Located in Owens Valley about 225 miles northeast of Los Angeles, Manzanar is arguably the most well known of the 10 War Relocation Authority concentration camps. It was situated on 6,000 acres of desert terrain adjacent to the Sierra Nevada mountain range, where summer temperatures reached 110 degrees and winter temperatures dipped below zero. The region was marked by high winds and choking dust storms.

Before settlers arrived in the 19th century, Owens Valley was inhabited by the Nüümü, who called the region Payahuunadü, or “Land of Flowing Water.” The area was lush with water fed by streams descending from the Sierra Nevadas and carefully preserved by the Nüümü’s sustainable agricultural practices. However, early settlers forcibly removed the Nüümü, and the City of Los Angeles quietly bought up land and water rights in the region—including that of Owens Lake—to supply water to its fast-growing population. By the time Japanese Americans were incarcerated here during World War II, Owens Lake had become a toxic dry lake and the largest source of dust in North America.

Manzanar concentration camp with a view of the Sierra Nevadas in the distance. June 30, 1942. Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration.

Manzanar concentration camp with a view of the Sierra Nevadas in the distance. June 12, 2022.

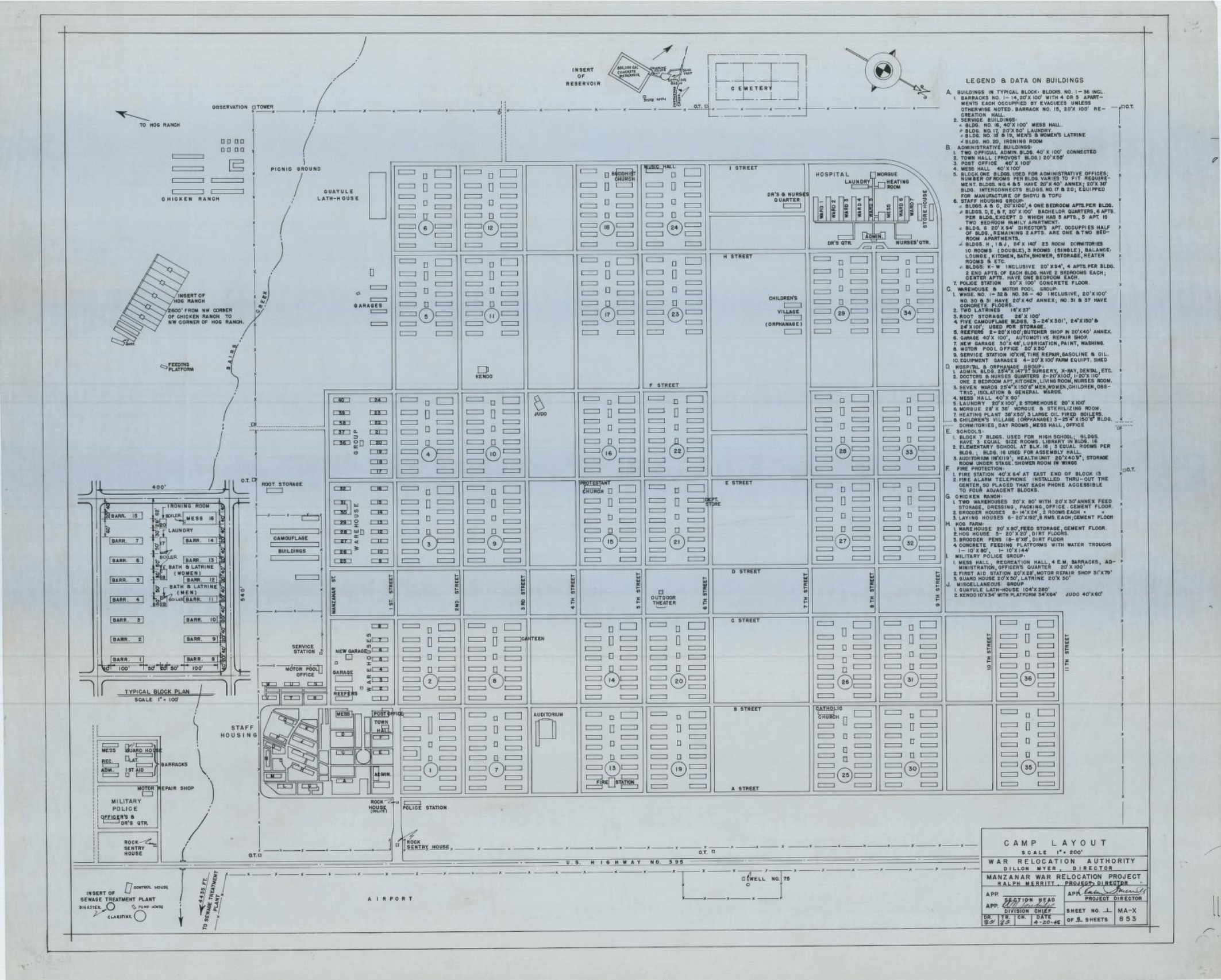

Most of Manzanar’s incarcerees came from the Los Angeles area. The first incarcerees arrived in March of 1942 as volunteers to help build the camp. By June, nearly all incarcerees had arrived, but the camp was still far from complete. Incomplete barrack blocks caused overcrowding, forcing up to a dozen people to live in a single 20 x 25 unit. The sewage and water supply systems were incomplete, and tests showed high pollution levels—including traces of E. coli—leading to dysentery throughout the camp.

Located in a remote desert over 200 miles outside of Los Angeles at the base of the Sierra Nevadas, Manzanar was one of the many camps afflicted by extreme weather and choking dust storms.

One of the remaining original structures at Manzanar is the Manzanar Fire Department. The wood and tar paper buildings in camp caught fire frequently. Incarcerees worked together to develop a fire protection system to help protect their community. Over the course of the war, incarceree firemen successfully battled 91 fires.

Incarcerees engaged in sports like baseball, football, basketball, soccer, volleyball, softball and martial arts to make life more tolerable. They even built a nine-hole golf course on the camp premises.

Communal gardens like Merritt Park—perhaps ironically named after the camp director Ralph Merritt—were designed and maintained by incarcerees to improve morale and provide gathering spaces for other incarcerees and their children.

Despite these challenges, the incarcerees found ways to improve their living conditions. They nailed tin can lids over knotholes in their barracks to keep out the dust, and they dug subterranean spaces to escape the summer heat. They planted lawns and communal gardens to beautify the camp and mitigate dust storms, including the renown Merritt Park, a traditional Japanese garden complete with a pond, bridges, and even a teahouse.

Incarcerees planted orchards to combat the frequent dust storms. Still, dust was an ongoing problem, and former incarcerees report chronic respiratory issues from their years spent at Manzanar.

Owens Lake, a toxic dry lake located outside of the Manzanar concentration camp, is the largest source of carcinogenic particulate air pollution in North America.

Most incarcerees worked for meager wages in the camp. Jobs included digging irrigation canals, growing produce, working in daily camp operations and making camouflage nets to support the war effort. Many incarcerees pooled their resources to form a camp cooperative, which published the Manzanar Free Press and operated a general store, beauty parlor, barbershop, and bank.

When the camp closed on November 21, 1945, many incarcerees from the Los Angeles area had a difficult time finding housing, due to persistent anti-Japanese sentiment and redlining. Those who ventured back to Los Angeles on short-term leave to look for housing returned to Manzanar, frustrated by their inability to find homes. Of these, many relied on hostels, boarding houses and government housing to start a new life after the war.

Why is Manzanar significant?

Pilgrimage attendees gather around a bonfire at the inaugural pilgrimage to Manzanar in December of 1969. Courtesy of Manzanar National Historic Site and the Evan Johnson Collection.

Aside from being the most photographed and visited of the 10 War Relocation Authority camps, Manzanar is known as the site of the first pilgrimage in 1969.

A year after the war ended and the camp was closed, Buddhist minister Sentoku Maeda and Christian minister Shoichi Wakahiro returned to Manzanar to honor those who died while incarcerated and could not go home after the war. Since then, they journeyed back to the desert every year to commemorate the dead. Eventually, this grew into a larger movement led by Japanese American student activists, who were inspired by the Civil Rights Movement. In 1969, they organized a community-wide pilgrimage as part of a campaign to repeal the Emergency Detention Act of 1950, a law that codified the camps where Japanese Americans were incarcerated during WWII. About 150 people were present at the inaugural pilgrimage.

Today, the Manzanar pilgrimage draws over a thousand attendees from across the country. Most of the 10 former camps offer their own annual pilgrimages to commemorate their ancestors and reflect on this dark chapter in American history.