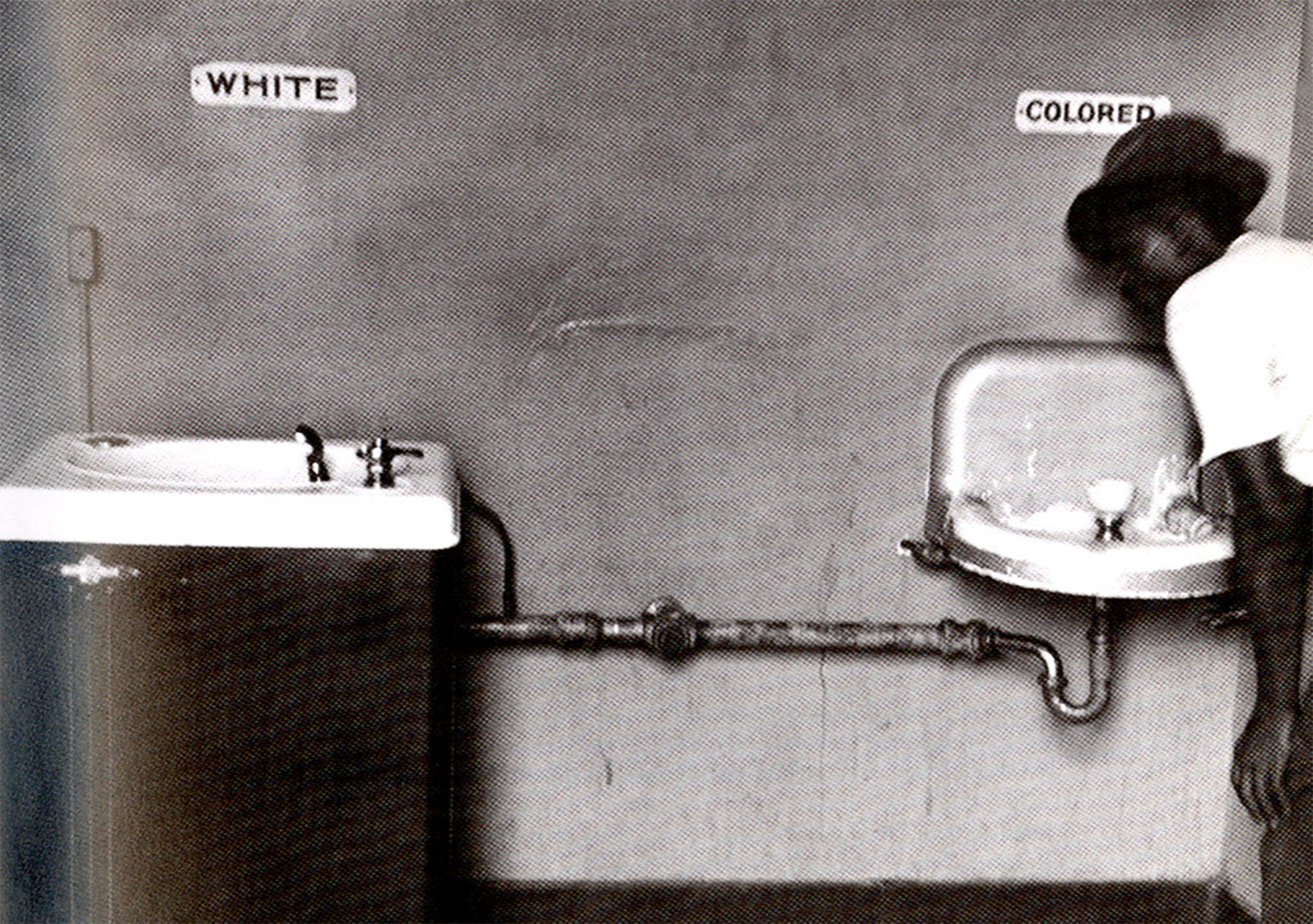

Many of them from California, Rohwer incarcerees recount experiencing Jim Crow laws—like segregated buses and water fountains—for the first time when they visited nearby towns. Circa 1950. Courtesy of the National Museum of American History.

Imprisoned in the South, many Japanese American incarcerees in Rohwer witnessed Jim Crow laws for the first time in their lives. The War Relocation Authority encouraged incarcerees to patron white establishments and limited contact with African Americans, who made up the majority of the local population.

Still, the influx of Japanese Americans in the region inspired vocal opposition from local community leaders, including Governor Homer Atkins, a former K.K.K. member, who introduced five anti-Japanese bills and passed an alien land law targeting Japanese Americans that was later deemed unconstitutional.

Some incarcerees recount being warmly welcomed by Black sharecroppers upon their arrival as they were being escorted into the camp. Many incarcerees struggled to make sense of their incarceration while witnessing the ongoing disenfranchisement of African Americans.