“When we came back, when we went to go get our belongings, there was nothing there. Nothing except for broken boxes, empty boxes. Maybe a few broken dishes.”

— Hatsuko Mary Yoshioka Higuchi

Listen to this portrait.

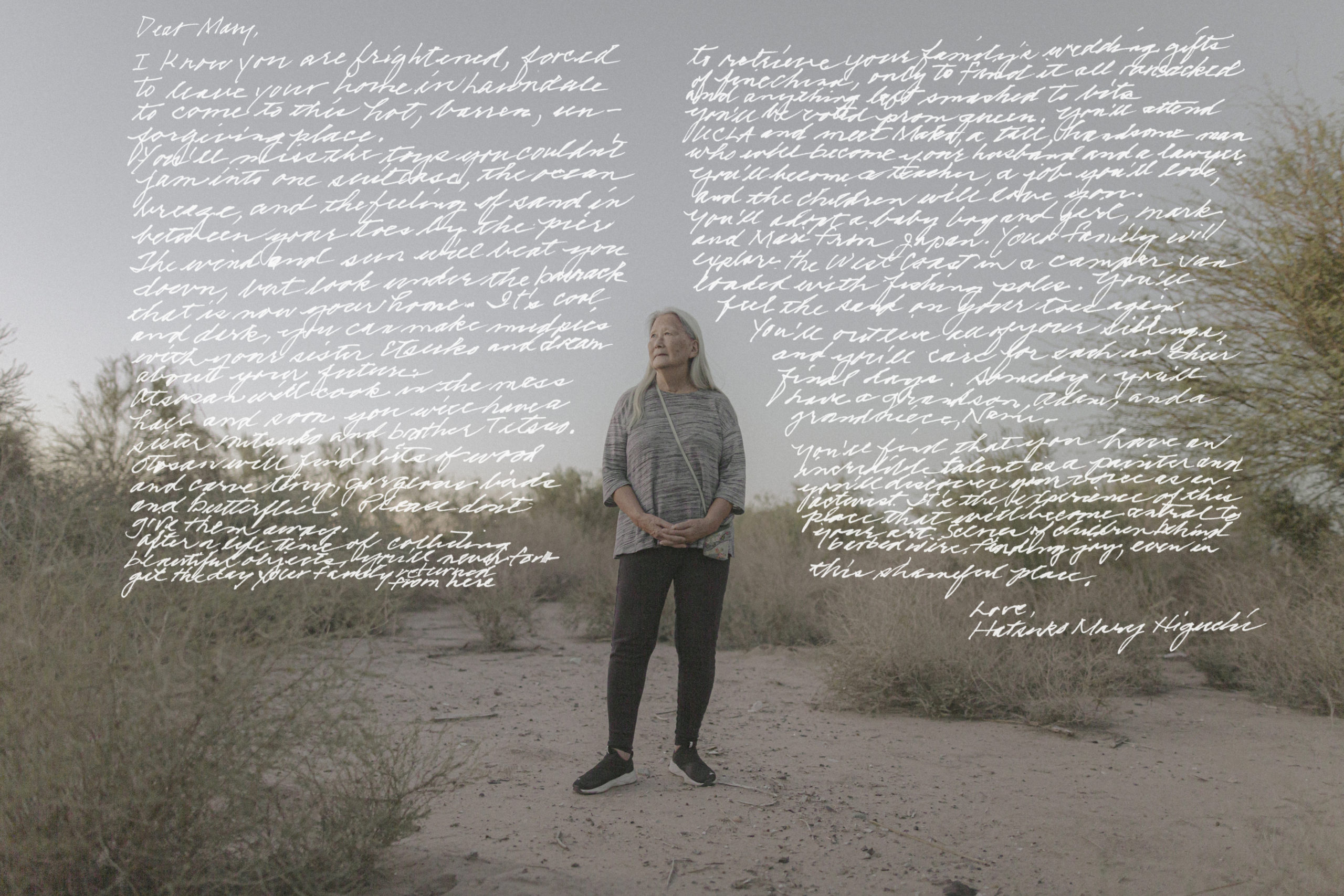

Hatsuko Mary Yoshioka Higuchi

Nisei

Hatsuko Mary Yoshioka Higuchi was born in Los Angeles between an Issei father and a Kibei mother. She was three years old when she and her family were imprisoned at Poston.

Mary’s family’s barrack was sparsely furnished. “My father [built] a kitchen table and chairs to sit on. He hung bed sheets for walls to separate, to have privacy,” she says. Mary also recalls sharing one large bed with her siblings and making regular trips to a faucet near their barrack to retrieve water. “I think it was a very difficult situation. Moving into a barrack with none of your furniture, none of the things that you had, starting life all over,” she says.

Prior to their incarceration, Mary’s family had stored their belongings in a barn. When they returned to retrieve their belongings after the war, they found the barn empty. “There was nothing there. Nothing except for broken boxes, empty boxes. Maybe a few broken dishes,” she says. With no home to return to, Mary’s family moved to a house with no indoor plumbing. Her father built an wood-fired ofuro in the backyard. It took Mary’s family nearly a decade to save enough money to put a down payment on farmland that they could call their own.

Shortly after they acquired their land, however, Mary’s father died of a heart attack, leaving her mother to raise her and her three siblings single-handedly while running the farm on her own. “She couldn’t speak English and she didn’t have any skills to get a job, so she decided to farm those 10 acres,” Mary says. “She’s never farmed before. She started working everyday on that farm tilling the soil.”

At school, Mary and her siblings were given American names by their teachers. “Rather than Hatsuko, Etsuko, Mitsuko, and Tetsuo, they gave us Mary, Betty, Nancy and Jimmy,” she says. “Nancy later changed her name to Mitzi, and my brother changed his name to Tetsu. He never went by Jimmy.”

Mary’s mother continued to operate the farm while putting her four children through school. “When my father died, [my mother] knew nothing. […] And she had to pick up and carry on,” she says. “But she never complained. Never, never complained. Never wanting us to be different and deprived of anything. We always had everything we needed for school, our clothes—made sure we were dressed like everyone else.”

Mary’s information as it appears in the Final Accountability Roster for Poston. Courtesy of Densho Encyclopedia.

Listen to this portrait.

Sachi Cunningham

Sansei

Sachi Cunningham is the maternal niece of Hatsuko Mary Higuchi and the daughter of Mary’s sister, Mitsuko, who was born in Poston.

Growing up, Sachi spent her summers with Mary in Los Angeles, where she attended Japanese classes at a local Buddhist temple and danced at the Obon festival. “It’s largely what shaped me and my desire to travel,” she says. “I loved learning about my culture.”

Her family’s incarceration is also a core part of Sachi’s identity. “I’ve been hospitalized twice for bipolar disorder,” Sachi says. “There is nobody on either side of my family who’s had the same mental illness experiences I have. So it’s always been this question mark.”

Sachi says this could be in part due to her mother being born and spending her formative years in camp. “She was born with all of the eggs she would have for her life, which means that she’s spent the first four years of her life with my egg,” she says. “I believe personally—it’s just my own semi-scientific deduction—that since my mom was born there, I essentially was born there, too.”

“She was born with all of the eggs she would have for her life, which means that she’s spent the first four years of her life with my egg. I believe personally—it’s just my own semi-scientific deduction—that since my mom was born there, I essentially was born there, too.”

— Sachi Cunningham

Listen to this portrait.

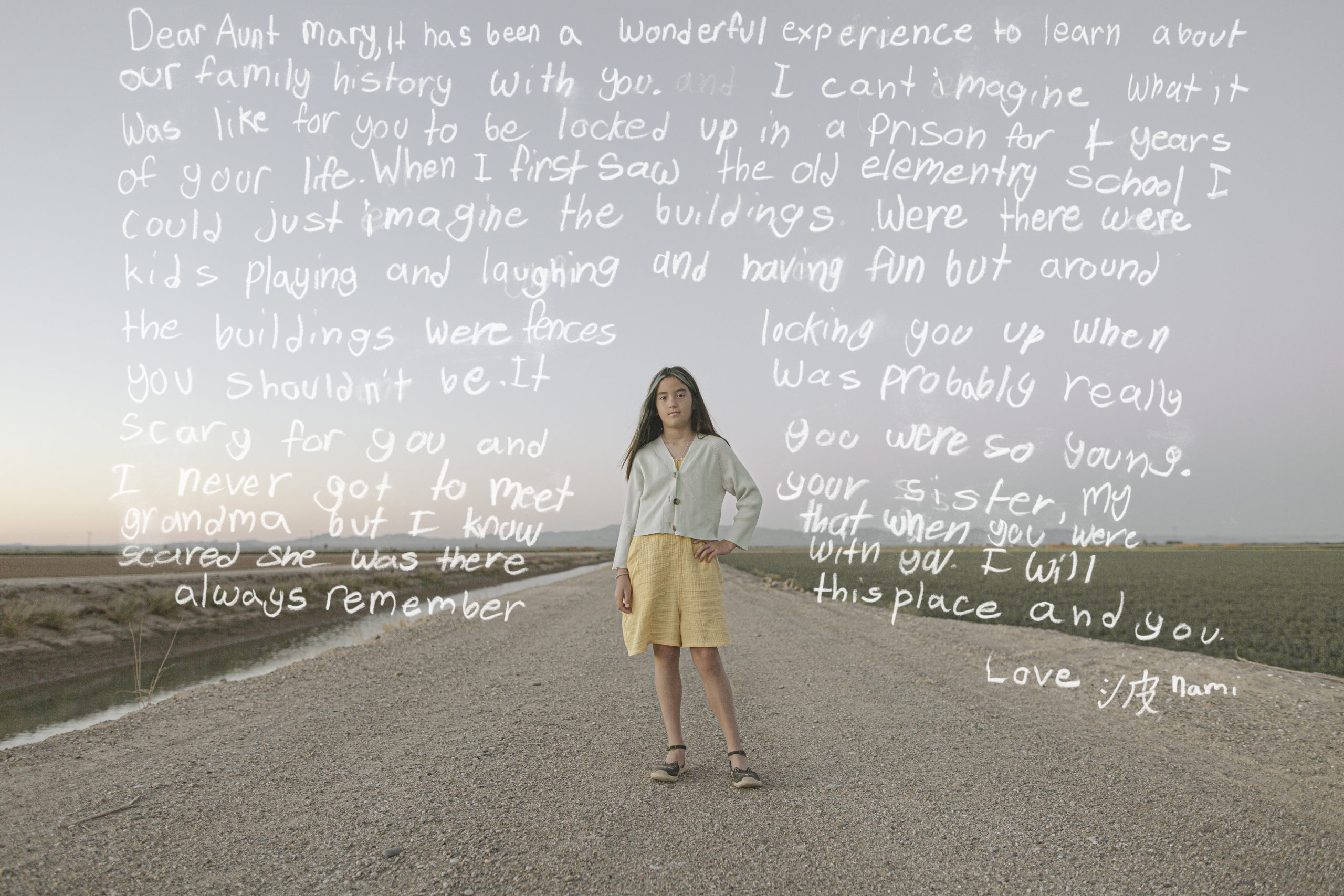

Nami Mitsuko Slobig

Yonsei

Nami Mitsuko Slobig is the grand-niece of Hatsuko Mary Higuchi and the daughter of Sachi Cunningham. She was born and raised in San Francisco.

Nami says she first heard about the camps from her mother when she was in kindergarten. “She didn’t share a lot […] because I was so young. But she just talked about how our ancestors were locked up,” she says. “I didn’t really care [back then]. But now it makes me feel sad and mad. I know that it’s really wrong and a lot of people suffered from it.”

Nami says visiting Poston was an emotional experience for her family. “My mom cried a lot,” she says. “I could understand why she felt that way. I don’t really know how I felt, but I know how she felt. And I know why she felt that way.”

Still, Nami says the pilgrimage made her feel more connected to her family as well as the rest of her Japanese American peers. “I felt like there were so many people just like me [at the pilgrimage]. I felt like we were all connected, and we had so much in common. […] Like we were all big one family that all had the same things that happened to them and their kids.”