Coe Family

Heart Mountain

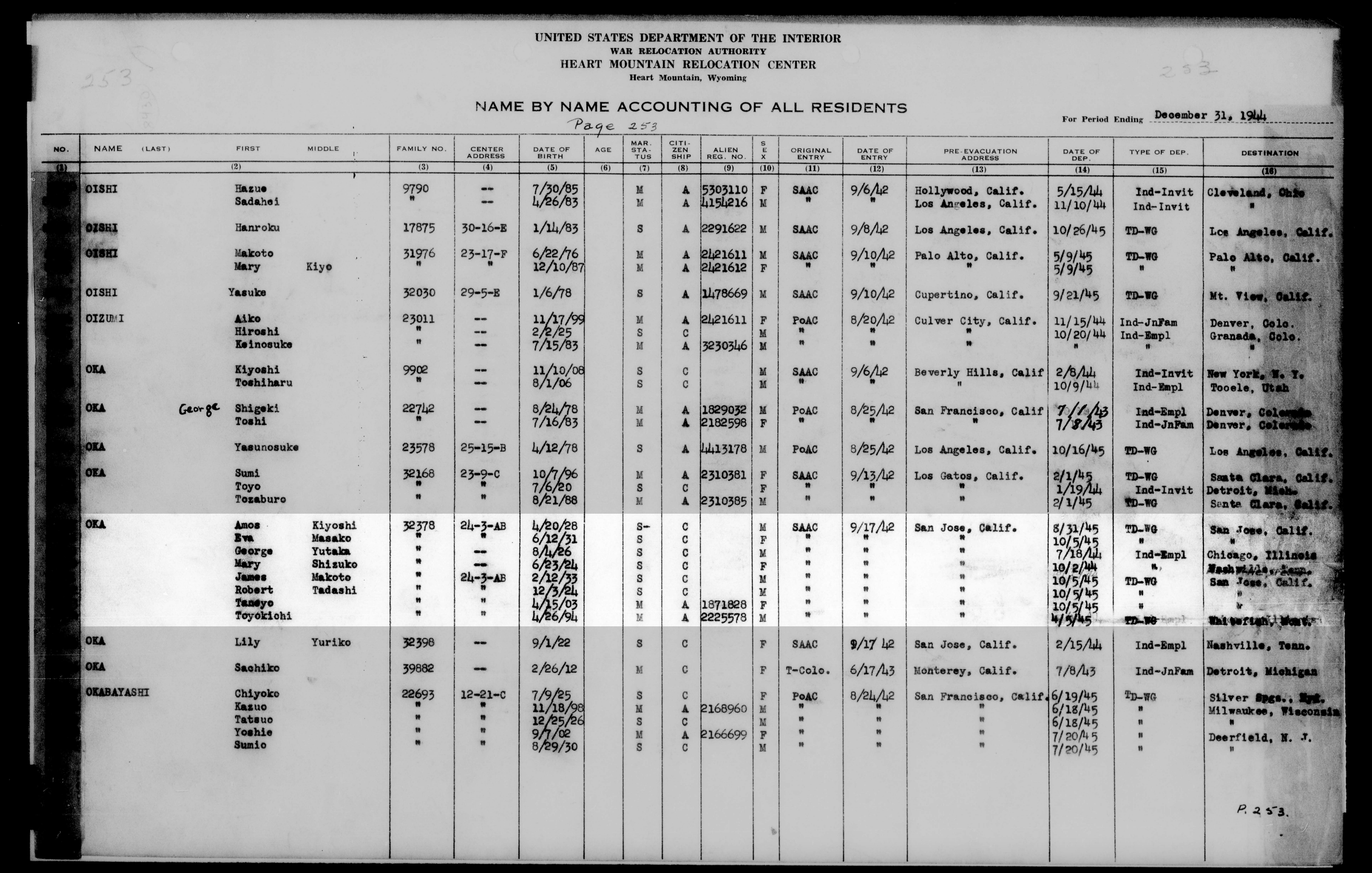

Judy Coe and her son Casey remember their ancestor Mary Shizuko Oka, who was incarcerated at Heart Mountain.

Judy Coe and her son Casey remember their ancestor Mary Shizuko Oka, who was incarcerated at Heart Mountain.

Mary Shizuko Oka was born in Loomis, CA. Her parents were small-acreage farmers who traveled from farm to farm as temporary laborers. “They didn’t have any land of their own,” Mary’s daughter Judy says. “They would just go and farm these other plots of land.” When Mary was about five years old, her family settled in San Jose, CA.

Over the years, Mary’s father was able to save up enough money to buy a truck. “I don’t know if it was a brand new truck,” Judy says. “But he was proud of it because it was his.” Shortly after, Executive Order 9066 was issued and Mary’s family was forced to leave their home—and their truck—behind. Mary was 18 years old at the time.

The second oldest out of seven children, Mary had often found herself in a caregiver role under strict supervision by her parents. “Her father […] had a very tight grip on what all the kids did,” Mary’s grand-son Casey says. “He ran a pretty tight ship.” Once she arrived at Heart Mountain, however, Mary was able to spend more time with her peers in the mess halls and neighboring barracks.

On one occasion, she and her friends convinced a guard to let them hike up to the Heart Mountain summit. “She was old enough to understand what the whole situation was,” Casey says. “But I think for her, [camp] was unusually positive, because it gave her the opportunity to find some autonomy from her parents, specifically her dad.” Mary obtained an early release from camp as part of the resettlement program and set out for Nashville, TN alone to complete her schooling. She worked as a housekeeper in Kansas City, MO for several years before returning to the West Coast. She often spoke less about the hardships of camp and more about the small triumphs—like climbing up Heart Mountain—before she passed away in 2017.

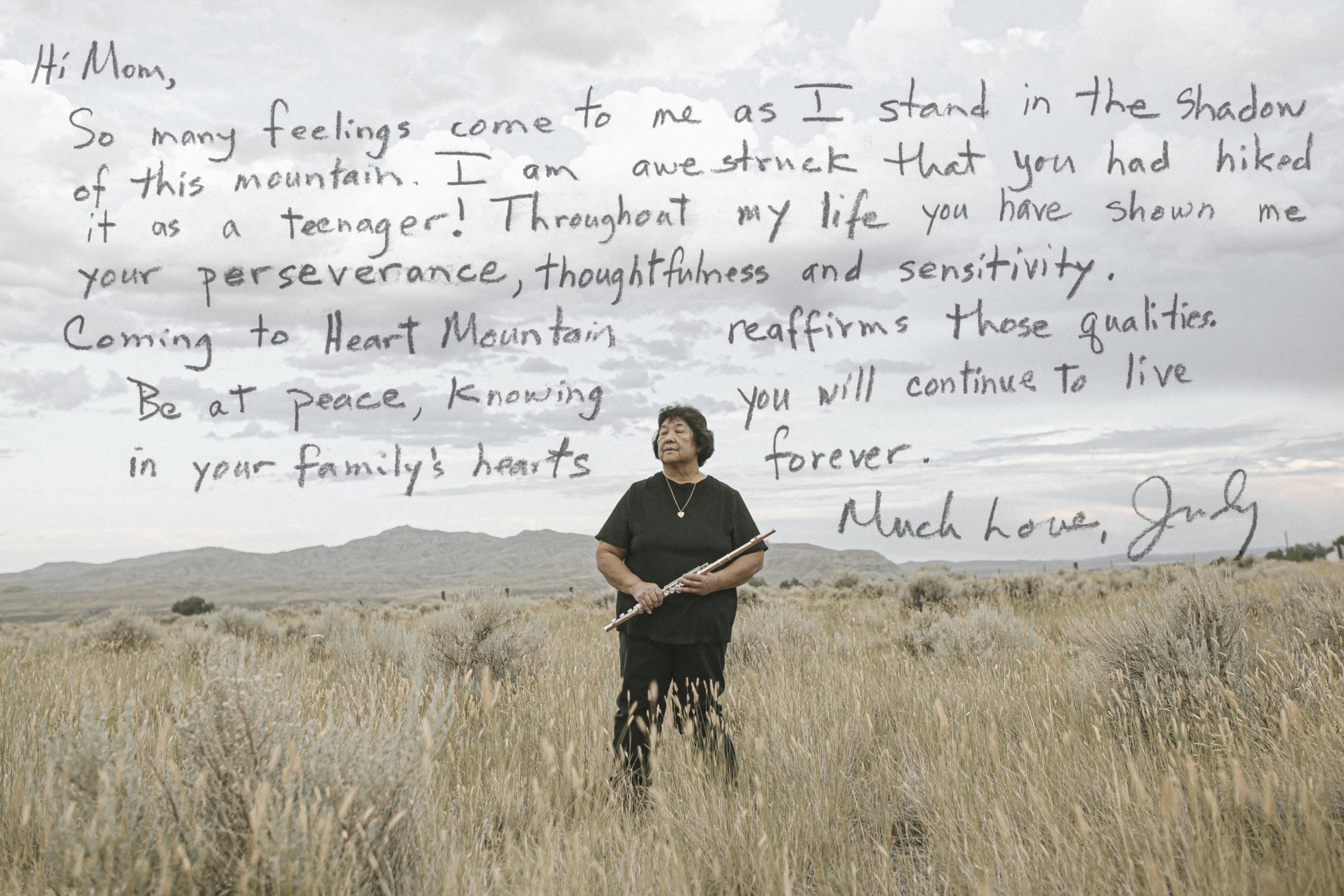

Judy Coe is the daughter of Mary Shizuko Oka. She was born in Tacoma, WA and grew up in Yuba City, CA.

Growing up, Judy had an idyllic childhood. “It was a farming community surrounded by orchards,” she says. “I remember times when we would go out on our bikes, and we wouldn’t come back until after dark during the summertime.” Still, she had limited access to Japanese culture. “I knew some people who were Japanese American kids, but I was not really close to them. We didn’t do the same kinds of things. We didn’t go to the Buddhist church,” she says. “We were secluded from people who looked like us. I jokingly say that I’m not really Japanese.”

Judy says this is in part because her parents—both of whom were incarcerated during the war—felt it was necessary to protect her and her brother from further discrimination. “[We] kind of lived in a bubble. We were totally American. We were Japanese American, but with an emphasis on the American,” she says. “They wanted us to fit in with the normal population. They didn’t want us to stand out because that’s why they were sent to camp—because they stood out.”

While studying music in college, Judy took judo, Japanese language classes, and learned how to play Japanese instruments to reconnect with her heritage. “I did all of those Japanese things, but nothing really took. So I think I was thoroughly a white American,” she says.

Judy visited Heart Mountain for the first time in 1983 and has returned with her children multiple times since then. “All the elders who were there—there’s not very many of them left. A lot of us didn’t get their story when they were alive,” she says. “I’d like to keep the connection to the Japanese American heritage with my kids.” For the 2023 pilgrimage, Judy brought her flute to dedicate a song—“Haru No Umi,” a traditional Japanese composition—in her mother’s memory.

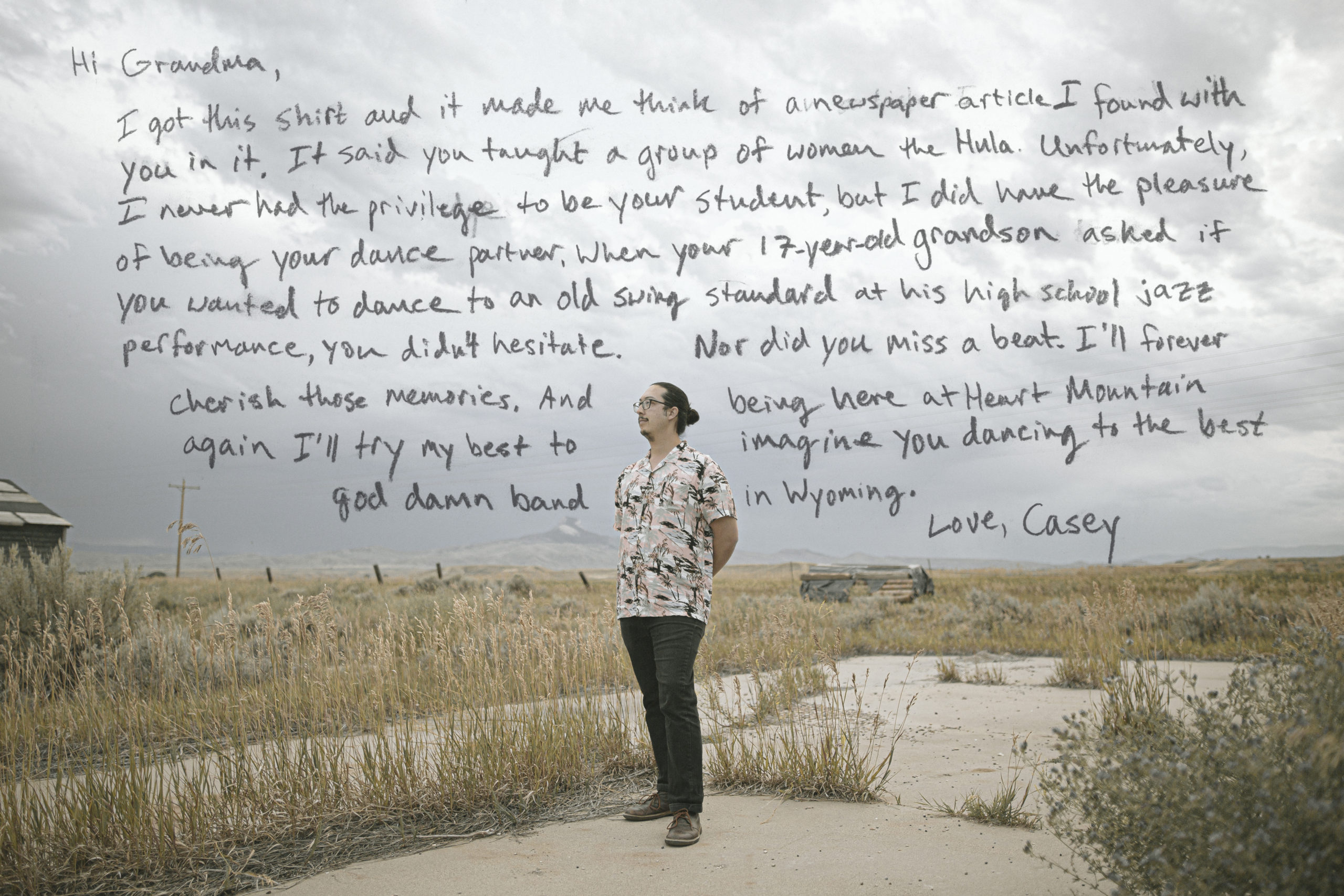

Casey Coe is the maternal grand-son of Mary Shizuko Oka. He was born in Yuba City, CA and raised in Wheatland, CA. “I think of myself as being very white in many respects, because [my] heritage wasn’t passed on to me,” he says. “You look at [other Asian] families where there’s the anecdote of ‘the classic Asian mom.’ That doesn’t really apply for me, because my mom doesn’t fit that dynamic. She was raised as a very Americanized child postwar, for good reason, given what my grandparents were trying to prevent from happening to their kids.”

In 2018, Casey, his sister and his father visited Heart Mountain and spread Mary’s ashes at the summit to commemorate her passing the previous year. He has made multiple pilgrimages to Heart Mountain since then. “Going to the pilgrimages, I’ve realized there’s probably a certain degree of intergenerational trauma that I have been able to acknowledge and kind of touch upon,” he says. “It is something that lives within me, that has been passed on to me, that is now my responsibility to try and intellectualize rather than internalize. So that we can figure out a way to rise above this.”

The pilgrimages have also been a way for Casey to honor survivors in his family who are no longer around to share their incarceration experiences. “It’s a way for us to compensate for what we didn’t get from them while they were still here,” he says. “So showing up is a way for us to show penance for what we didn’t glean from them while they were still around.”