“You kicked me out of the Army and put me in this hell hole.”

— Keige Kaku

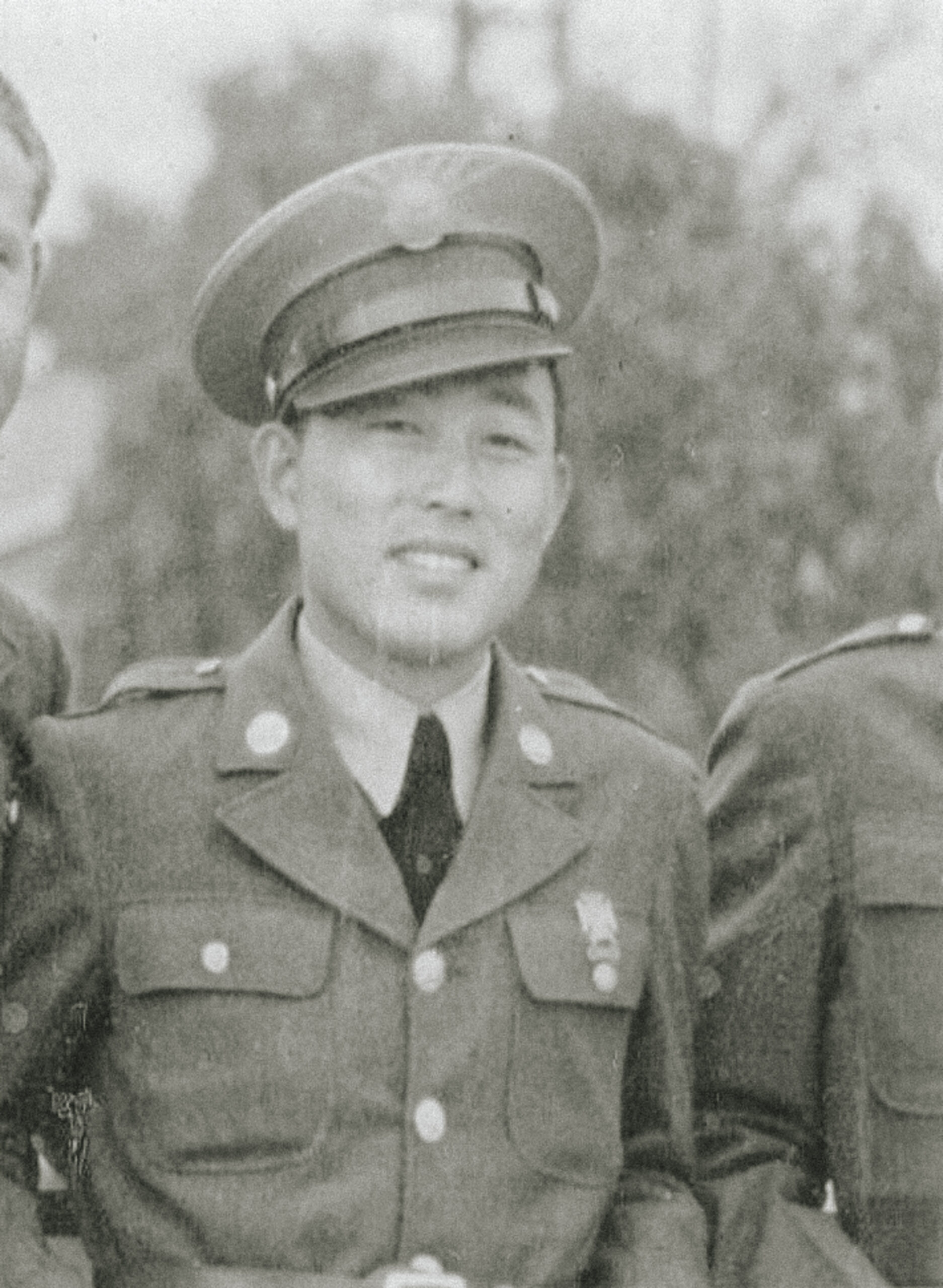

Keige Kaku

Nisei

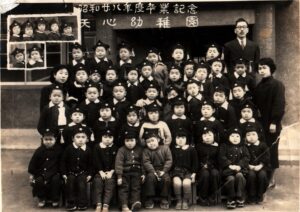

Keige Kaku was born in Orosi, CA. When he was six years old, his parents contracted tuberculosis and returned to Japan, leaving Keige in the care of distant family members in Brawley, CA.

When Keige was 25 years old, he enlisted in the U.S. Army. He was stationed in Georgia with the Army Corps of Engineers when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. Within a month, he was discharged from the Army while his unit prepared for deployment to Europe.

After his discharge, Keige, still in his military uniform as he had no other clothes, took a bus from Georgia to California. He tried hitchhiking for the final stretch, but no one picked him up. He walked 14 miles to reach his family’s home, only to learn that his father had been arrested by the F.B.I., and his mother was preparing for their impending “evacuation.”

When evacuation posters began appearing around town, Keige went to the War Relocation office to request a one-month delay in their evacuation date so his family could finish harvesting their crops. “They flatly refused me, even with my Proof of Reserve paper,” he recalled in a testimony he prepared during the Redress Movement. With no other options, Keige joined his mother and family at the Santa Anita Assembly Center and was later transferred to Poston.

In a display of defiance and pride, Keige arrived in Poston wearing his U.S. military uniform. “He probably walked in with his chest out, saying, ‘You’re pointing your rifle at me? I’m wearing the same uniform as you,” his son Henry reflects. Keige was assigned to be a block manager, but he was eventually fired after protesting his incarceration and encouraging other incarcerees to do the same. During this time, he married Sumiko, a fellow incarceree from Brawley, and they welcomed their daughter Joyce while still in camp.

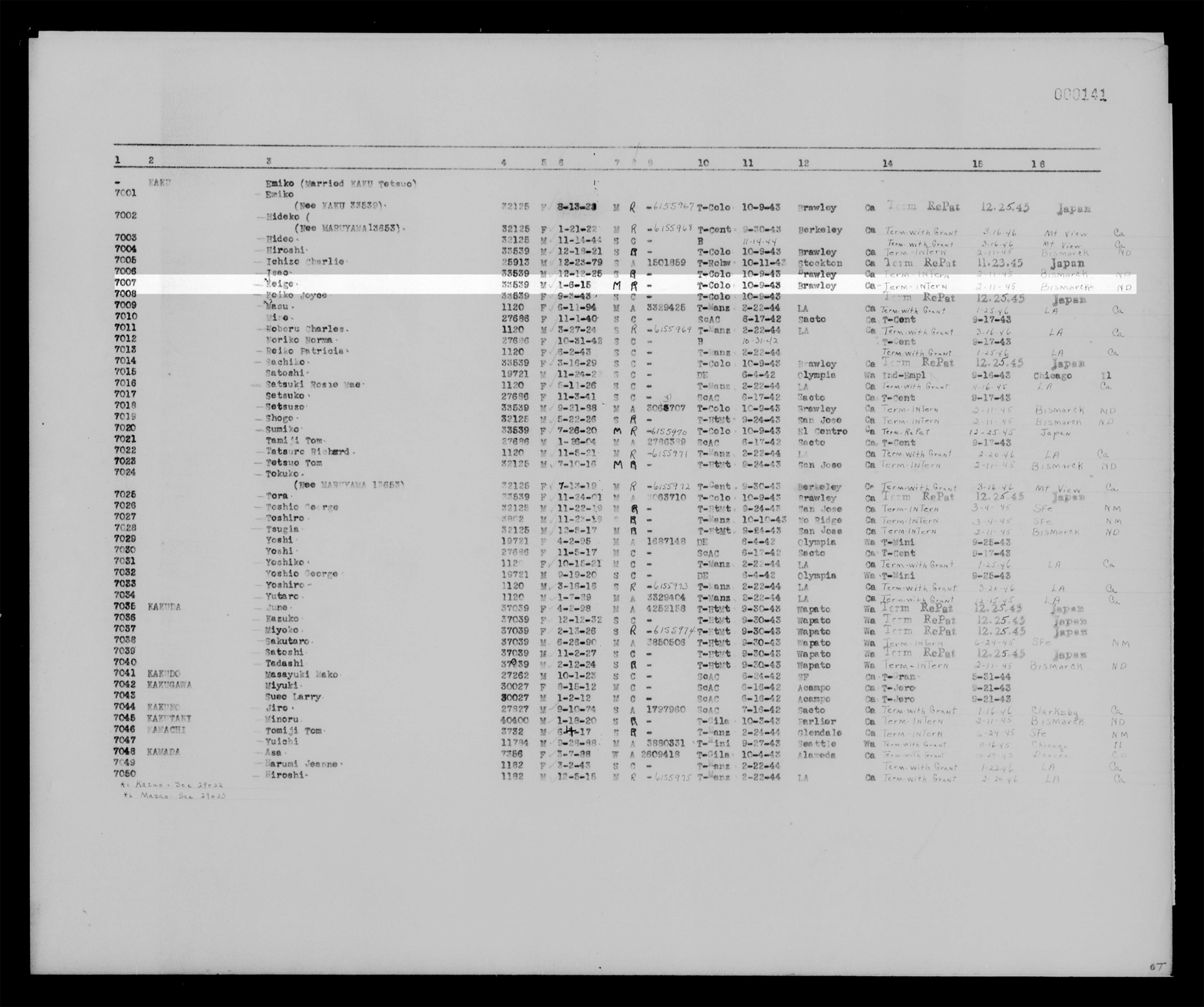

In 1943, the government issued the infamous loyalty questionnaire, which Keige refused to answer. Having already served in the military, he told officials, “You kicked me out of the Army and put me in this hell hole.” His refusal to comply earned him the label of “no-no boy,” and he and his family were transferred to Tule Lake Segregation Center. In 1945, Keige was forcibly separated from his family and sent to Fort Lincoln Internment Camp, during which time Sumiko gave birth to their son, Stanley.

After four years of incarceration and nearly a year apart, Keige and Sumiko made the difficult decision to renounce their U.S. citizenship. In March of 1946, the Kaku family was deported to Japan.

Life in post-war Japan was bleak. Keige and his family moved frequently, staying with various relatives as they struggled with severe food shortages. “My mother often said they didn’t think Stanley would survive because there was no food,” Henry recalls. Employment was hard to come by, as neither Keige nor Sumiko were Japanese nationals. Stripped of their U.S. passports, they found themselves stateless.

After months of hardship, Keige and Sumiko found work at a U.S. military base in Kokura. “This was the same military that he got kicked out of,” says Henry. “Now he was hired by them.” In 1948, their youngest son, Akira, was born.

After nearly a decade of forging a life in Japan, Keige learned of civil rights attorney Wayne M. Collins’ efforts to help renunciants restore their U.S. citizenship. “America was their country, although they were no longer citizens,” says Henry. “They grew up for the first 20, 25 years of their life in America. They’d always wanted to come back.” With Collins’ support, they successfully argued their case in court, and in 1956, the Kaku family regained their U.S. passports and returned to California.

Upon arriving in San Francisco, Keige and Sumiko chose to begin anew. “When we got off the ship, my parents told us we weren’t going to speak Japanese anymore,” Henry recalls. “I didn’t know a single word of English.” They decided to change their son’s name from Akira to Henry and settled in Palo Alto, where Keige worked as an independent gardener for over forty years to support his family. He passed away in 2009.

Keige’s information as it appears in the Final Accountability Roster for Tule Lake. Courtesy of Densho Encyclopedia.

Listen to this portrait.

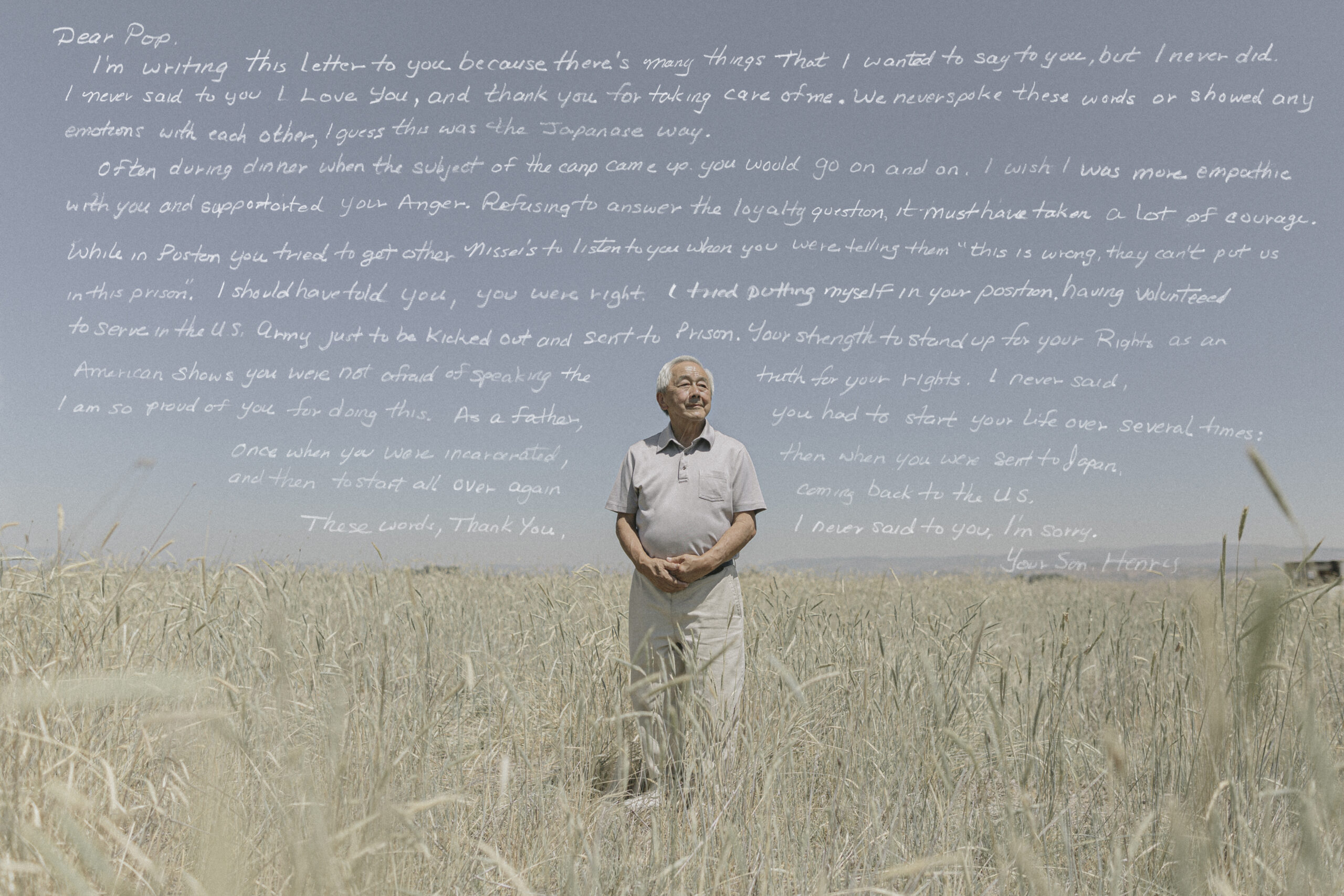

Henry Kaku

Sansei

Henry Kaku is the son of Keige Kaku. He was born and raised in Japan, where his family was deported after renouncing their U.S. citizenship. “I have no recollection of this period in my life,” he says. “It’s a total mystery. Total blank.”

Henry was eight years old when his family reclaimed their U.S. citizenship and returned to the States. “I was born with the name Akira,” he recalls. “When my parents came back from Japan and we were driving in the car, they said, ‘Akira needs an American name.’ Someone in the car mentioned, ‘Well, there’s a candy bar called Oh Henry!’ So without any legal name change, they said, ‘Akira, you are now Henry.’”

Adjusting to his new life in Palo Alto, CA, wasn’t easy. “When I first came to America, I couldn’t speak one word of English,” he explains. Placed in the first grade—two years behind his peers—he found himself isolated. “I didn’t have friends to play with after school, so I would come home, study my English, and then just sit and do origami,” he says.

Growing up, Henry says his father often voiced frustrations with both the U.S. government and other Japanese Americans. “Some people think my father was a hothead,” Henry shares. “He would often tell us over dinner that he was in a no-win situation. When he was in Poston, he was called ‘inu’ [by other incarcerees] for speaking out about being incarcerated. In Tule Lake, he was called ‘inu’ again because others thought he was a spy, having served in the U.S. Army.”

Over the years, Henry has come to understand his father’s struggles more deeply. “I now have a small sense of what he went through,” he reflects. “I wish I could tell my father that I now understand that whether you answered yes or no to Question 27 or Question 28, they’re both different ways of saying you are a loyal American.”