“I feel in my heart that the incarceration defeated him. He took what he could get, and he always presented a very happy kind of face. But he never was able to achieve anything.”

— Joan Okubo Pang, on her father

Listen to this portrait.

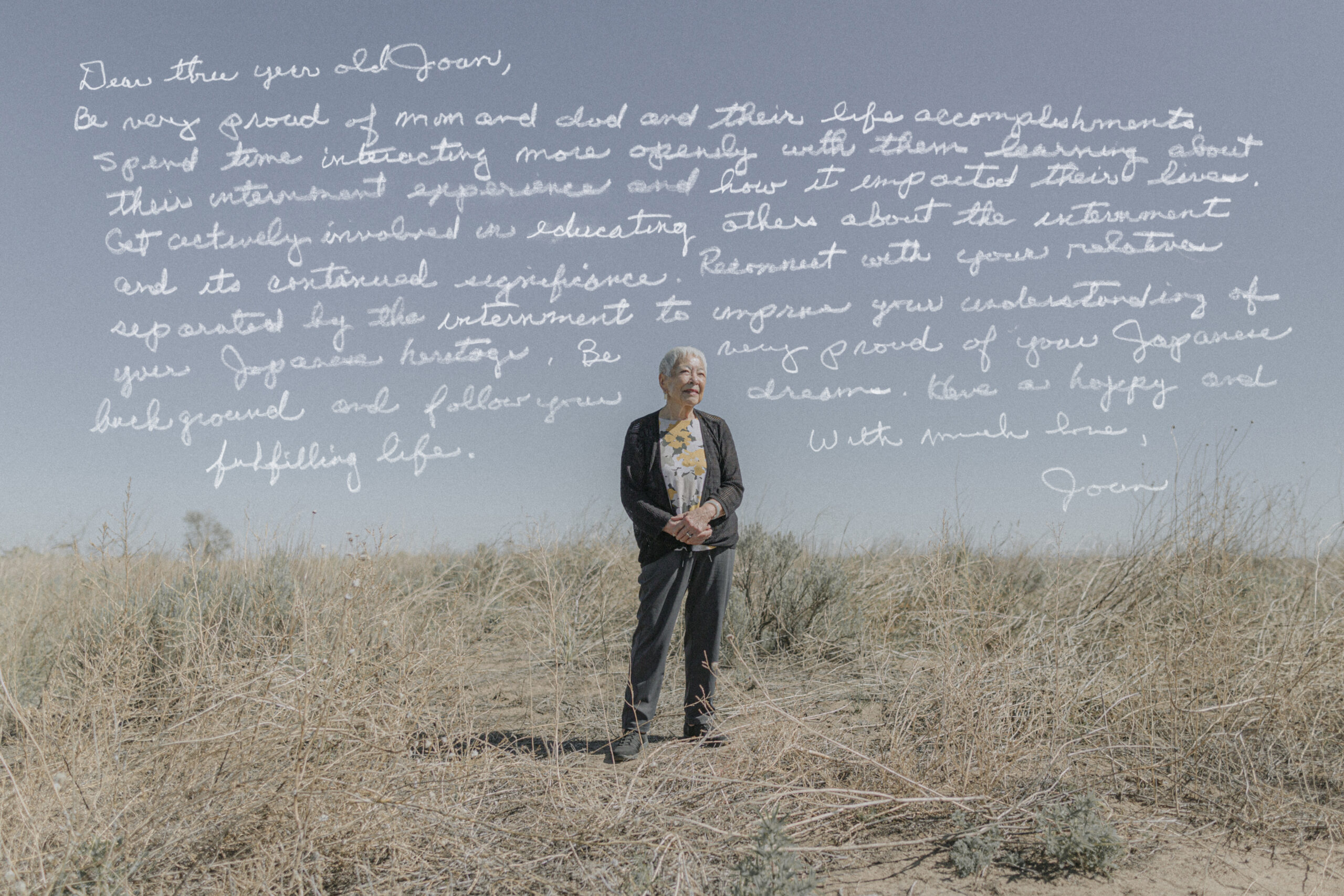

Joan Okubo Pang

Nisei/Sansei

Joan Okubo Pang was born in Los Angeles to an Issei father and Nisei mother. She was three years old when her family was sent to the Santa Anita Assembly Center. “[My mom] talked about Santa Anita as an absolutely horrible place,” she recalls. “It was all hot concrete, and they had one room. They hardly had any furniture, so they had to sit on their cots.” While there, Joan’s mother gave birth to her younger sister, Phyllis. “I always say she was born in a stable, which was true, because they converted the horse stables to a ‘hospital,’” Joan explains.

Four months later, the family was transferred to Amache. Although Joan has limited memories of her time there, she recalls the tough weather conditions. “There was a lot of sand and a lot of wind blowing and tumbleweed,” she says. “But I don’t remember it necessarily as a negative thing. […] Obviously my parents made it tolerable, because it wasn’t registered in my mind as a negative experience.”

After nearly two years at Amache, Joan’s father found work as a caretaker for an estate in Arlington Heights, IL through the U.S. government’s resettlement program. With no home to return to in Los Angeles, Joan’s family decided to move to the Midwest to start a new life.

Before the war, Joan’s father was a successful entrepreneur, running an import-export business. After his incarceration, however, he took on cleaning and maintenance work at the estate, eventually working his way up over the next seven years to manage a chicken farm on the property. “I feel in my heart that the incarceration defeated him,” Joan says. “He took what he could get, and he always presented a very happy kind of face. But he never was able to achieve anything.” Eventually, her family saved enough to buy a house in Mundelein, IL. “My mother always said they were so fortunate that they met a banker who was willing to take the risk with them,” Joan adds.

“The very sad thing about my parents is that they talked very little about that whole period of their life to their kids,” Joan reflects. “I think that they had a shame that somehow they weren’t worthy for many years. And so they wanted us to be integrated into the American life.” After the war, her parents stopped speaking their native language. “They both spoke Japanese,” she says, “I know not a word.”

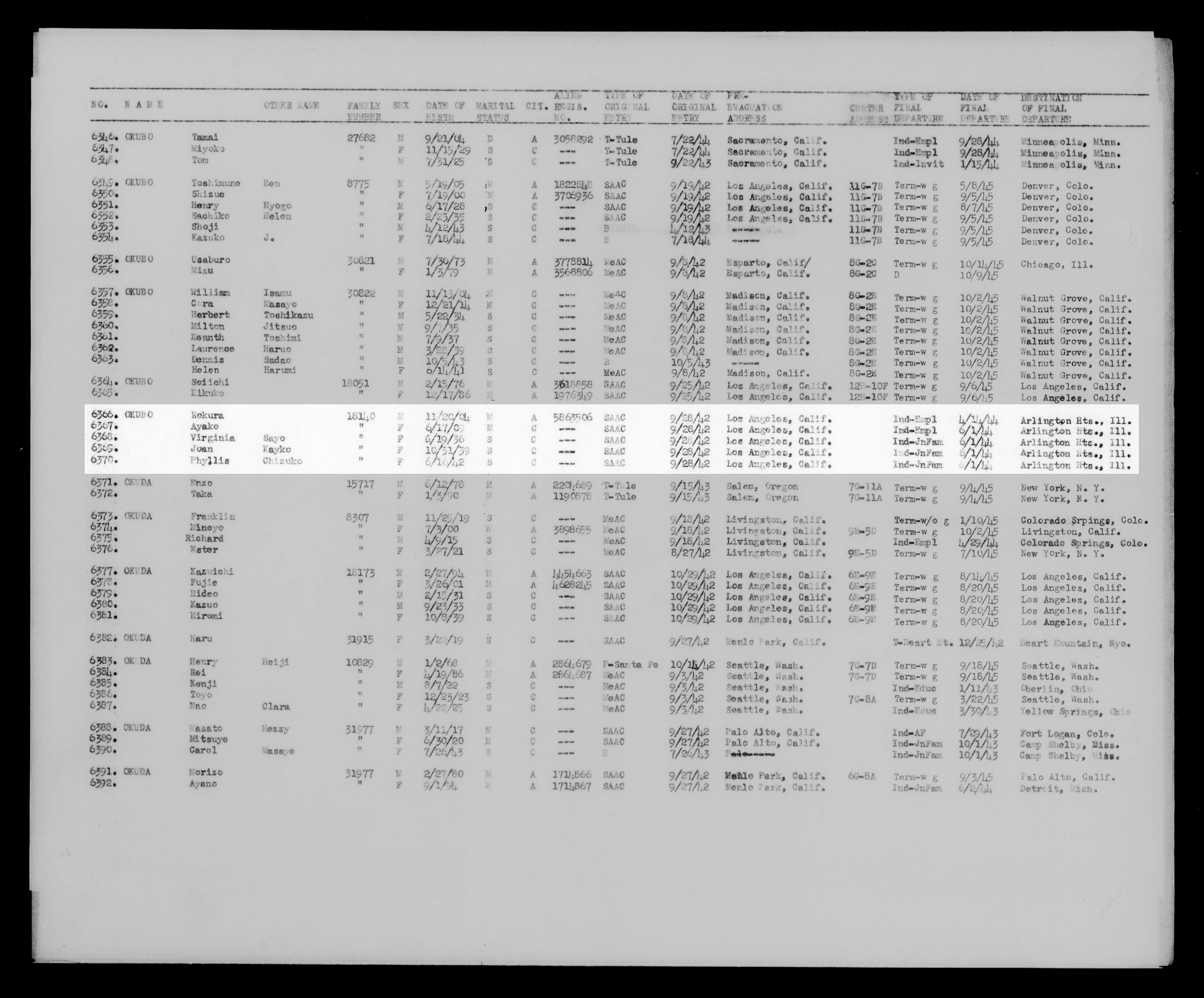

Joan’s information as it appears in the Final Accountability Roster for Amache. Courtesy of Densho Encyclopedia.

From left to right: Joan, her older sister Virginia and her younger sister Phyllis in front of their barrack at Amache. Courtesy of the Okubo Family Collection.

From left to right: Phyllis, Virginia, Joan’s mother Ayako, Joan and Joan’s father Rokuro at Amache. Courtesy of the Okubo Family Collection.

Listen to this portrait.

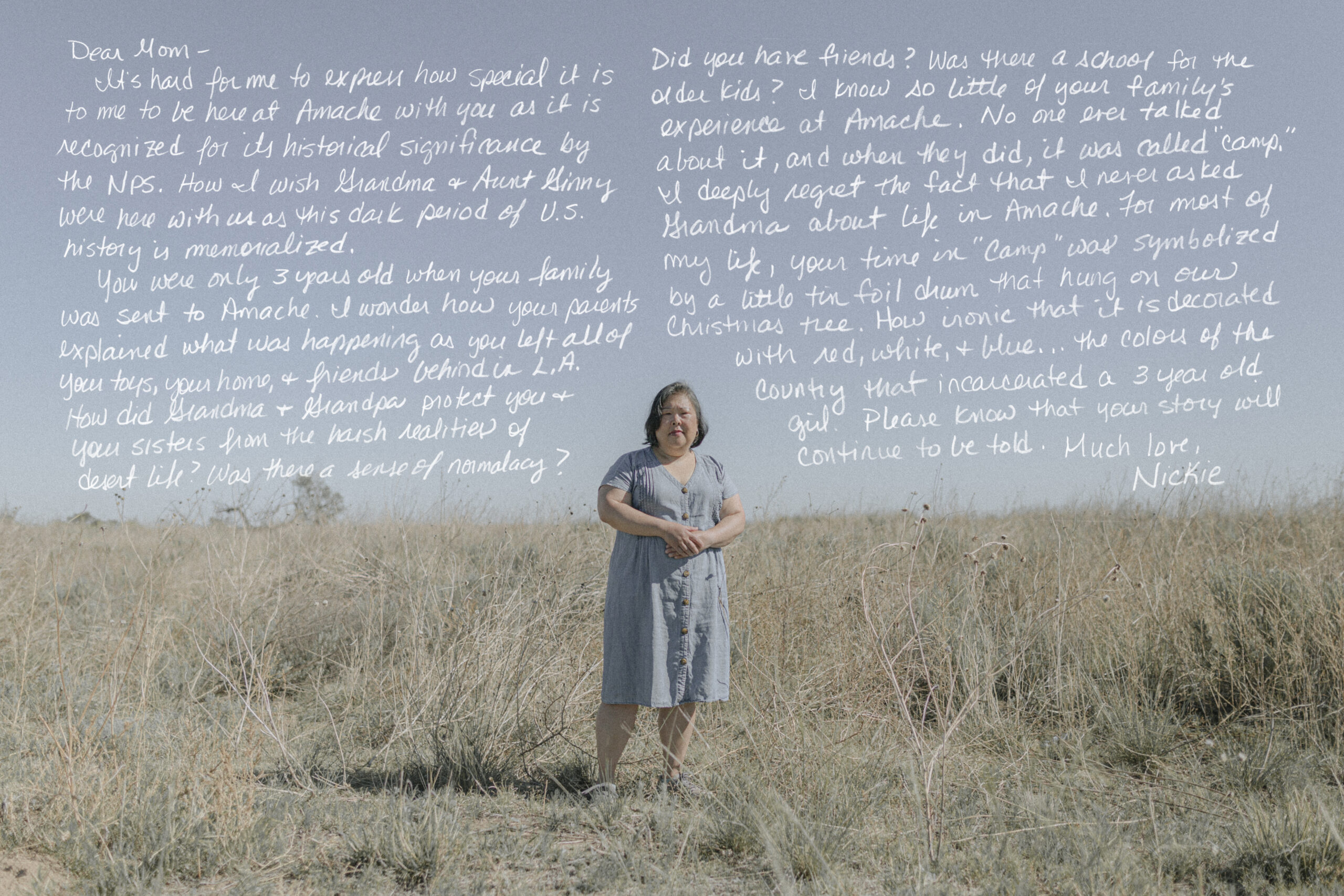

Nicole Pang

Sansei/Yonsei

Nicole Pang is the daughter of Joan Okubo Pang. She was born in Milwaukee, WI to a Japanese American mother and a Chinese American father.

Growing up, Nicole says she didn’t feel a strong connection to her Japanese or Chinese heritage. “I was always very shy—I never wanted anybody to notice me, and I think a lot of that had to do with not understanding my heritage and culture,” she says. “I remember I used to pray every night that I would wake up with blond hair.”

Yet, the word “camp” was present, especially during Christmas. “We have these Christmas ornaments that are little drums, and it looks like a Vienna sausage can wrapped in tin foil […] with red, white, and blue strings along the sides,” she says. “I know that was always one of my mom’s most treasured possessions. She always said, ‘We made it in camp.’ My brother and I always thought they meant summer camp, not knowing any better.”

That changed when Nicole learned about the true nature of “camp” in history class. “I remember saying to [my mother], ‘Did you know that we had concentration camps in the United States?’ And she said, ‘Yes, I was in one.’ I remember just being shocked,” she says. Later, Nicole found photos of her grandmother in the National Archives. “I remember being so excited,” she says. “I showed my mom and she just didn’t react at all. She was angry, and I didn’t understand why.” Nicole eventually discovered that the photos of her grandmother were staged images taken by the War Relocation Authority to promote the resettlement program. “I realized that the photographer was sent out after we got out to show how we assimilated,” she says. “Everybody was supposed to be happy.”

Nicole and her mother had previously visited Amache on detours during longer road trips. However, it wasn’t until Nicole read about Amache’s designation as a National Historic Site in 2023 that she decided to invite her mother to join a pilgrimage. “I think it’s very important for our family history, and the history of our country as well,” she says. “This is something that’s never been talked about much. The fact that it’s now a National Park is significant.”