Okayama Family

Heart Mountain

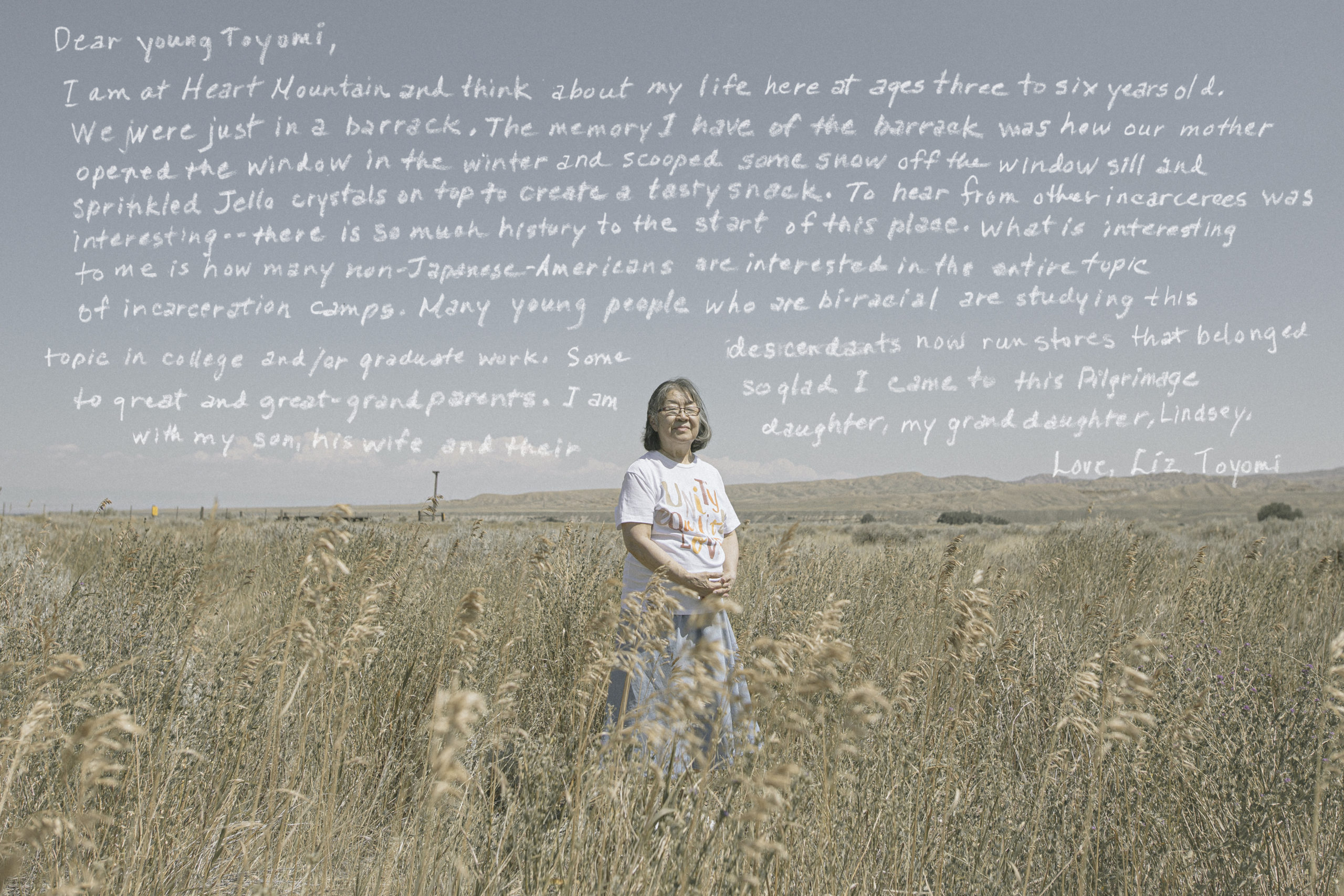

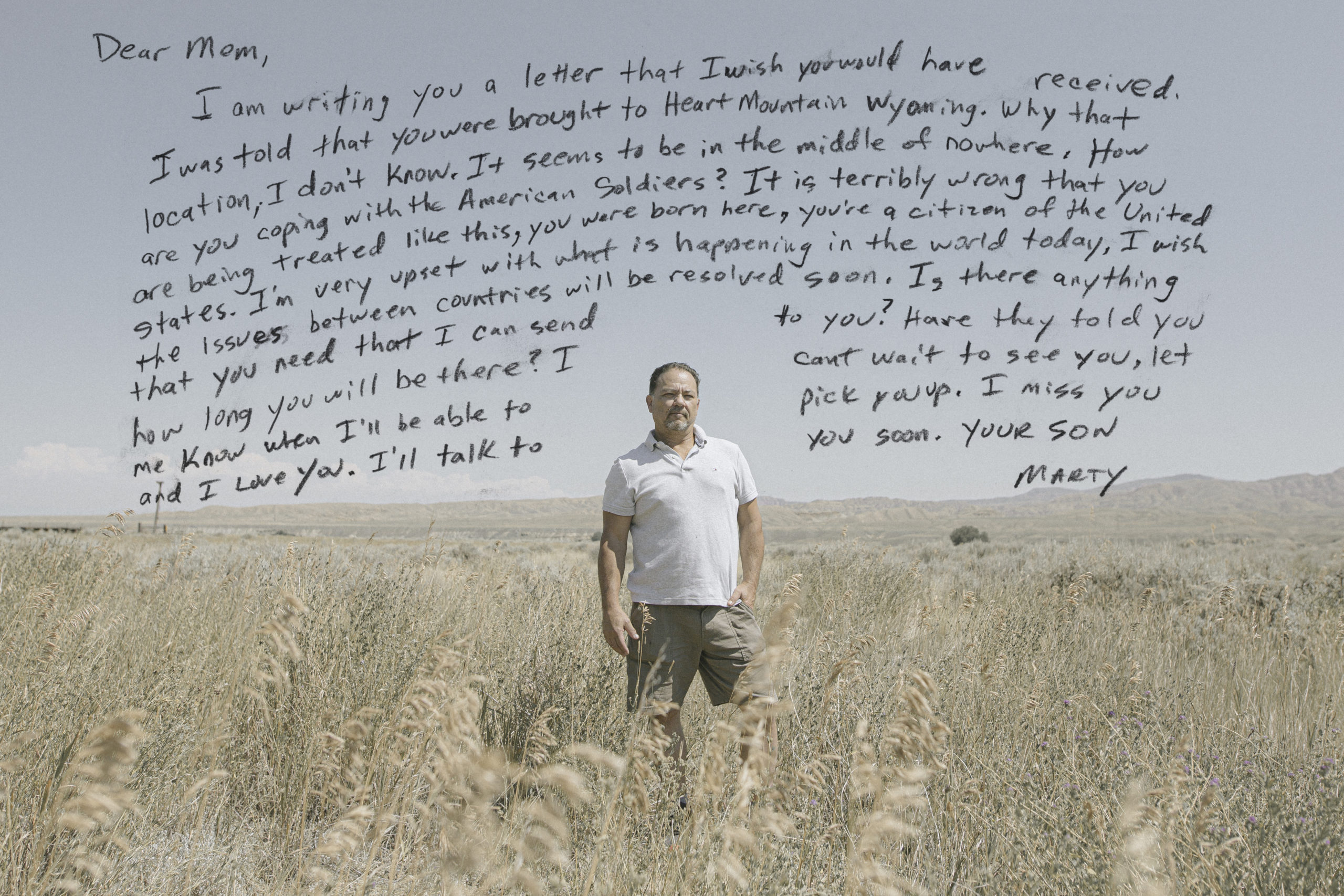

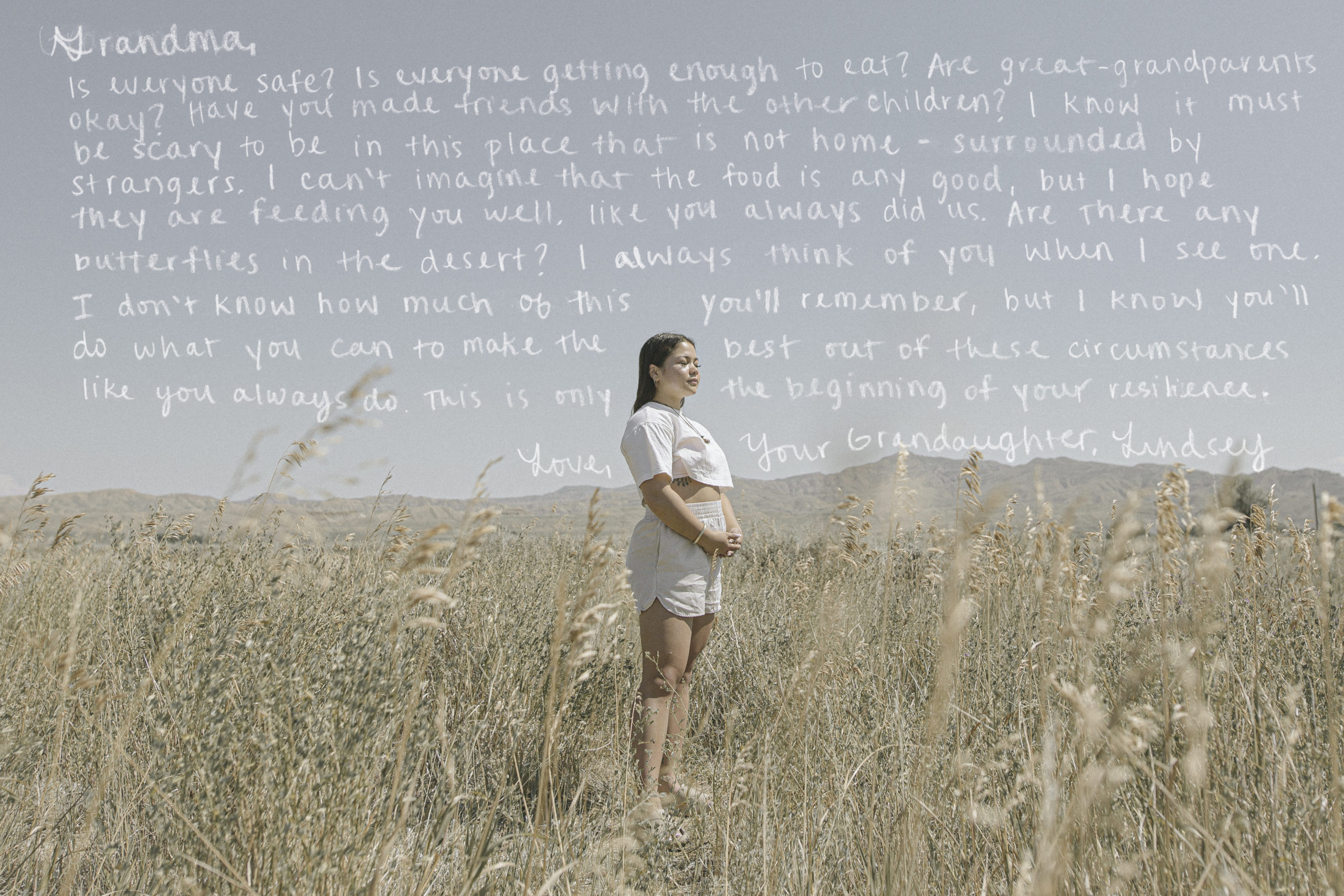

Survivor Elizabeth T. Okayama remembers her incarceration at Heart Mountain with her son Martin Anthony Dopke and her grand-daughter Lindsey Fumiko Dopke.

Survivor Elizabeth T. Okayama remembers her incarceration at Heart Mountain with her son Martin Anthony Dopke and her grand-daughter Lindsey Fumiko Dopke.

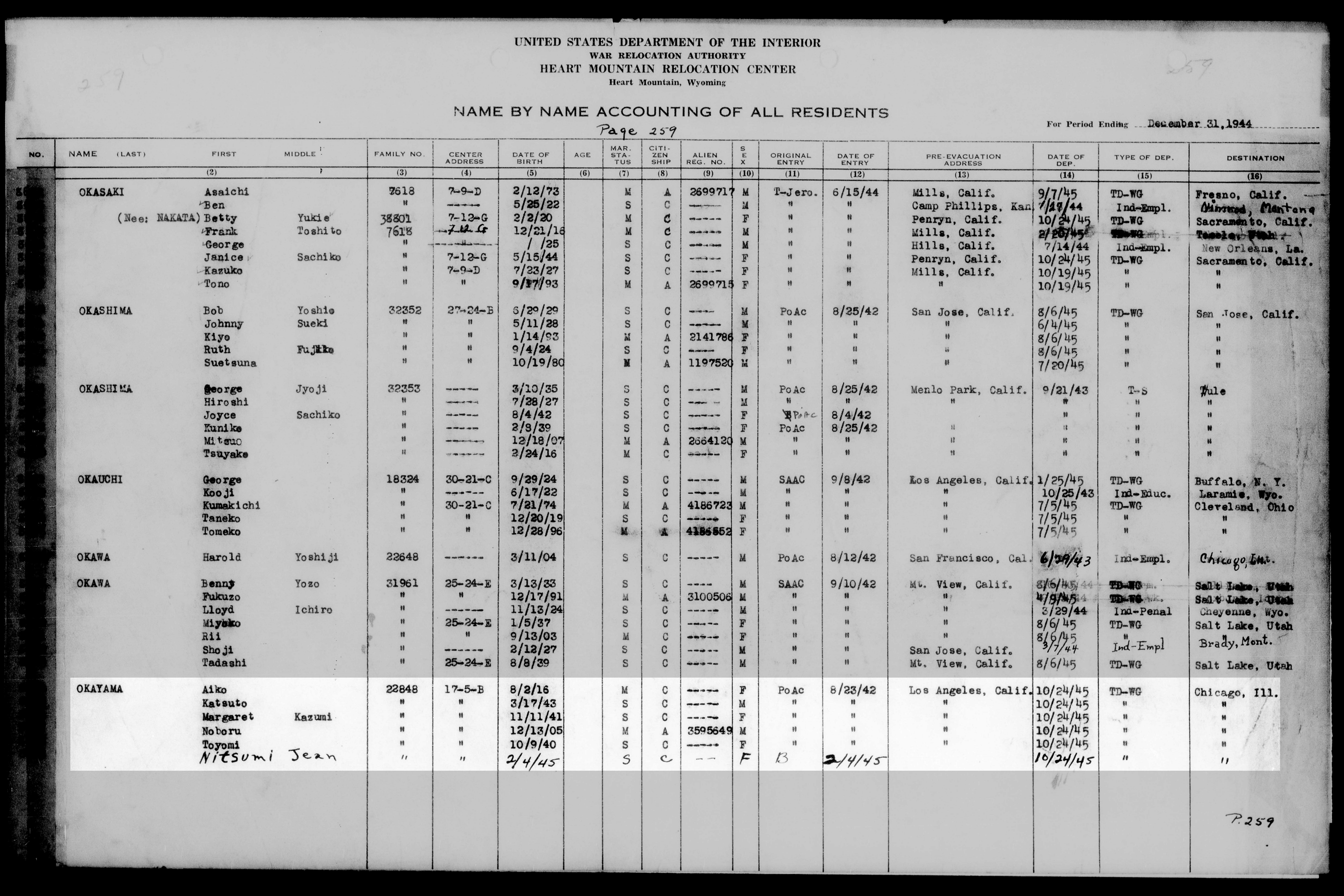

Elizabeth T. Okayama was born in Los Angeles between an Issei father and a Nisei mother.

Elizabeth’s family owned a restaurant where they resided in the attached living quarters. When Executive Order 9066 was issued, they were forced to give up the business and sent to Pomona Assembly Center before they were later transferred to Heart Mountain. Elizabeth was three years old at the time.

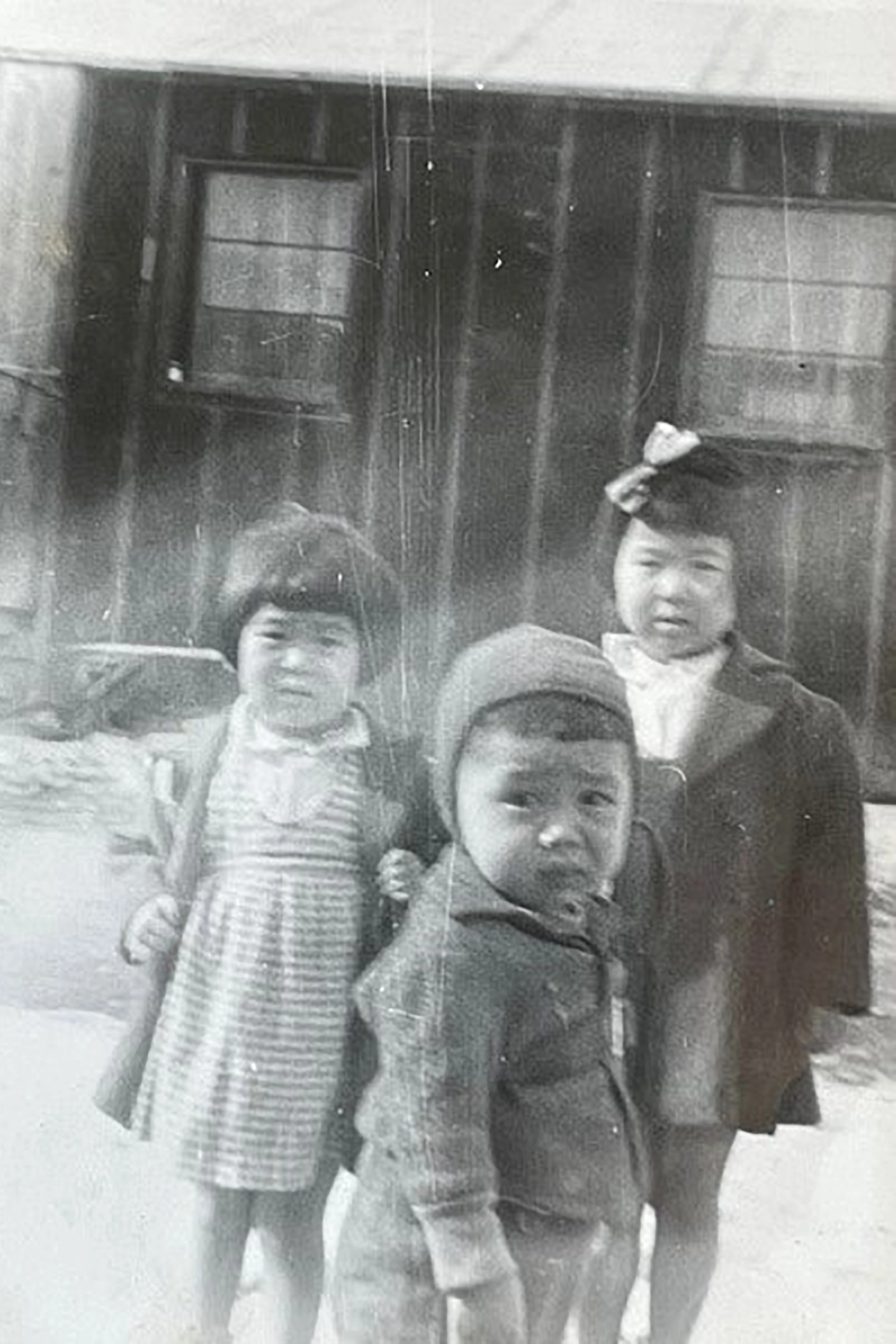

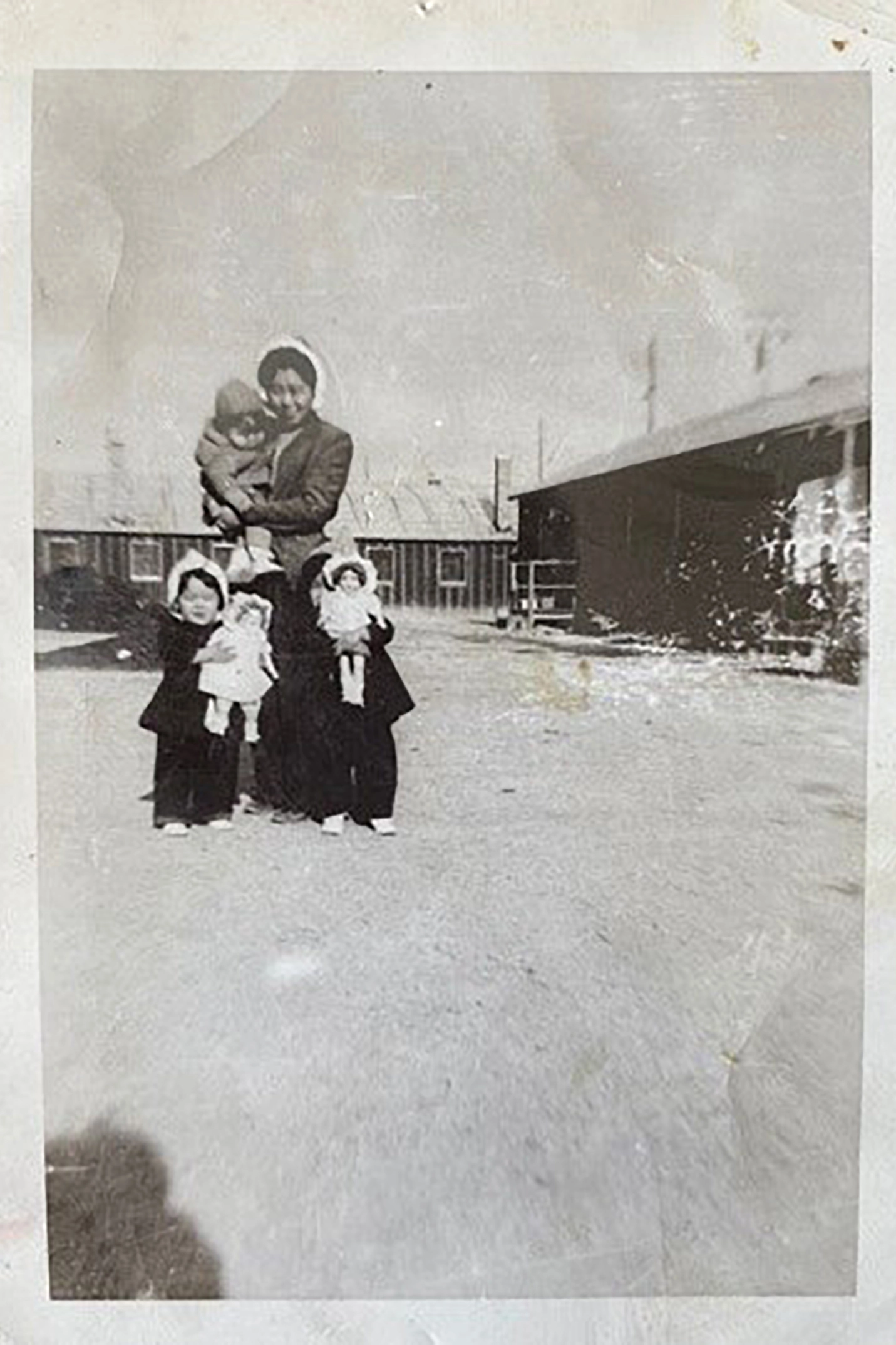

Elizabeth remembers her incarceration only in fragments. “The camp was surrounded by barbed wire,” she says. “There were armed guard towers with guns facing toward the residents.” She also recalls her father working as a cook in the mess hall and her mother bathing her in a large tub in the communal bathrooms.

In small ways, her mother tried to make life comfortable for Elizabeth and her siblings. She carved toys out of scrap wood for her brother to play with. She saved up money to buy American dolls for her sister and her from the camp catalog. In the winters, she sprinkled jello crystals on snow to make a dessert for her children.

After their release, Elizabeth’s father decided not to return to California. “When he went back to look at the place where we lived, he saw, in business windows, signs saying ‘No Japs Allowed’,” Elizabeth says. “My father was determined not to take his family back to that racist environment.” They relocated to Chicago and found an apartment through a friend. “When we moved in, it was dirty. It had dried, dead roaches all along the edge of the woodwork,” she says. “But my mother made it a comfortable place for us to live.” Elizabeth’s family—her parents and four children—lived there with three additional boarders while they got back on their feet.

While Elizabeth’s mother was bilingual, her father only spoke Japanese. Upon entering school after camp, Elizabeth spoke little to no English. Although she was in the first grade, Elizabeth was placed in kindergarten for half of the school day to improve her language skills. “The principal told [my mother] not to speak Japanese to us at home, so that we would learn English,” she says. “What I regret about that is how my mother obeyed the principal.” Elizabeth no longer speaks Japanese.

After settling in Chicago, Elizabeth’s father filed a property loss claim via the Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act for his California restaurant. “He received, I think, $7,000 for the restaurant, house, and everything that was in the restaurant,” Elizabeth says. “I don’t know how he felt about the amount compared to what it actually was worth. But it gave him enough money to start his own business.” Elizabeth’s father used the money to start a wholesale fish business and pursued several other trades including tofu making and selling jars of shrimp cocktails. Eventually, he was able to open a new restaurant in Chicago.

Martin Anthony Dopke was born and raised in Chicago. He is the son of Elizabeth T. Okayama.

Martin says he first learned about the camps from family members when he was about 10 years old. “[I was told] that all the Japanese Americans were rounded up and put into camps,” he says. “But I always had the feeling that everyone was treated well.” Martin recalls hearing about his grandfather’s belief that the camps were meant to protect them from increasing racism and hostility toward Japanese Americans during World War II. “It could have just been what he was telling his family to give them a reason for why they’re there,” he says. “But my grandfather [used to say] that it’s safer for them to be inside the camp than outside of the camp.”

Martin says religion has played a significant role in his family’s healing after the incarceration. “We’ve always gone to church throughout my life,” he says. “I also remember reading the Japanese Seicho no Ie in the bathroom. It’s from my grandmother. She was a Buddhist.” Although his grandmother and mother practiced different religions, Martin wonders if spirituality served a similar purpose in both of their lives. “Forgiveness might be the main way they carried through life. Otherwise, there would be too much hatred and controversy.”

Until recently, Martin was reluctant to visit the camp where his family was incarcerated. “I’ve always avoided it, maybe because the more I think about these camps, the more I will dislike the government,” he says. But his perspective began to change when he witnessed his daughter taking an interest in the camps. When his mother and sister broached the topic of attending a pilgrimage in 2022, he decided to join. “I’m older now. I can visit and learn about all this without dislike or hatred,” he says.

Lindsey Fumiko Dopke was born and raised in Chicago. She is the paternal grand-daughter of Elizabeth T. Okayama.

Born between a mixed heritage Japanese and European father and a mixed heritage Japanese and Black mother, Lindsey says she did not always feel connected to her Japanese heritage. “When I was in elementary school, I would not even claim my Asian heritage because kids in school would make Asian jokes, like poke fun at it. And I just didn’t want to be associated with that,” she says. “So I would literally walk around telling people that I was half black and half white.”

Lindsey’s perspective began to change when she decided to take a Japanese language class to fulfill a requirement for her major. She says she had taken Latin and French classes up until that point. “I figured, instead of taking something I already knew, I’d try something new, and that was Japanese. I’m so, so happy that I did.”

Lindsey speaks the most Japanese out of her family members. “Out of assimilation, [my grandmother] was forced to learn English, forced to forget Japanese. So that wasn’t carried down,” she says. “I think all the time: [I’m] fourth/fifth generation and out of everyone in my family, I know the most Japanese, which is so crazy for me to think about.”

In the summer of 2022, Lindsey joined the Chicago chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League on a trip to Manzanar. There, she saw carefully preserved rock gardens that were built by the incarcerees. “I understood the idea of shikataganai,” she says. But the rock gardens seemed to be a departure from this commonly held philosophy. “They were almost like a form of peaceful protest,” she says. “Despite being displaced and put in this place that they did not know, they still managed to construct something of their own, still managed to beautify the place in their own way.”