Okamoto Family

Heart Mountain

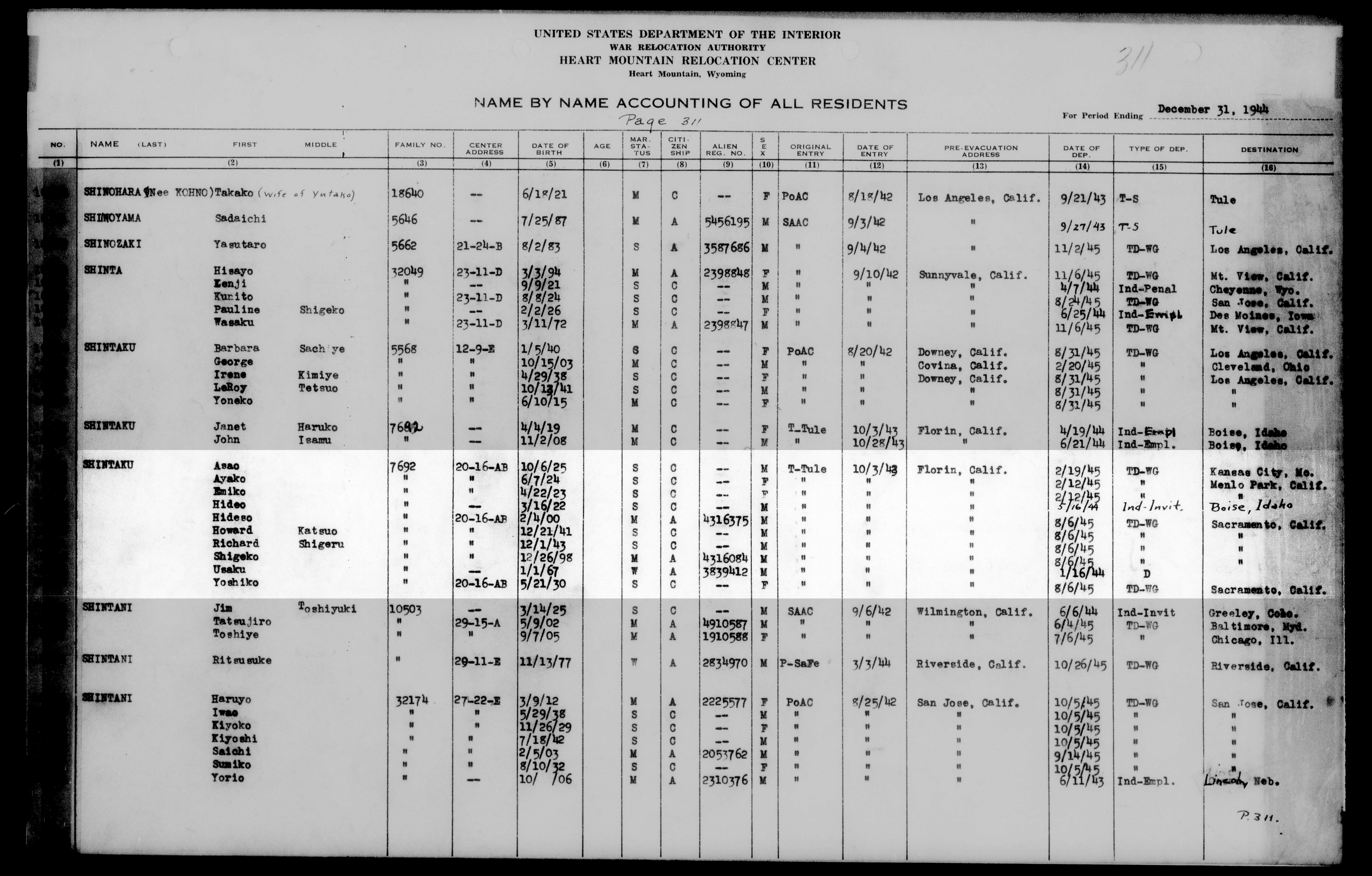

Survivor Yoshiko Josie Shintaku Okamoto remembers her incarceration at Heart Mountain with her children Rodney and Joyce, grandchildren Jason, Ashley and Andrew, and great-grandchild Riley.

Survivor Yoshiko Josie Shintaku Okamoto remembers her incarceration at Heart Mountain with her children Rodney and Joyce, grandchildren Jason, Ashley and Andrew, and great-grandchild Riley.

Yoshiko Josie Shintaku Okamoto—who goes by Josie—was born and raised in Sacramento, CA. Her father died when she was three years old, leaving her mother Shigeko to take up odd jobs to raise her five children. “[Shigeko] was a bootlegger,” Josie’s daughter Joyce says. “She made sake in Sacramento and sold it on wagons with her children. She cleaned the Buddhist church. Unbelievable how she could be a widow of five kids—the youngest three years old—with no social security, no pension, nothing really.” Shigeko later met her stepfather, with whom she had two more children.

Unlike her sisters Ayako and Emiko, Josie did not go by her Japanese name. “Yoshiko maybe was a bit more difficult for a teacher that is a white teacher,” Joyce says. “Her teacher couldn’t pronounce her name, so she started calling her Josie. And it stuck.”

Josie was 11 years old when Executive Order 9066 was issued. Fearing persecution, her family discarded personal belongings that could be traced back to Japan. “They were Imari plates. They would either be buried or given away because you didn’t want to have a lot of ties to Japan,” says Joyce. “[My mother] remembers, unfortunately, destroying pictures.” That summer, Josie’s family was sent to Tule Lake and later transferred to Heart Mountain.

In 1944, Josie’s oldest brother applied for an early release from camp as part of the resettlement program and secured a job at a cannery in Rio Vista, CA. The rest of the family joined them the following year, and they worked at the cannery together before going on to run a bait shop. “My mother’s family did not have a place to come home to,” Joyce says. “But they felt they were lucky that they were coming home to something. They were like, ‘Let’s get this done. We can get a job here. At least we’re all together.”

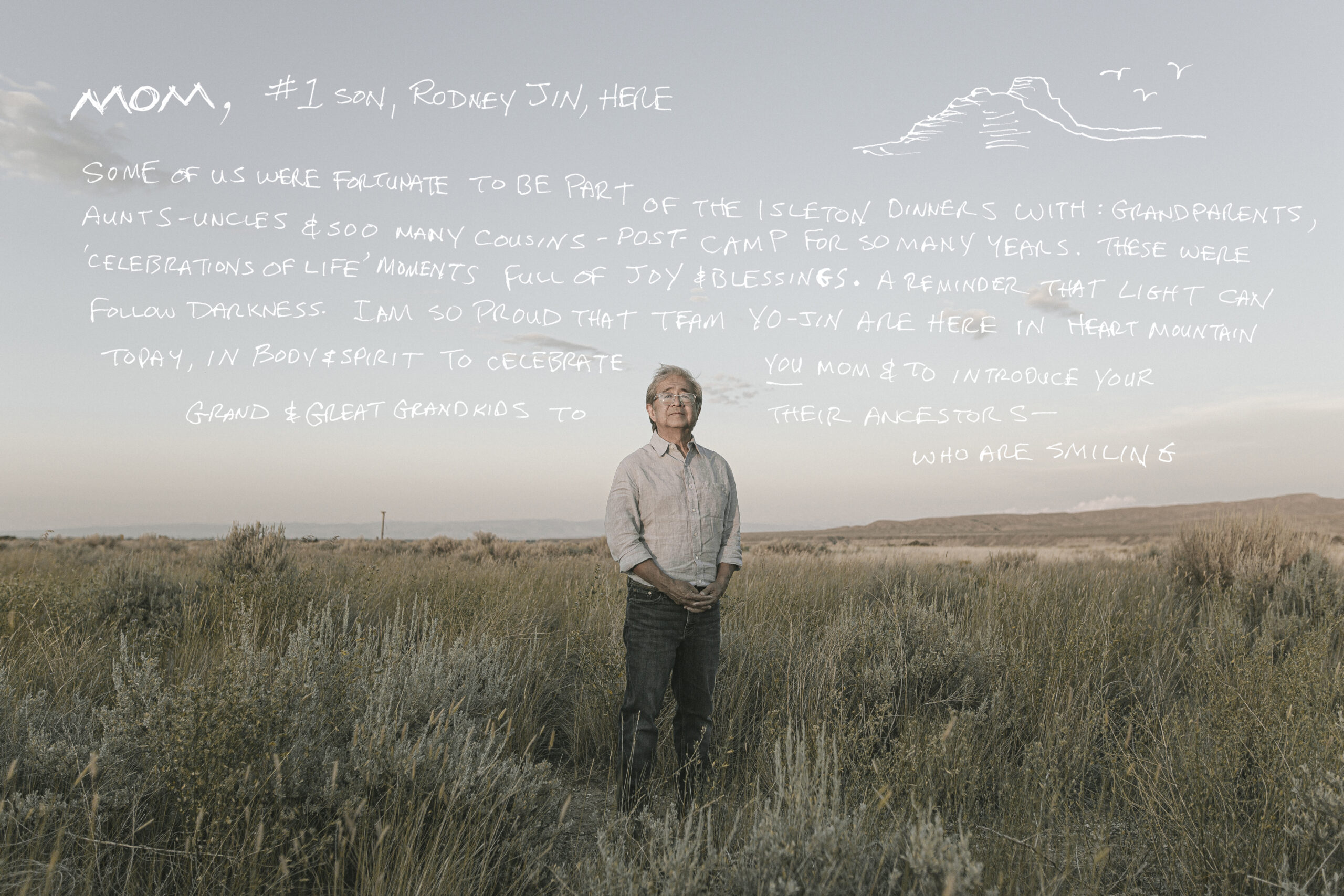

Rodney Okamoto is the son of Yoshiko Josie Shintaku Okamoto. He was born and raised in Lodi, CA.

Rodney and his four siblings were raised on a farm. He spent the majority of his free time helping out on in the fields, and he relished the occasional outing when he and his family would pile into the car and go to the drive-in movie theatre. “I didn’t know we were poor. I just knew we were happy,” he says.

Rodney and his brothers were Boy Scouts and his father was a Scoutmaster. “We never learned Japanese,” he says. “We were just integrated into being American.”

Although both of his parents were incarcerated during the war, Rodney says neither shared many negative experiences about the camps. “They didn’t overdramatize it or dwell on it. It was just something that happened,” he says.

As direct descendants of the incarceration, Rodney says there were certain expectations placed upon Sansei, or people of his generation. “Our parents had everything taken away from them, having to start from zero,” he says. “But all five of us went to college, graduated college. A lot of our Sansei peers did the same thing.” Rodney’s siblings went on to pursue careers in a broad range of industries including advertising, retail and computer sciences, and Rodney started a pharmaceutical company. “The businesses, for 30 years, has been a huge success,” Rodney says. “I’ve made it my message that in one generation, you don’t have to carry stigma from older generations. I’m a true, proud American, because I don’t know that this would have happened even in Japan. I don’t know that we would have succeeded to this extent.”

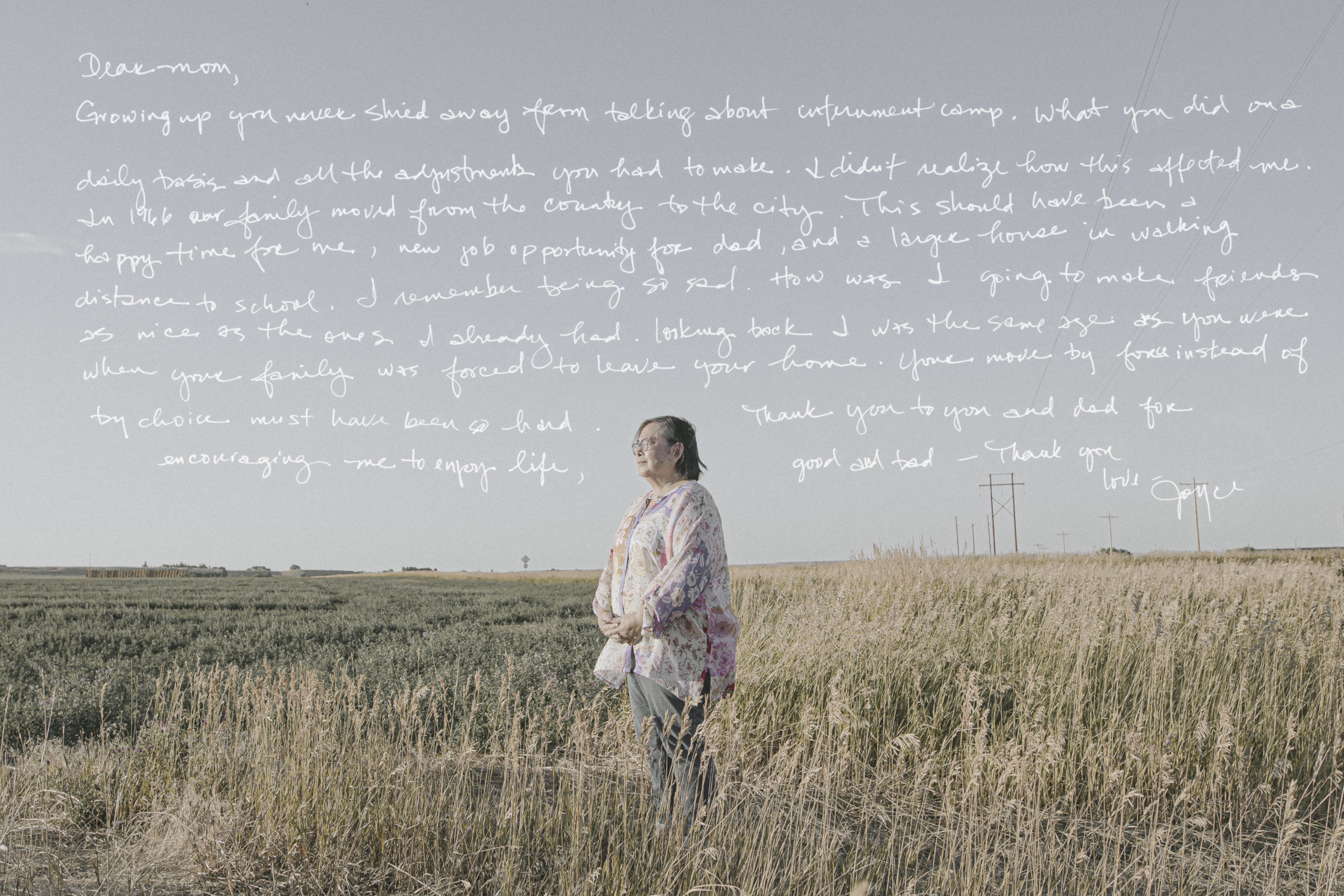

Joyce Pamela Shigeko Okamoto is the daughter of Yoshiko Josie Shintaku Okamoto. She was born and raised in Lodi, CA.

When Joyce was 10 years old, her father contracted tuberculosis and was hospitalized for a year. At this point, her mother Josie had five children—the same number of children her grandmother Shigeko had when she was widowed by her first husband. “We knew my dad was coming back, but he didn’t come back for a year,” Joyce says. “Kind of mimics my grandmother’s life, right?”

At age 11, Joyce’s family decided to move closer to the city of Lodi for a new job opportunity. “I was moving 15, 20 miles to a bigger house, to a better situation, better job for my dad, closer to the schools,” Joyce says. But rather than feeling excited about a new life in the city, Joyce was riddled with remorse for the life she was about to leave behind. While the circumstances were different, Joyce wonders if her anguish was somehow related to Josie’s grief when she was sent to the camps around the same age.

Joyce often reflects on the parallels between the lives of her grandmother’s, mother’s and her own, with all of them facing significant life changes around the same age. “We are very strong women in our family,” she says. “My grandmother was just like, ‘Okay, we’re gonna deal with this.’ Which is like my mother. Which is like me.”

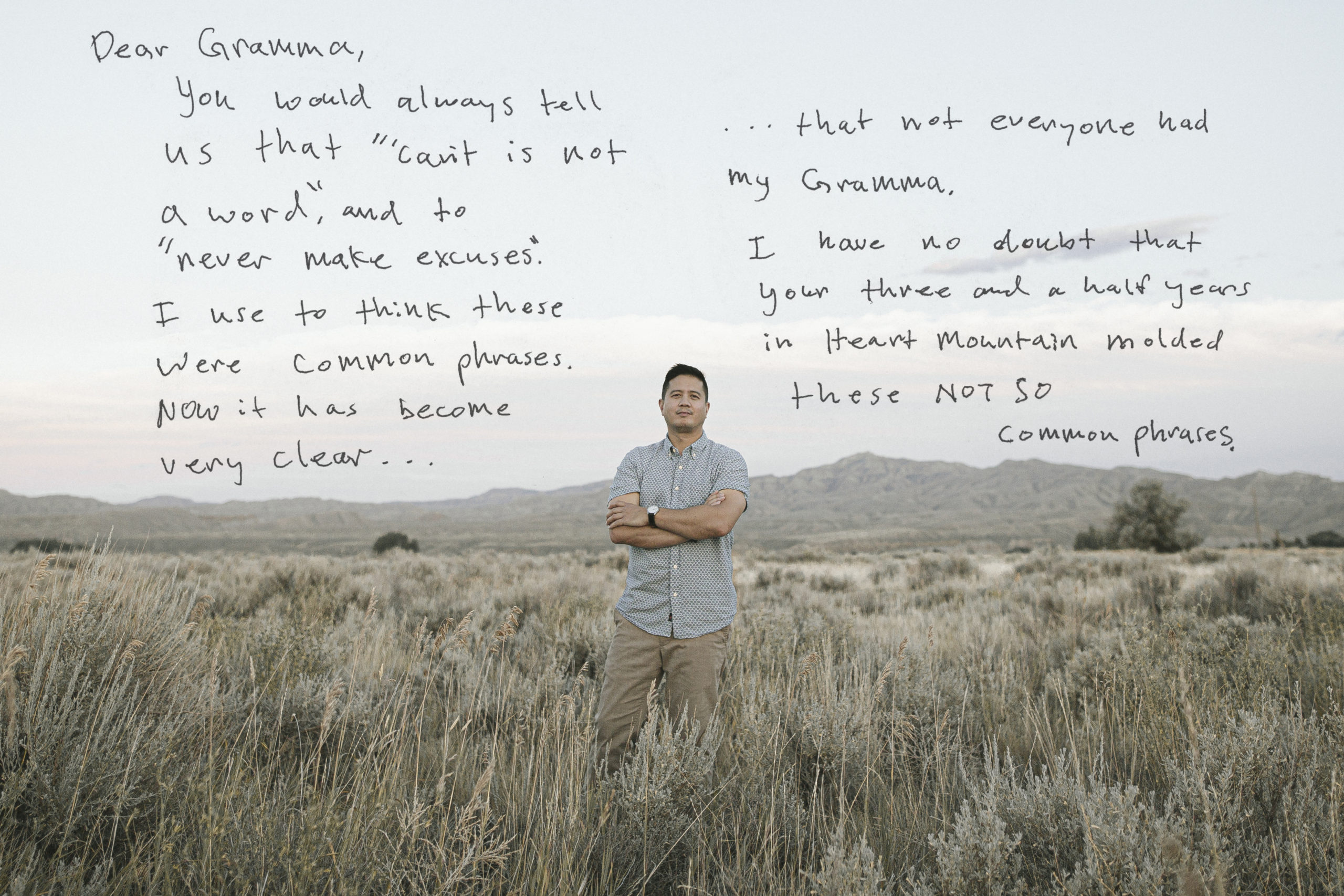

Jason Curtis Okamoto is the paternal grandson of Yoshiko Josie Shintaku Okamoto. He was born in Elk Grove, CA.

Growing up, Jason rarely heard his family speaking about the hardships at camp. “There was an extreme amount of pride to not bring up how hard it was,” he says.

As a mixed heritage Japanese American, Jason says he is reminded of his Japanese heritage whenever he hears Josie recounting memories from her childhood. “You forget that you’re Japanese because you stay with your grandmother and you get doughnuts, you’re going to McDonald’s and diners, stuff like that,” he says. “But then she’ll bring up a memory of something that she did in the Buddhist church, or Obon, or something that her mom made, like a food item or making sake out of a bathtub.”

Jason says Josie instilled in him a sense of pride to be Japanese American. “It’s the idea that we’re more American than other Americans because we chose to stay here. We chose to die for a country that didn’t trust us,” he says. “You can take it two ways: you can say, ‘This is unfair, this sucks, I’m never going to really feel like an American.’ Or you can just lean into it and say, ‘Not only am I American, but I’m more American than all of you.’”

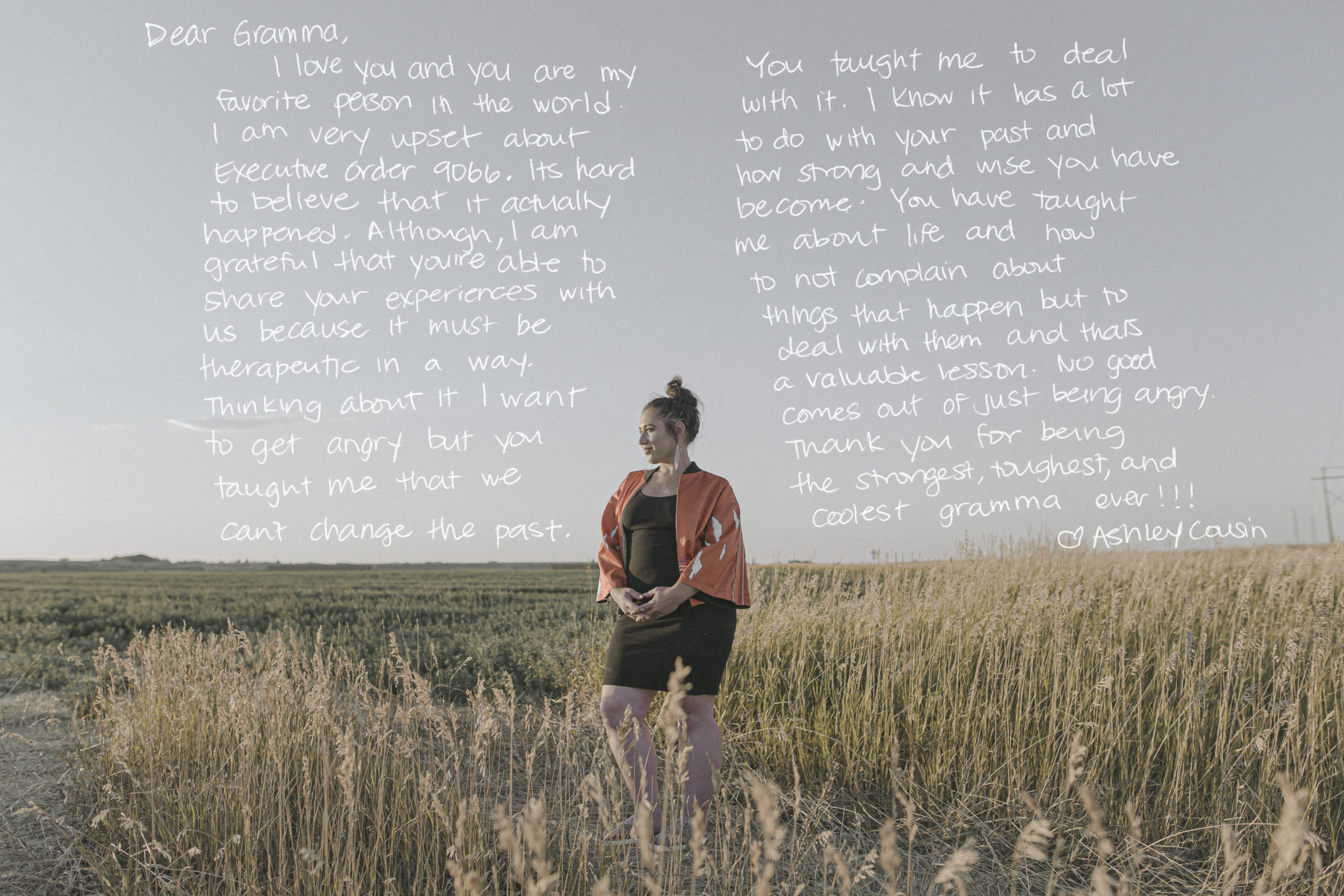

Ashley Emiko Cousin is the maternal grand-daughter of Yoshiko Josie Shintaku Okamoto. She was born in San Francisco.

Growing up, Ashley says Josie often commented on how similar she is to her own mother, Shigeko. “I’m reincarnated by my great grandmother,” she says. “My grandma always tells me that.” Ashley recounts an incident when she and her family visited Shigeko’s grave when she was six years old. “Her grave was in a random little town near Lodi. It was a van of us, and I gave directions there. I’ve never been there before. I told them exactly where to go, and when we stopped the car, I jumped out,” she says.

Although Ashley knew about the camps from a young age, she began to learn more about Josie’s experience when she began to receive diary-like emails from her describing her wartime memories starting around 2017. The emails would begin with a date—from 1941 to 1945—and describe a moment, like her family’s departure to camp, in sensory detail.

Ashley senses that she is a generation removed from her family’s history. “I think this would be more something [belonging to] my mom’s generation because they see a little more firsthand,” she says. “But we’re her grandkids. I don’t really have as much of a connection with it.”

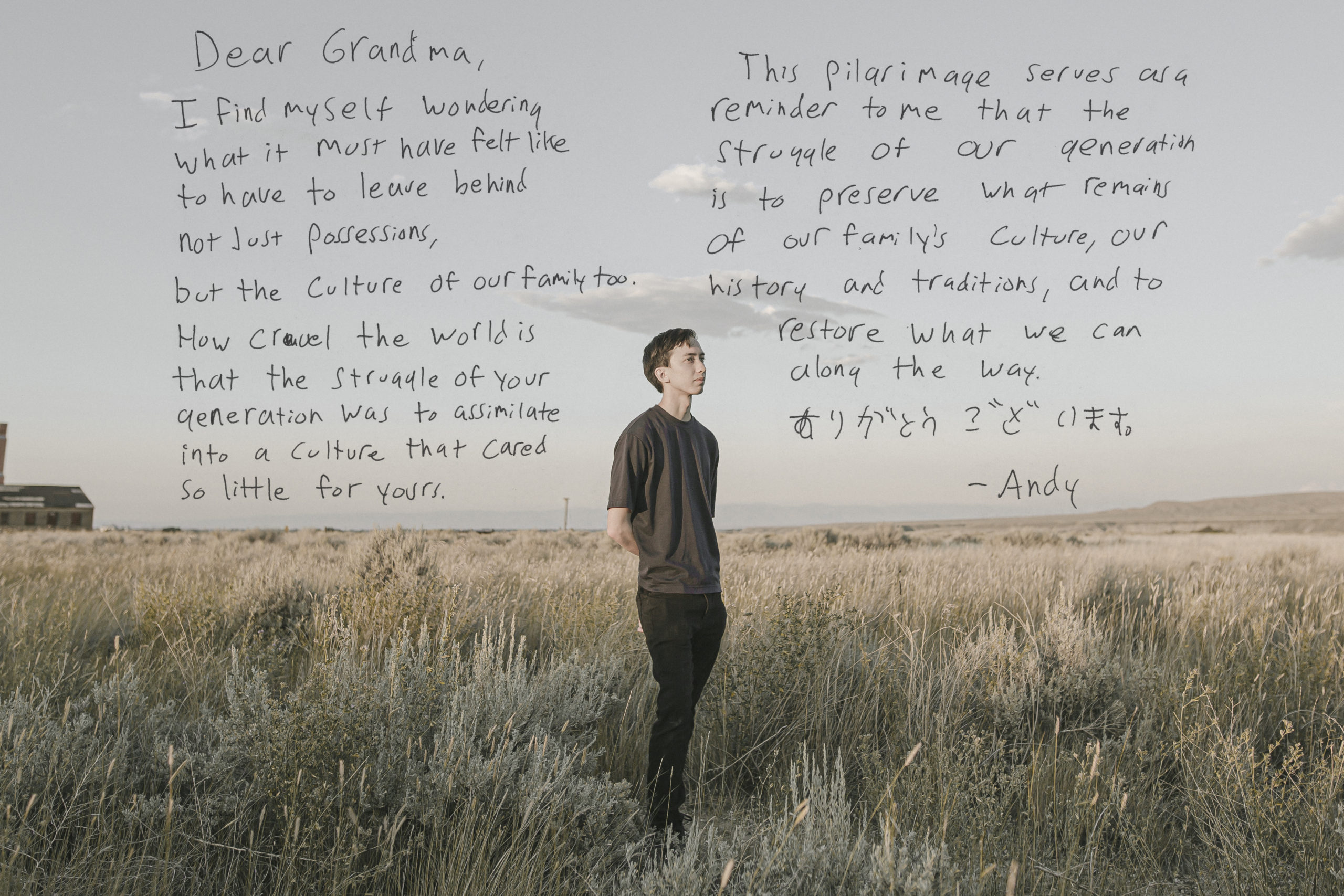

Andrew Jin Kotik is the maternal grandson of Yoshiko Josie Shintaku Okamoto. He was born and raised in Palo Alto, CA.

Andrew is the only member of his family who speaks Japanese. From a young age, he attended Japanese summer school at a local Buddhist church and visited Japan for the first time in middle school through a cultural exchange program. “I really think that that was the moment when I was like, ‘Okay, I really want to invest all my time into engaging with the culture,’” he says. “I realized that no one else in my family speaks Japanese and that kind of bummed me out.”

Although his family did not refrain from talking about the camps, Andrew says conversations about that time period were typically short and lighthearted. “I think a big trait that runs in my family—and honestly probably runs in a lot of different Japanese families—is the overwhelming feeling of guilt as a motivating factor,” he says. “Just an attitude of not wanting to bring trouble to other people and not wanting to be a burden on other people. I think that’s why my grandmother wasn’t very talkative about her experiences for a long time. She didn’t want to burden other people with her sad stories.”

Andrew says he sees similar traits in his mother—and in himself as well. “I struggle with feeling like a burden and feeling ashamed of myself if I don’t do as much as I can for my community and my family,” he says. “I think that’s part of why I’ve been motivated to learn Japanese so much is that I’d feel guilty if none of the grandkids were engaging with the culture or not putting in any work to keep it alive in the family.”

Andrew continued his Japanese studies throughout high school and is interested in studying linguistics in college. He aspires to live in Japan one day.

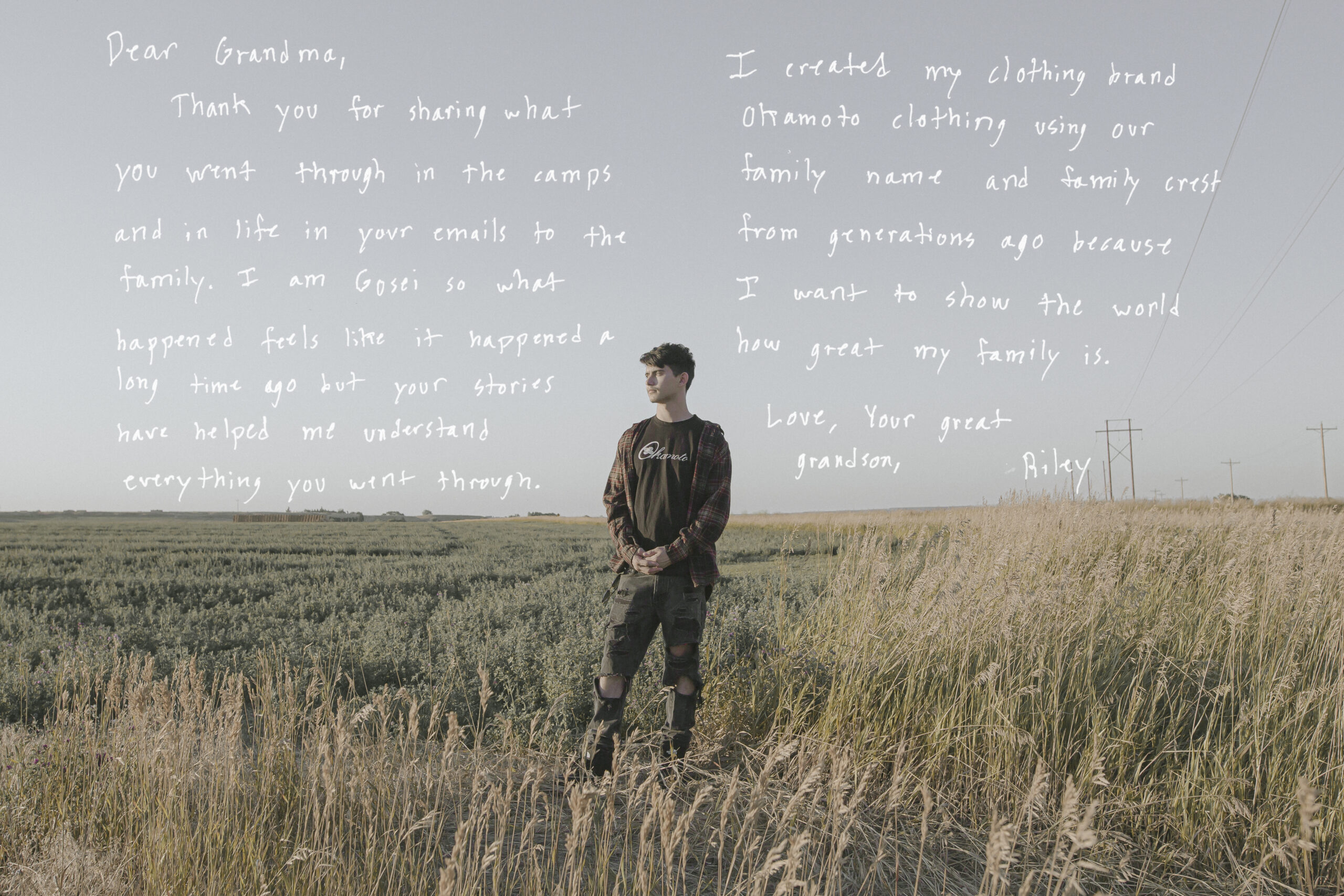

Riley Grant Okamoto is the paternal great-grandson of Yoshiko Josie Shintaku Okamoto. He was born in Elk Grove, CA.

Although Riley has been aware of his family history from a young age, he says he prefers not to ruminate on it. “I don’t really like to dwell on things that happened to my family in the past, especially because it doesn’t affect me that much. I didn’t go through it. My great-grandma did and it affected her,” he says. “But she’s always stood strong. I’ve never heard her complain and be like, ‘Woe is me, I had to go through this.’”

Riley says his grandfather Rodney is one of his role models. “He was the first generation to be out of the camps, and he decided he was going to help the family. He went to college and got his degree in pharmacy, then helped his brothers and sisters go to college, […] helped me go to college, my little brother go to college,” he says. “That’s why he’s my role model. He decided he was going to carry everything on his shoulders and provide for the family.”

In 2020, Riley founded a namesake fashion label. His logo was inspired by his family crest, identified on a family member’s headstone from many generations ago. “My family is very supportive of me and what I choose to do with my career choices,” he says. “My great-grandma, I want to keep her close. So I have my brand, Okamoto Clothing, to keep the name alive.”