“I just remember the sense of guilt. I was old enough to realize that we’re in prison—a prison with barbed wire, guards with rifles. That we did something wrong. That I did something wrong.”

— Kazuo Ideno

Listen to this portrait.

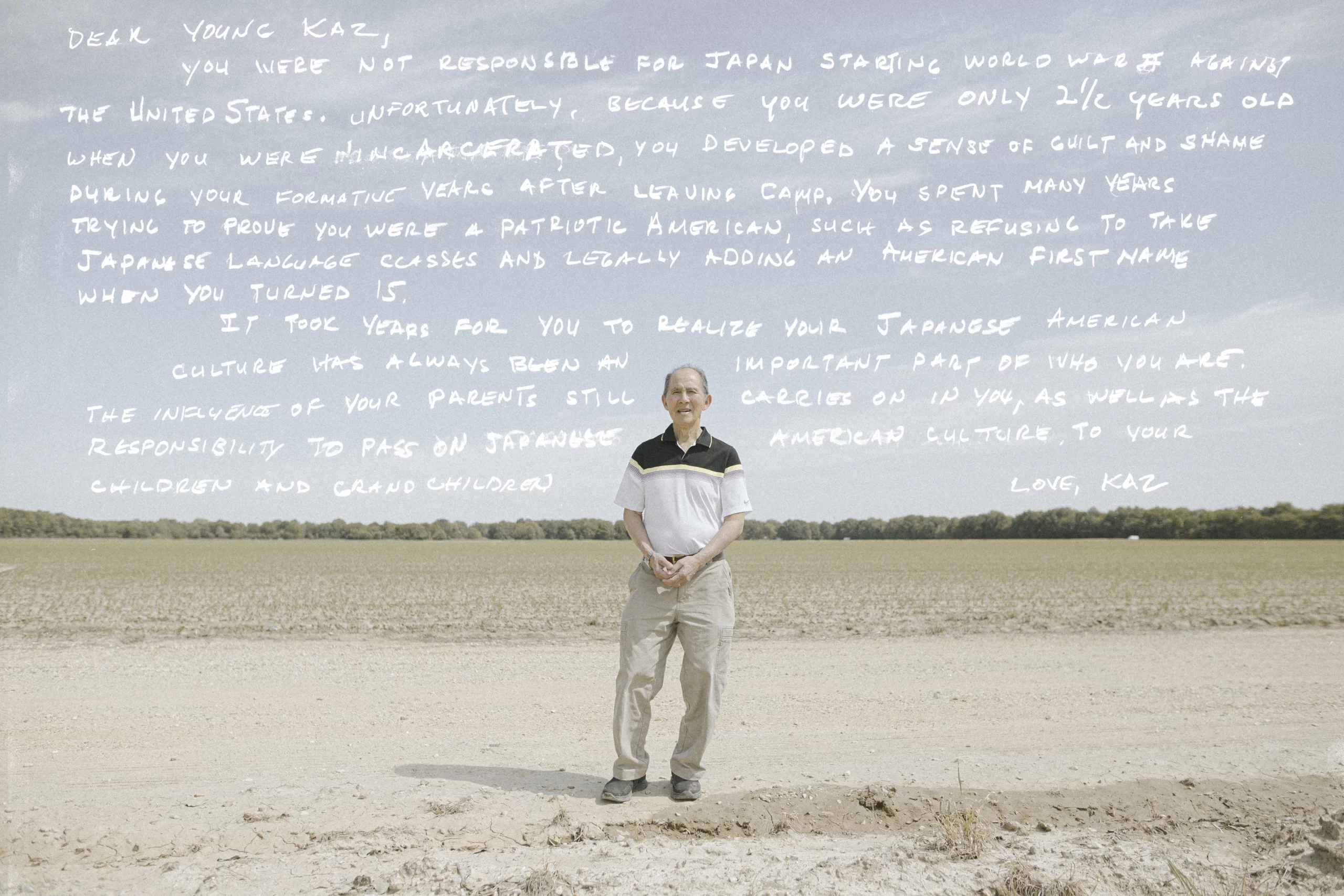

Kazuo Ideno

Nisei / Sansei

Kazuo Ideno was born in the San Francisco Bay Area to an Issei father and a Nisei mother. Shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Kazuo’s father—a kendo instructor who ran a local dojo—was taken by the FBI and detained at the Santa Fe Internment Camp in New Mexico. Within weeks, Kazuo’s mother, brother and he were sent to the Santa Anita Assembly Center for six months and transferred to Rohwer for several months before reuniting with his father at the Crystal City Internment Camp during the summer of 1943.

Kazuo remembers that his father looked “beaten down” after their long-awaited reunion. Years later, he learned that during his time in Santa Fe, a drunken guard had stabbed his father in the back with a bayonet. On another occasion, Kazuo’s father was ordered to dig a burial site for fellow incarcerees who were shot by a guard. Prior to the war, Kazuo’s father worked as a bookkeeper and kendo instructor. “After that, it was all menial jobs,” Kazuo says. “He lost a lot of ambition.”

Upon their release, Kazuo’s parents moved to New Jersey to work at a cannery before moving to Illinois to run a boarding house outside of Chicago. In high school, Kazuo decided to change his name to Gene—a decision he attributes to his formative years in camp. “I just remember the sense of guilt. I was old enough to realize that we’re in prison—a prison with barbed wire, guards with rifles. That we did something wrong. That I did something wrong,” he says. “I think that’s one of the motivations for why I wanted to […] show that I’m an American. I wanted to do everything I could to prove that fact.”

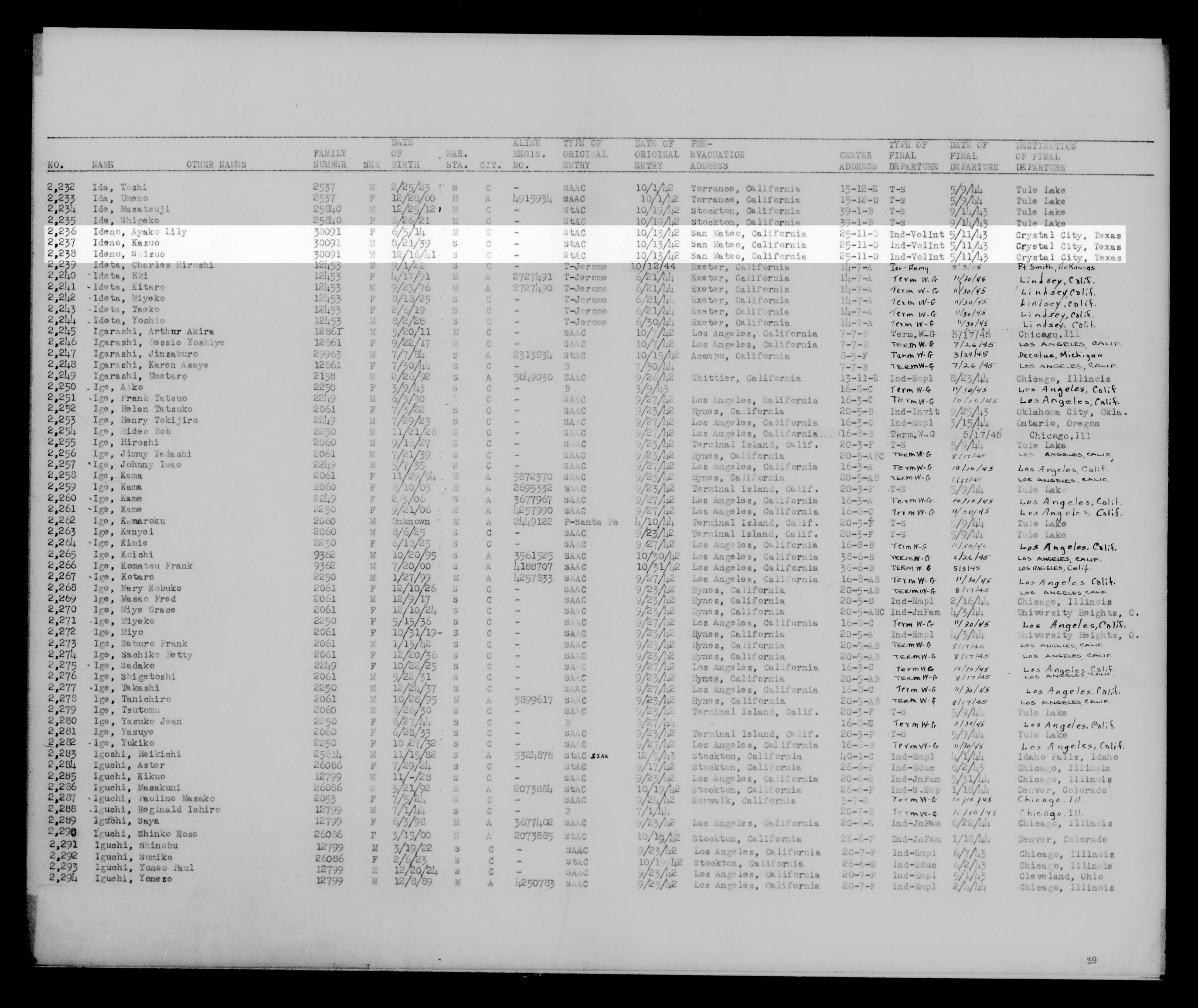

Kazuo’s information as it appears in the Final Accountability Roster for Rohwer. Courtesy of Densho Encyclopedia.

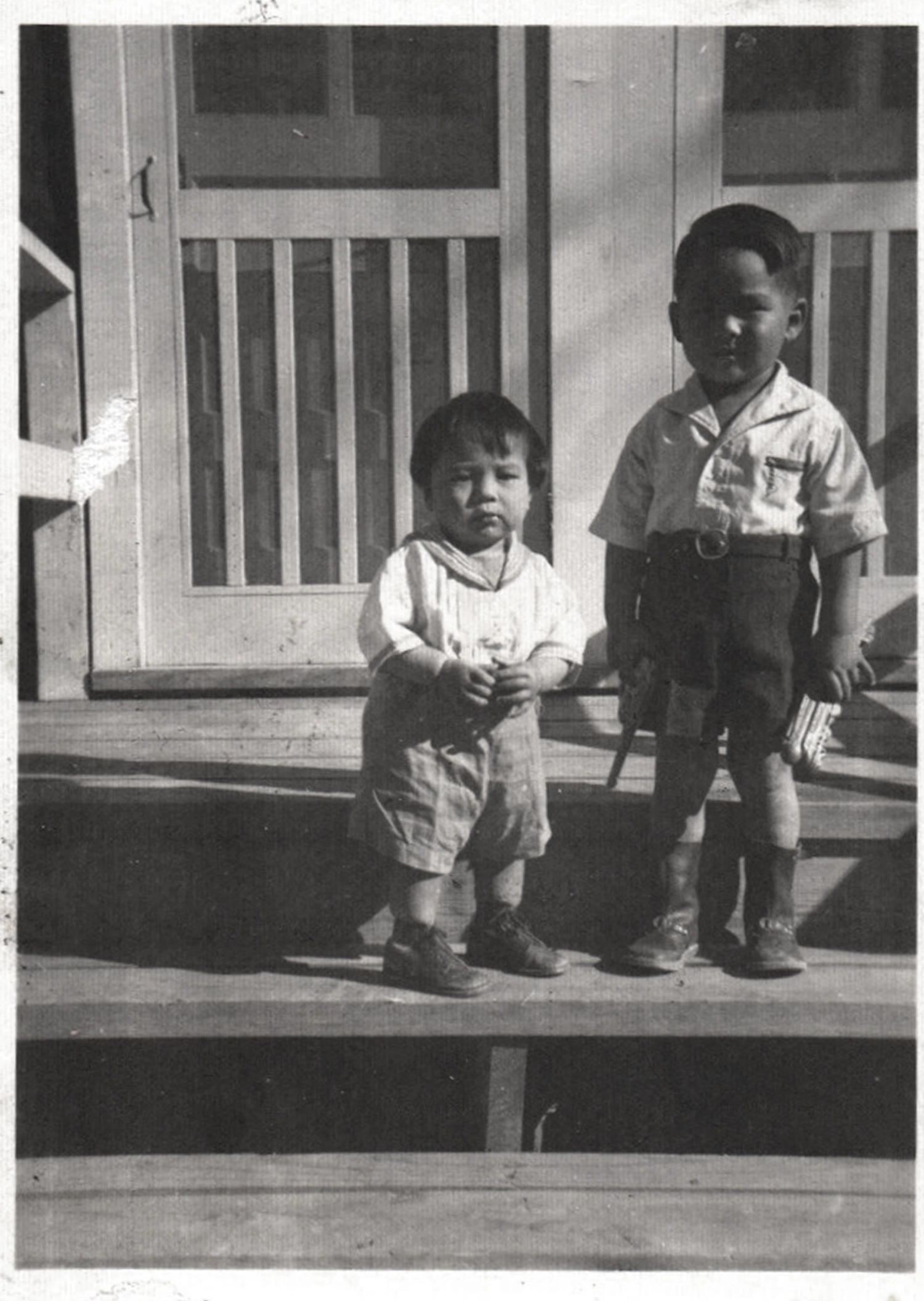

Kazuo’s younger brother Shizuo (left) and Kazuo (right) in front of their barrack (25-11-D) in Rohwer, circa 1942. Courtesy of the Ideno Family Collection.

Listen to this portrait.

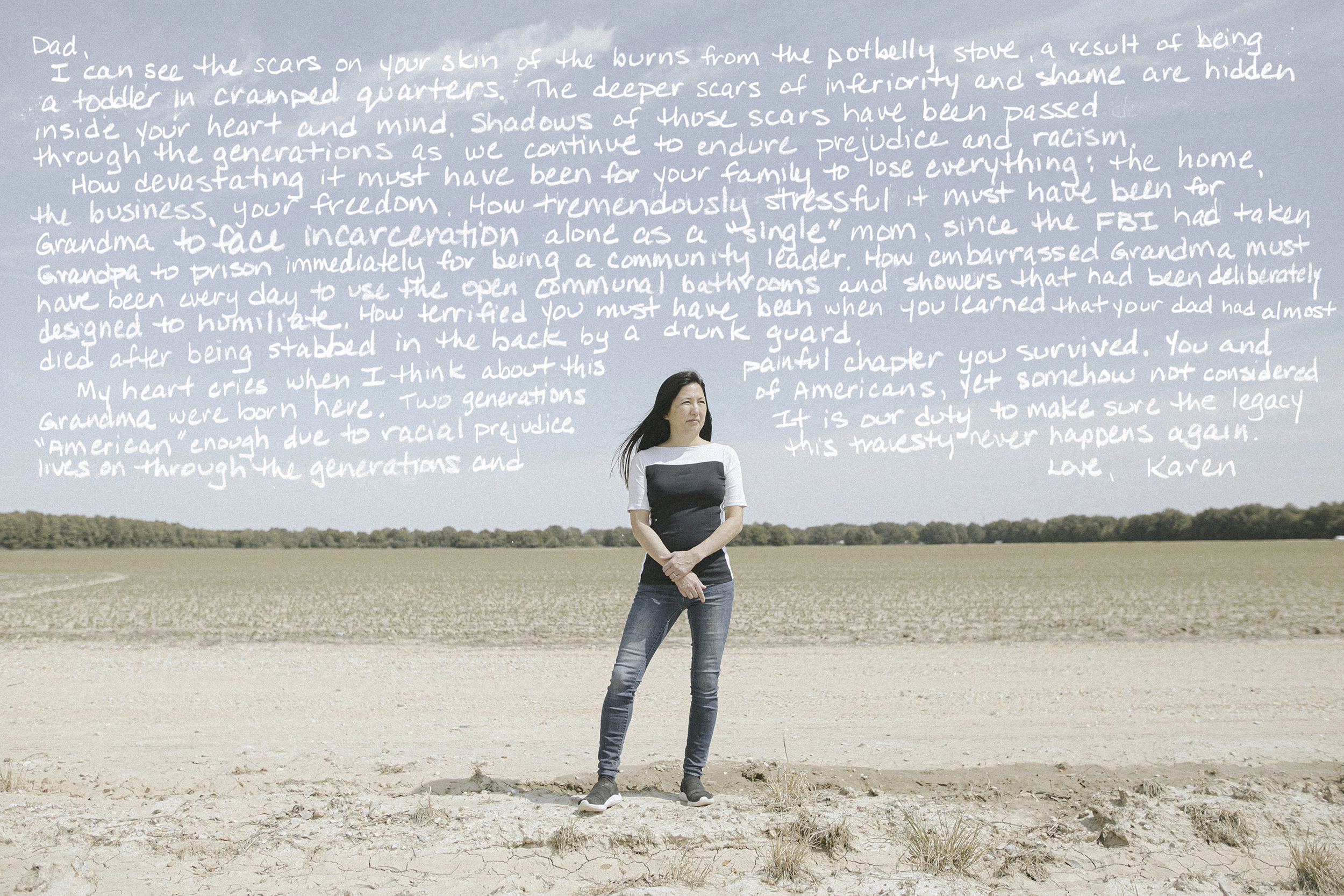

Karen Ideno-Chiou

Yonsei

Karen is the daughter of Kazuo Ideno. She was born and raised in the Chicago area. Growing up, Karen says most of her peers were Caucasian. “We were the token Asians,” she says. “So I tried to prove that I was American as much as I could. Similar to my dad, I pushed my Japanese heritage away. I played all the American sports—volleyball, basketball, track and soccer.”

Karen says she experienced a shift in the third or fourth grade when fellow students called her a racial slur. “I came home and I was crying to my dad. I’m like, I wish I weren’t Japanese. I wish I were Italian or you know, Irish or some Caucasian heritage, but not Japanese,” she says. “And I remember my dad getting really mad. He said, ‘You be proud that you’re Japanese’. And that really had an impact on me. Because after that, I didn’t complain.”

During her sophomore year in college, Karen studied abroad in Kobe, Japan. She was the first person in her family to visit the country. “My parents hadn’t been there. My maternal grandmother had never even visited Japan,” she says. “She had no desire because she considered herself American. She […] never wanted to set foot there because of the internment camps.” There, Karen says she was able to meld her two cultural identities. “In Japan, I learned that I’m so proud to be American. But yet at the same time, I’m proud to be Japanese too,” she says.

“I came home and I was crying to my dad. I’m like, I wish I weren’t Japanese. I wish I were Italian or you know, Irish or some Caucasian heritage, but not Japanese. And I remember my dad getting really mad. He said, ‘You be proud that you’re Japanese’. And that really had an impact on me. Because after that, I didn’t complain.”

— Karen Ideno-Chiou

Listen to this portrait.

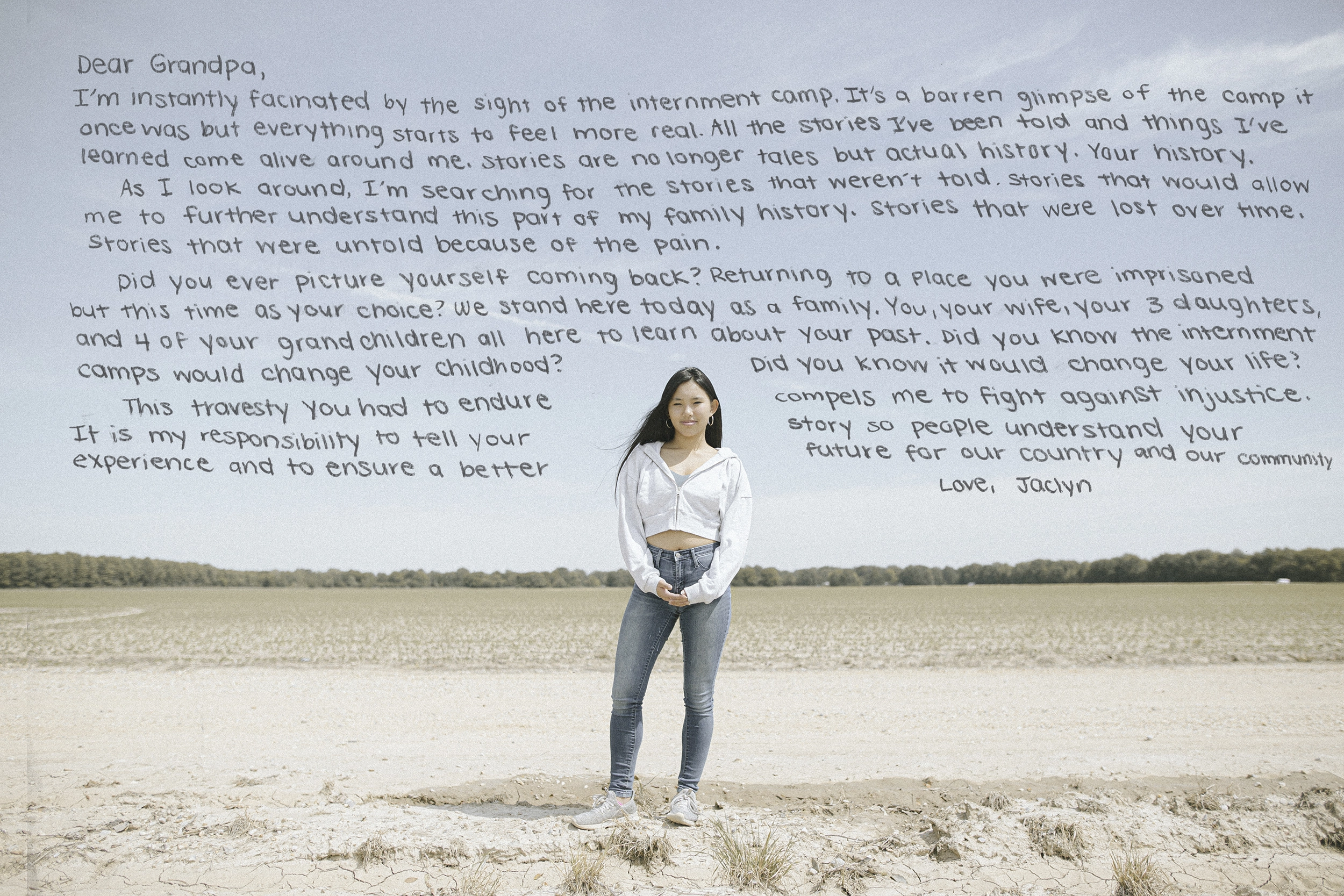

Jaclyn Chiou

Gosei

Jaclyn is the maternal grand-daughter of Kazuo Ideno. She was born in the Chicago area to a Japanese American mother and Taiwanese American father. She first learned about the incarceration of Japanese Americans when she interviewed her great-grandmother for a history project in the fourth grade. “It was one of the first times I’d ever seen my great grandma cry,” she says. “I think there’s a lot of P.T.S.D. and trauma still there.”

This experience has inspired Jaclyn to join an Asian American civic leadership program in high school. “I think learning about how America isn’t this crazy happy place, that things still happen […] has made me really want to fight for what I believe in,” she says.

Even though she did not grow up among many Japanese Americans, Jaclyn says she has inherited some traits from her cultural heritage. “Learning about how patient and kind a lot of the Japanese Americans were—despite being treated like prisoners—has really influenced how I go out into life,” she says. “I take the Japanese mindset into how I live my life today and how I interact with others.”

“Learning about how patient and kind a lot of the Japanese Americans were—despite being treated like prisoners—has really influenced how I go out into life.”

— Jaclyn Ideno-Chiou

Listen to this portrait.

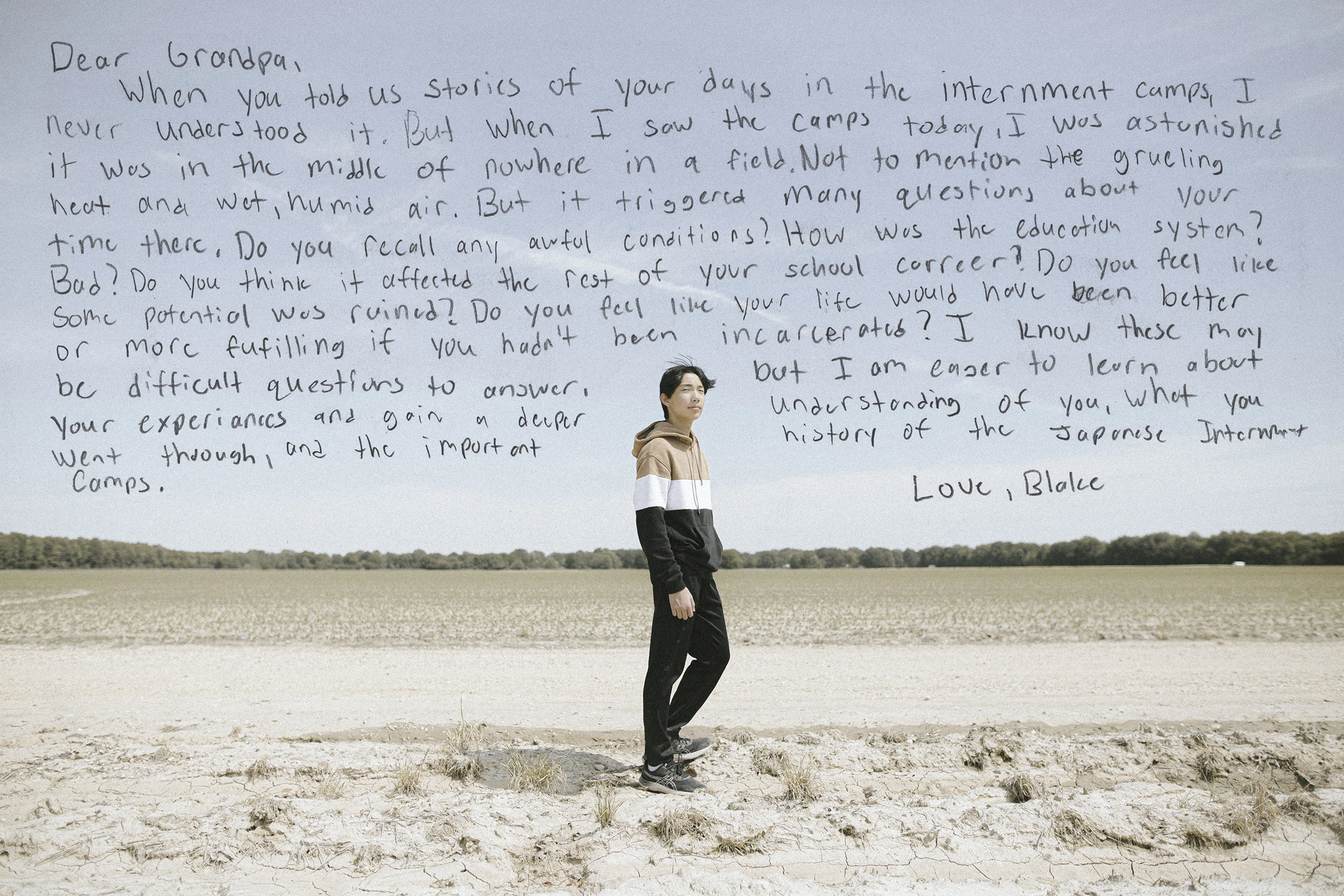

Blake Chiou

Gosei

Blake is the maternal grandson of Kazuo Ideno. He was born in the Chicago area to a Japanese American mother and Taiwanese American father. While he did not know many Japanese Americans growing up, Blake felt connected to his Japanese heritage whenever he and his family participated in the annual Obon festivals in Chicago. “My whole family grew up dancing,” he says. “We did it from such a young age. We had a really fun time.”

Growing up, Blake says he knew about his family’s incarceration from a young age. “I don’t necessarily have a first memory,” he says. “It’s something I’ve always just known. My parents told me about it from a pretty young age, so it’s always been there.” While he has always known about the camps, Blake says he may not understand his grandfather’s experience in full detail. “I never really had serious talks with my grandpa,” he says. “It was more like, ‘Let the adults do the talking.'” Visiting Rohwer in person has helped Blake fill in some sensory details—like the humidity and stark isolation—in his family history. “Words don’t speak as much as experiencing it,” he says.