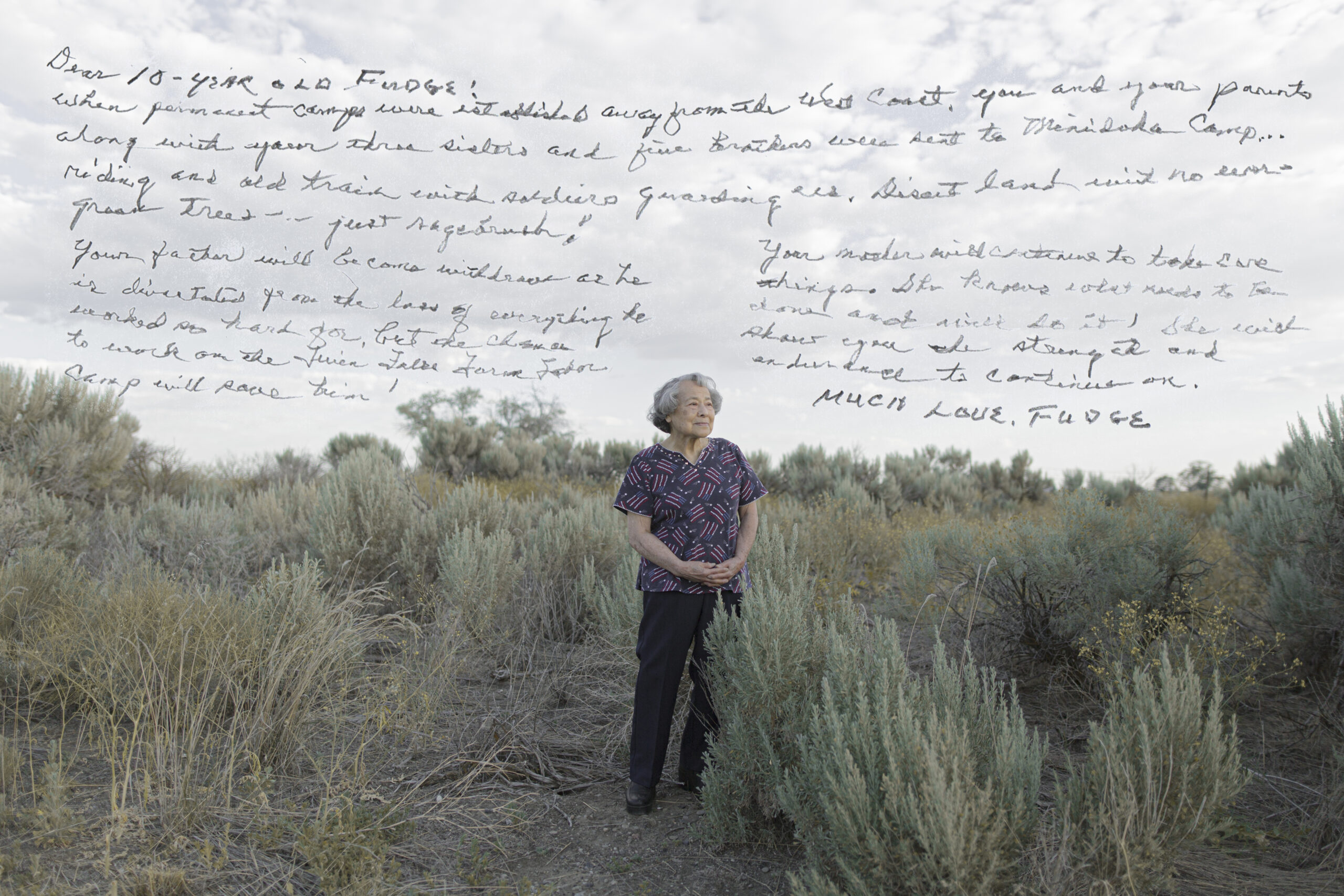

“My father changed so drastically. I think it was because of the disintegration of our family. All the older brothers and sisters were busy getting together with their own friends and going to eat, so you no longer sat at a big kitchen table eating together.”

— Fujiko Tamura Gardner

Listen to this portrait.

Fujiko Tamura Gardner

Nisei

Fujiko Tamura Gardner was born in Fife, WA and raised on a farm by two Issei parents. “We were financially poor, but rich in many ways,” she says. “[We had a] wonderful, large family and a terrific mother. She was a perfect example of a samurai: she was soft and gentle on the outside, but very strong on the inside.”

Fujiko was nine years old when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. Fearing persecution, Fujiko’s family began to burn their belongings that could be traced back to Japan. This included handmade futons that Fujiko’s mother Tamako had painstakingly sewn together from scrap material. “My mom didn’t want us to be traumatized by all these bonfires, so all of that was done when we were in school,” she says. “I have no memory of anything being burned up or being buried on the farm.”

When Executive Order 9066 was announced, Fujiko’s family was told that they could only take what they could carry. Fujiko wanted to take her doll—a rare Christmas gift she had received a few months earlier—but she left it behind due to lack of space. “I would have had to carry the doll because I couldn’t fit it in my suitcase,” she says. “That was one of the sad things I remember as a youngster—that I couldn’t take my beautiful doll with me.”

Fujiko wasn’t the only one who had to leave her prized possessions behind. “Things had begun to look up for us, and we had gotten enough money to buy a tractor, a used Chevy pickup truck and a big delivery truck,” Fujiko says. Weeks before harvest season, Fujiko’s parents were forced to leave behind their newly attained vehicles and sent to Puyallup Assembly Center before being transferred to Minidoka.

On the 30-hour train ride to Minidoka, Fujiko remembers the shades being drawn. “I thought it was to keep the hot sun from coming in,” she says. “But somebody […] said ‘No, that was to keep people from seeing all the Japanese on the train.’” Two songs were playing throughout the train ride: Bing Crosby’s ‘Don’t Fence Me In’, which was popular at the time, and Benny Goodman’s ‘Idaho’. “We didn’t know where we were going, but we knew we were going to Idaho,” Fujiko says. “And that song was just playing continuously.”

Prior to their incarceration, Fujiko’s father Uichi was a hardworking man. But as the days went by, he grew despondent. “My father changed so drastically,” Fujiko says. “I think it was because of the disintegration of our family. All the older brothers and sisters were busy getting together with their own friends and going to eat, so you no longer sat at a big kitchen table eating together.” As his mental health declined, Uichi refused to leave his barrack. “He chose not to go to the mess halls or the latrines,” Fujiko says. Fujiko and her sister brought back meals from the mess hall and changed his chamber pot twice a day. “My mother chose to stay with him because I think she thought that if he found a way, he would have ended his life,” she says.

Eventually, Fujiko’s family found work as live-in farmhands at a nearby labor camp where a limited number of incarcerees could live and work. When Minidoka closed after the war, they continued to work on the farm until the end of harvest because they had nowhere else to go. Aside from the meager wages at the labor camp, their only income was a survivors pension they began receiving after one of their sons died in combat while fighting for the US. They eventually decided to return to their home state and moved into a low income housing project in Tacoma, WA.

Fujiko graduated from the local high school, and her sister helped her land a job as a secretary at a garment company. “Of course, we didn’t have any money to go on to college. But our main goal was to find a good office job—not a factory job—to have enough money to put a down payment on a new house.” A few years later, Fujiko and her sister pooled their funds to move their parents out of the projects and into a new home. “We made sure that mom and dad had a big backyard to grow vegetables in. We tried to get all the modern conveniences in there for them,” she says. Over the years, Fujiko and her siblings worked hard to provide their parents with everything they needed. “The biggest regret I have in my life is that I wasn’t able to take mom and dad to Japan for a visit,” she says.

Despite her family’s hardships, Fujiko prefers to focus on the positive experiences at Minidoka. “I was happy because the older people made sure that we were okay. The older generations made sure that all the kids had Christmas presents during Christmas time. They ensured that we were kept busy doing things, that we were enjoying life in camp,” she says. “These are the stories that need to be told. These stories are what make America great.”

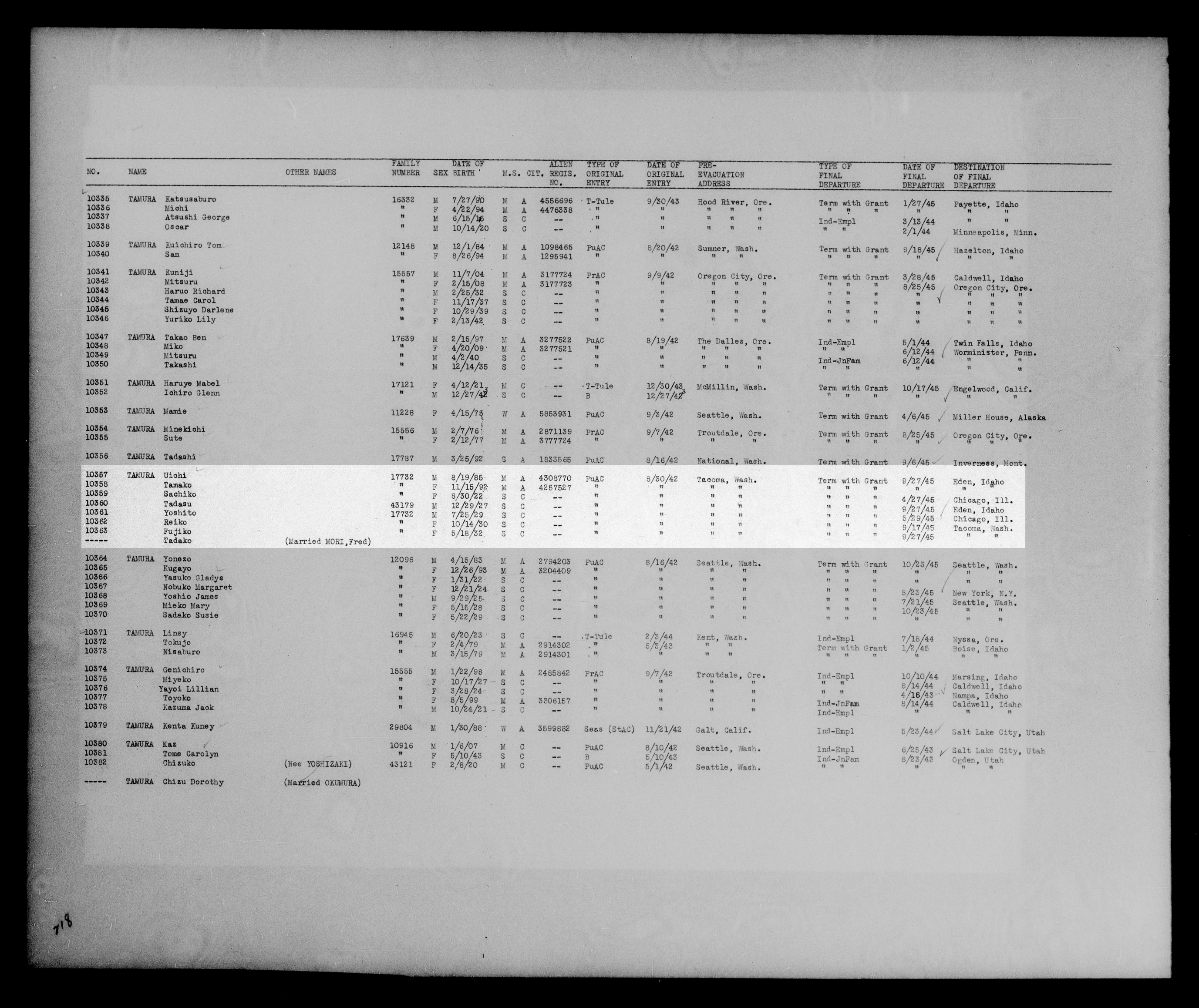

Fujiko’s information as it appears in the Final Accountability Roster for Minidoka. Courtesy of Densho Encyclopedia.

Listen to this portrait.

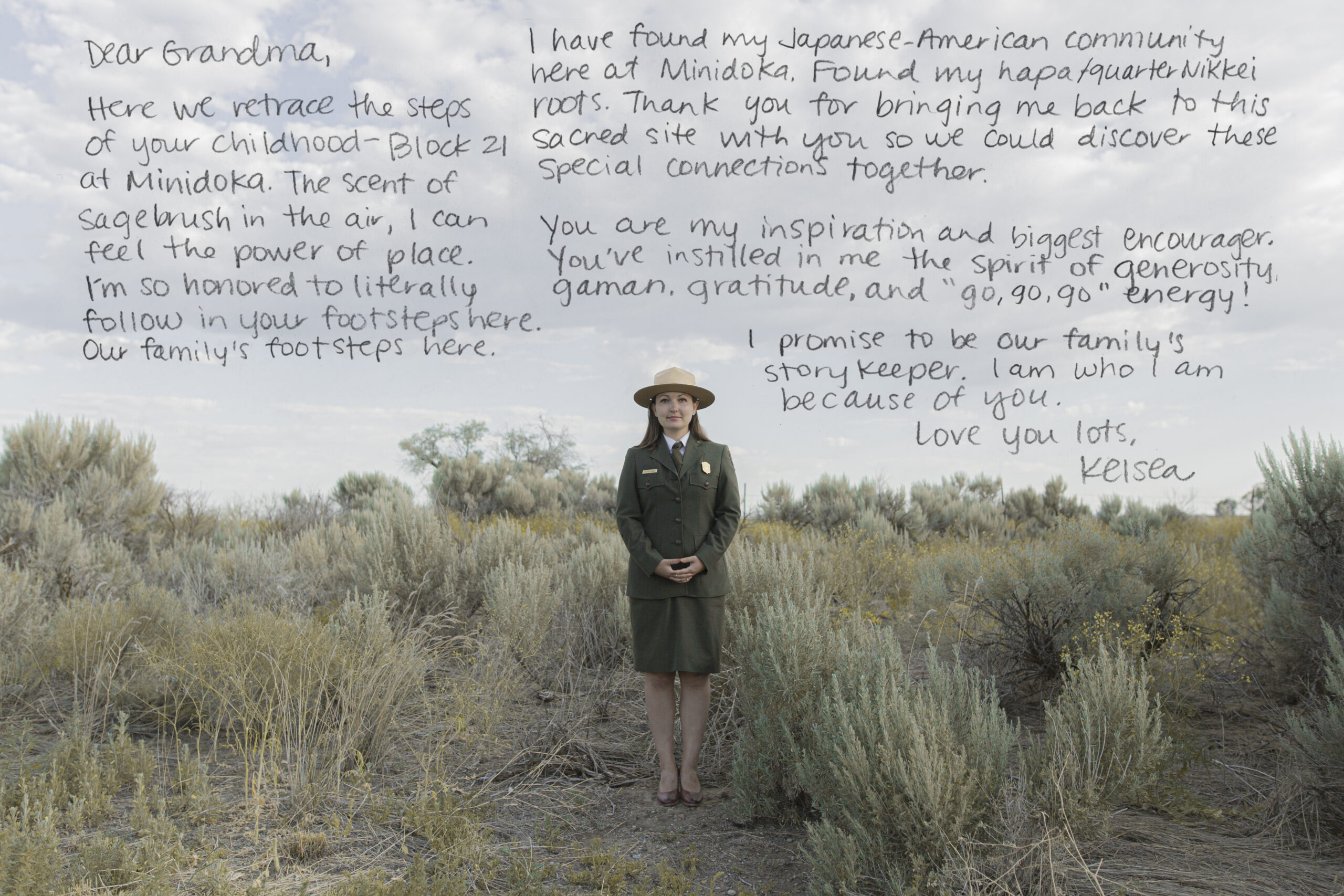

Kelsea Larsen

Yonsei

Kelsea Larsen was born in Seattle, WA and raised in Shelton, WA. She is the maternal grand-daughter of Fujiko Tamura Gardner.

As a mixed heritage Japanese American, Kelsea did not always feel connected to her Japanese heritage. Growing up, being Japanese was more a quirky attribute than a core part of Kelsea’s identity. “It was a fun hidden fact about me,” she says. “In every new class, [when the teacher asked] ‘What’s your fun fact?’ my go-to [answer] was, ‘I’m Kelsea and I’m a quarter Japanese.’” This was often met with surprise and curiosity from her fellow classmates. “I escaped the trap of having an aversion to Japanese identity for the sake of assimilation,” Kelsea says. “But it makes me a little sad that I admittedly trivialized it.”

Kelsea’s perspective began to change when she started to work for the National Park Service in 2009. During a placement at the Pearl Harbor National Memorial in 2011, she met a veteran from the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. When she shared that her great uncles were in the 442nd as well, he asked what company they were in, to which she responded that she didn’t know. “He looked at me, into my soul,” Kelsea says. “He said, ‘Young lady, that’s all available information. You should know that. That’s your family history. That’s your history.” Over the following year, Kelsea began to research her family history to reconnect with her Japanese American roots. “That is actually how I got involved with Minidoka and my family’s story,” she says. “It was at Pearl Harbor.”

As Kelsea uncovered more details about her great uncles, she discovered that one of them was in the same campaign as Senator Daniel K. Inouye, for which he was awarded the medal of honor in 2000. “He was on the battlefront with them,” she says. “I started to see the senator as this great uncle figure.” When Senator Inouye passed away in 2012, Kelsea attended his funeral with a group of veterans from the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. “I carried two pictures in my pocket of [my grandmother’s] two brothers so that I could honor their service while honoring the senator,” she says. “It ended up coming full circle.”

Since then, Kelsea has attended pilgrimages at multiple concentration camps and a commemoration at Bainbridge Island. She currently works as an administrative specialist at the National Park Service.