“We were very confined. But on the other hand, we had to make the most of it and enjoy it, regardless of the situation.”

— Louise Nakashima Nishikawa

Listen to this portrait.

Louise Nakashima Nishikawa

Nisei

Louise Nakashima Nishikawa was born in Loomis, CA and grew up on a farm in Carmichael, CA. When Executive Order 9066 was issued, Louise’s family was a month shy of harvest. They were left with little choice but to ask a neighbor to pick their crop for the season.

At the age of 18, Louise—the eldest of four children—was tasked with signing the paperwork administered by the War Relocation Authority on behalf of her Issei parents before she and her family were sent to Pinedale Assembly Center. It was a nerve-wracking experience. “My parents didn’t speak English well,” she says. “As the oldest child, I had to grow up fast.”

After a few months at the Pinedale Assembly Center, Louise and her family were transferred to Block II of the Poston concentration camp—a days-long journey by rail. “We couldn’t see out the windows because they pulled down the shades,” she says. “They didn’t want us to look outside.” Upon their arrival, Louise and her family were given salt tablets to cope with the summer heat.

During her time in Poston, Louise recalls being a forward on the camp basketball team and a leader of the camp Girl Scouts. She also spent her time making adobe bricks—which the camp buildings were made out of—and camouflage nets for the U.S. Army. “We were very confined,” she says. “But on the other hand, we had to make the most of it and enjoy it, regardless of the situation.”

In spring of 1944, Louise’s family was given two options: to stay in Poston or to leave early and move somewhere away from the west coast, as part of the War Relocation Authority’s resettlement program. Louise’s family relocated to Payette, ID and worked on a friend’s potato farm for several years before they were able to move back home to California.

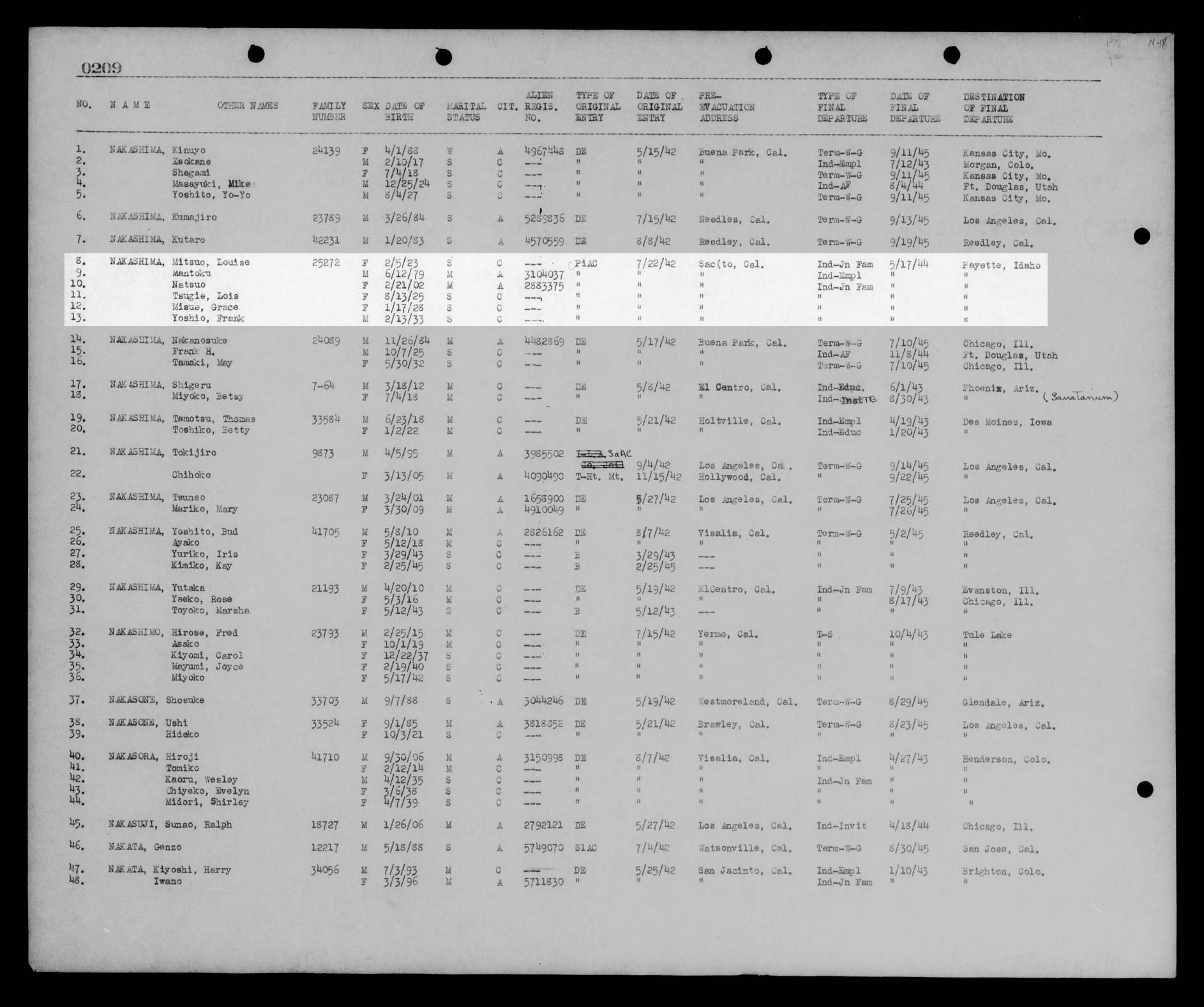

Louise’s information as it appears in the Final Accountability Roster for Poston. Courtesy of Densho Encyclopedia.

Listen to this portrait.

Reid Nishikawa

Sansei

Reid Nishikawa is the son of Louise Nakashima Nishikawa. He was born in Sacramento, CA and spent his early childhood in Yuba City, CA.

Reid says he first became aware of his family history when he was about 10 years old. “My mom would refer to it as ‘camp.’ She wouldn’t really talk in great detail about that experience,” he says. When she did speak about her incarceration, his mother focused on the clubs and sports teams she used to be a part of. “My mom was just involved in a lot of different activities, whether it was sports or the Girl Scouts or making bricks or camouflage nets,” he says. “What my mom’s actions in camp taught me is you can’t change the circumstances around you, but you can change how you react to those circumstances. You can complain about being incarcerated and you can be bitter, but then that sort of eats you from the inside out.”

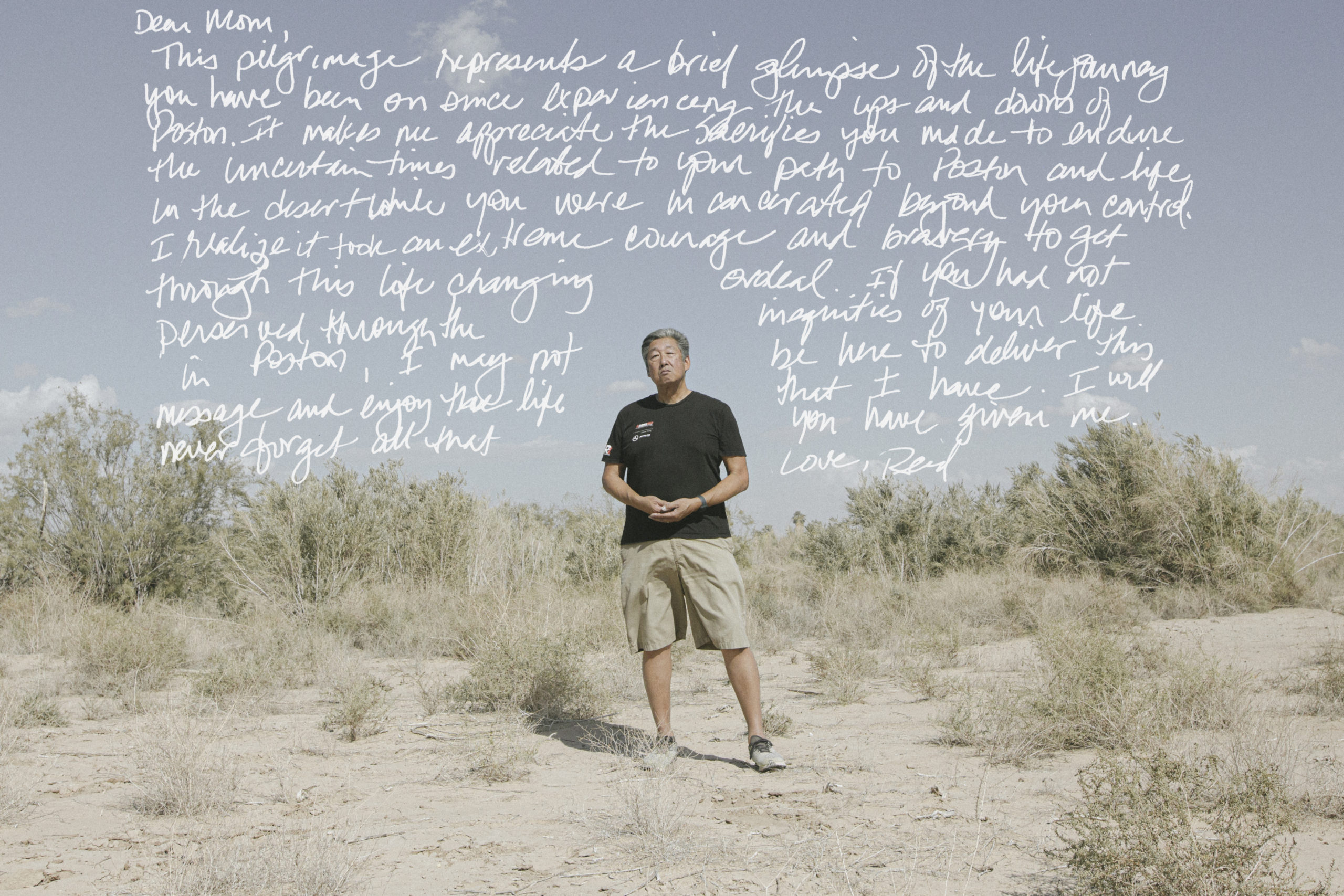

For Reid, visiting Poston is a reminder that he is part of a larger narrative. “It’s almost like returning to the beginning,” he says. “Your DNA came through that camp, and you carry that same DNA throughout your whole life. Then your DNA is transferred to the next generation. It’s really a spiritual experience to go there.”

Reid is the Chair of the Poston Memorial Monument Committee and a Board Member of the Poston Community Alliance. “If our parents weren’t strong enough and didn’t persevere enough, it’s entirely possible that we might not be here,” he says. “That’s why I think I volunteer my time to these organizations.”