“Growing up like I did, I was very ashamed of being Japanese.”

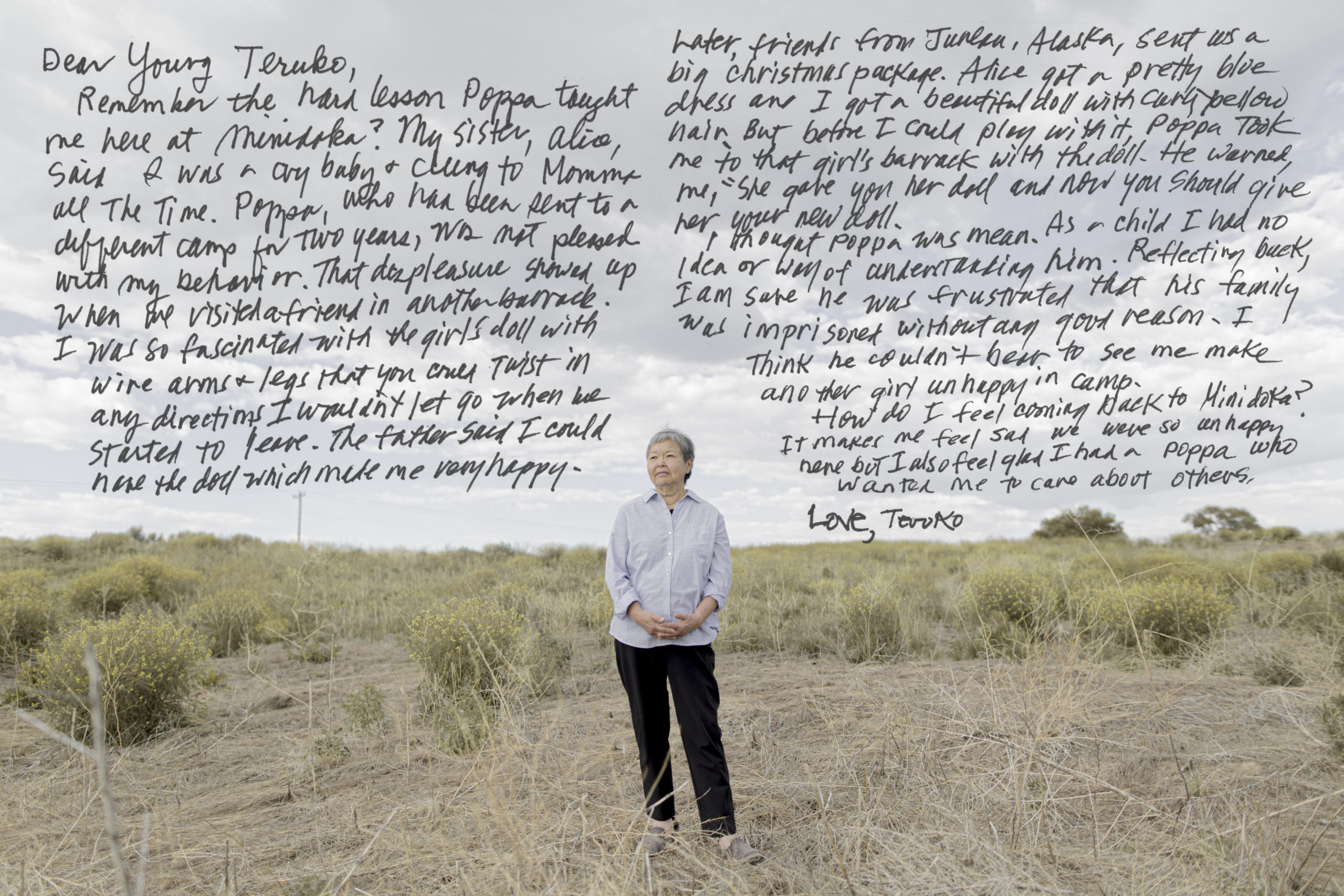

— Mary Teruko Tanaka Abo

Listen to this portrait.

Mary Teruko Tanaka Abo

Nisei

Mary Teruko Tanaka Abo was born in Juneau, Alaska. Shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the F.B.I. arrested Mary’s father—a local cafe owner—and sent him to a federal prison. “My sister remembers visiting our father in jail around Christmas time,” she says. “It was very devastating for her to see her father in jail.” Mary’s father was imprisoned in Haines and Anchorage before being transferred to Lordsburg Internment Camp and later to Santa Fe Internment Camp. Mary did not see her father again for the next two years.

When Executive Order 9066 was announced, Mary, her mother and her three siblings were sent aboard a troop ship to Seattle and arrived at Puyallup Assembly Center. Months later, they were sent aboard a train to Minidoka. Mary’s mother did not speak much English, and she feared that she and her children would be shot or left to die in the camps. “My mother started taking toast from the mess hall and hoarding it in a box underneath her cot,” Mary says. “I think she was afraid that we would be left to die in the camps.”

In the spring of 1944, Mary’s father was released from Santa Fe Internment Camp and reunited with his family in Minidoka. “He brought order to our life,” Mary says. With the head of the family returned back to safety, Mary’s older brother enlisted in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team to fight for the United States.

Once the war ended, the rest of Mary’s family moved back to Juneau to recover their cafe business. Mary recalls returning to their family home and finding that it was intact, but dirty. “People had been living in it,” she says. A neighbor offered them secondhand clothes and a place to stay while they reestablished their business.

“Growing up like I did, I was very ashamed of being Japanese,” Mary says. She recalls seeing the film Go For Broke with her mother. She was disturbed by the scenes where the 442nd Regimental Combat Team fought Japanese soldiers and refused to watch the entire movie. “I was just upset that I was there with my mother,” she says. “And when we walked home, I didn’t even want to walk on the same sidewalk as her. I wanted to separate from her. So I went to the other side of the sidewalk as we walked home. I marvel that my mother never scolded me or made me feel bad about it. She must have just intuitively felt my shame.”

Mary says her parents had a longstanding distrust of the government but also did not want to move back to Japan because of the economic devastation there. They continued to run their cafe in Juneau until her father passed away. “They weren’t going to cry over what could have been or wasn’t anymore,” says Mary. “They just kept hoping that each of their children would succeed and not have to lead a hard life like they had.”

Mary’s mother spent the rest of her days in Juneau while her children moved elsewhere. “She made apple butter. She had a cozy little pantry of food that she had. And she had a wonderful garden,” she says. “So in a way, she became the boss of her own life and her own garden. And I think she had a few good years, living life the way she wanted to.”

Mary’s information as it appears in the Final Accountability Roster for Minidoka. Courtesy of Densho Encyclopedia.

Mary’s mother Nobu (left) and Mary (right) in front of their barrack (6-4-C) in Minidoka, circa 1944. Courtesy of the Abo Family Collection.

A family portrait made in Juneau after the war. Young Mary (far right) poses with her siblings and her father Shonosuke (bottom row, left) and her mother Nobu (bottom row, right). Courtesy of the Abo Family Collection.

Mary posing with a doll at her home in Juneau about a year before her incarceration, circa 1941. Courtesy of the Abo Family Collection.

Listen to this portrait.

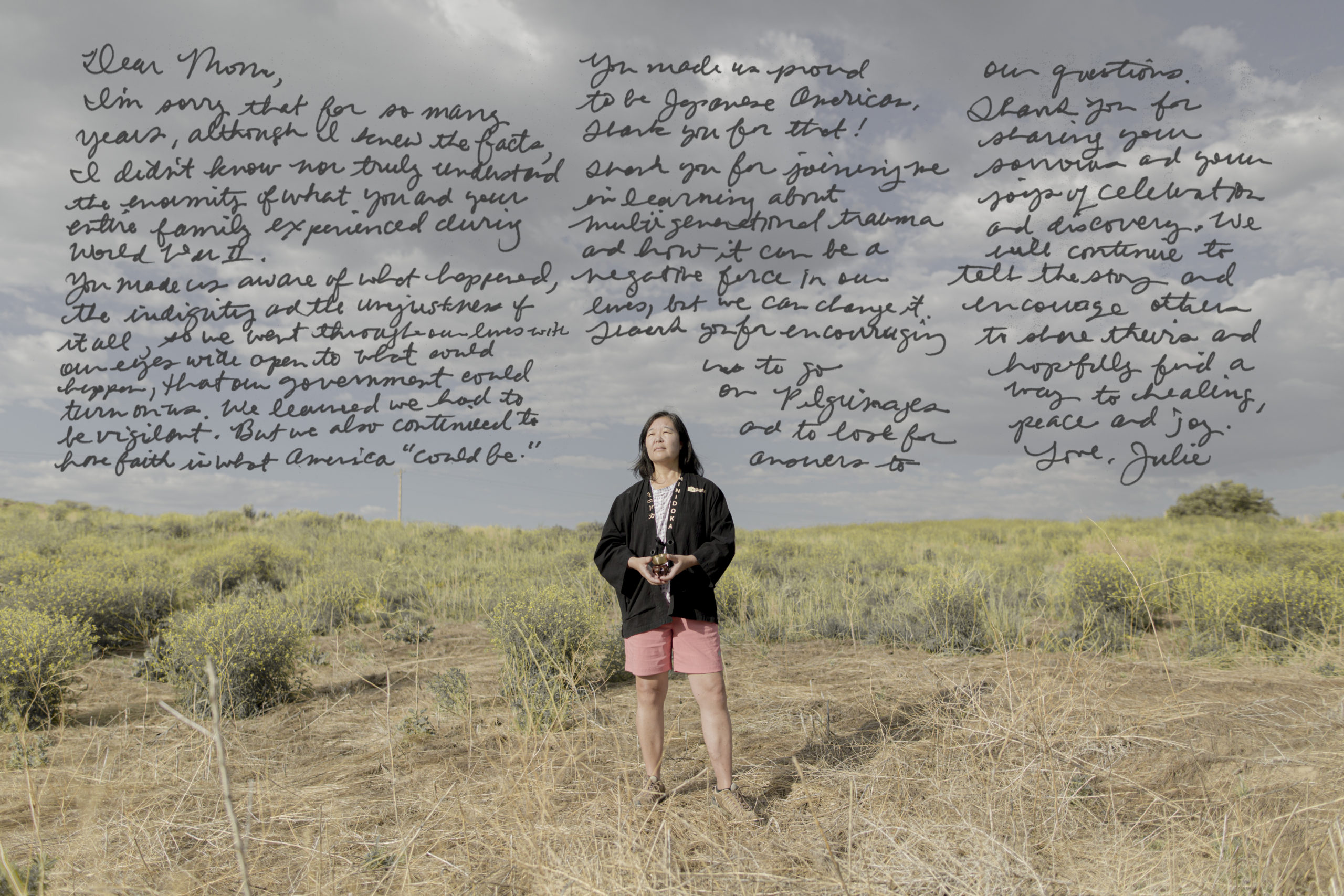

Julie Yoshiko Abo

Sansei

Julie Yoshiko Abo is the daughter of Mary Teruko Tanaka Abo. She was born in Bremerton, WA.

Growing up, Julie says her mother encouraged her to be proud of her Japanese American heritage. “When I was in kindergarten, there was a form that I had to fill out,” she says. “I remember her distinctly saying, ‘Write Japanese American in there. We’re proud Japanese Americans.’”

It wasn’t until Julie was an adult when her mother shared with her a paper that she had written back in college about how ashamed she used to be of her Japanese heritage. “I remember the last line was, ‘I don’t want to be a dirty jap. That was the last line,” she says. “I was just heartbroken. But at the same time, I wanted to tell her that she gave me a gift because I felt very free to be who I am.”

Since she was a child, Julie remembers her mother and her siblings speaking about their incarceration during family reunions. “The elders would be talking at night around the table,” she says. “But it was more like talking about the facts. Historical facts.” She says her mother only began to reveal more personal details about her incarceration after they attended their first pilgrimage together in 2015.

Julie has worked as an English educator over the past two decades. After volunteering on the exhibit “Righting a Wrong: Japanese Americans and World War II” at the Smithsonian Museum in 2016, she was inspired to educate the public on her family’s incarceration. Julie was previously the Director of Washington Affairs at the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation, and she currently works as a freelance public historian.

“I remember the last line was, ‘I don’t want to be a dirty jap.’ That was the last line. I was just heartbroken.”

— Julie Yoshiko Abo

Listen to this portrait.

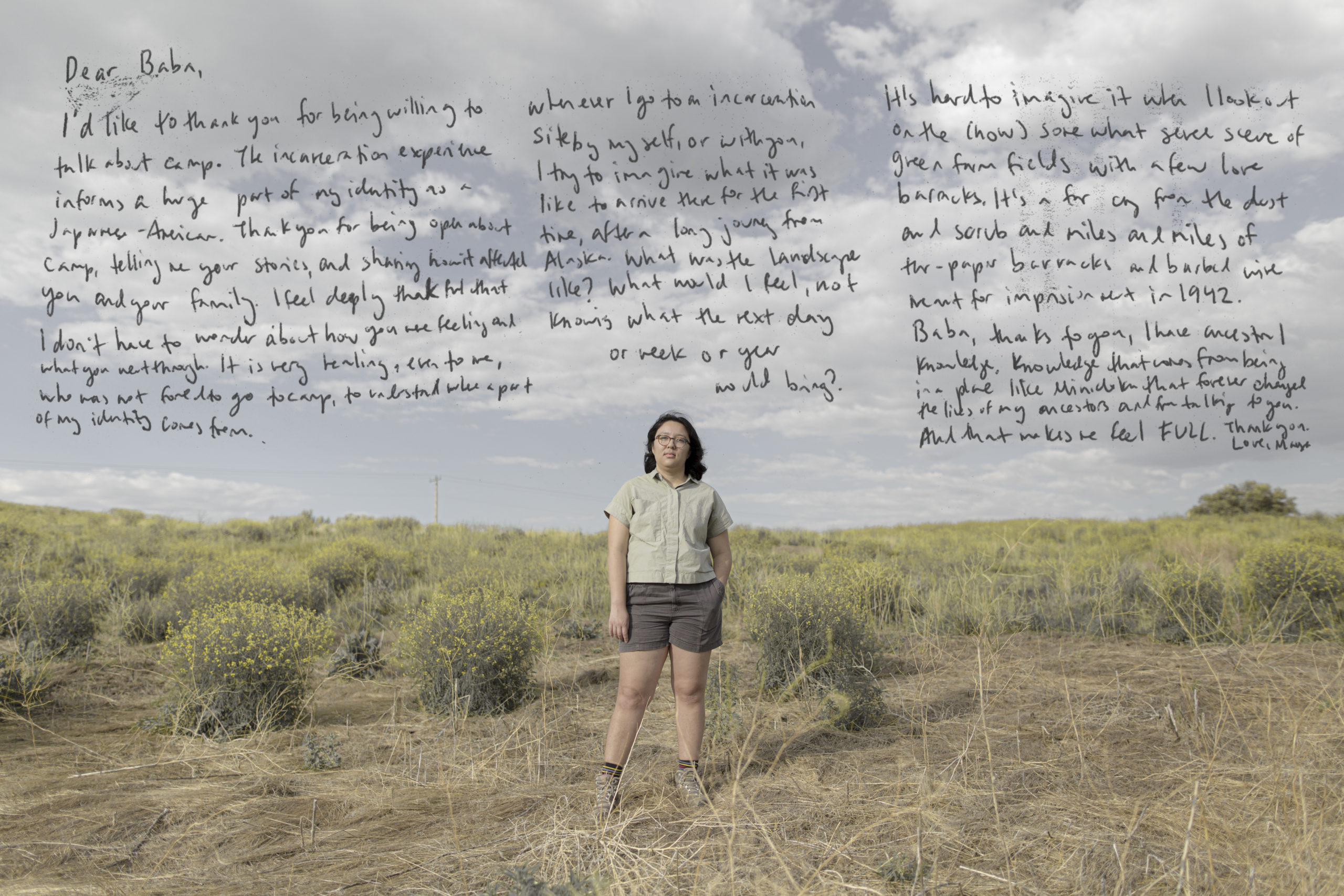

Maya Abo Dominguez

Yonsei

Maya Abo Dominguez is the maternal grand-daughter of Mary Teruko Tanaka Abo. She was born in Oakland, CA.

Born to a Japanese American mother and a Mexican American father, Maya did not know many others—aside from her sister—who were of mixed heritage. “I thought we were the only ones in the entire world,” she says. “I think there’s definitely that aspect of feeling like an outsider or having to defend my American identity.”

Although Maya had heard stories about her family’s incarceration since she was a child, the story that stood out to her most was that of her great-grandmother hoarding bread crusts and tins from the mess hall in fear of starving to death. “That really hit me – how scary and what an intense experience that was,” she says.

Maya describes her grandmother as a community builder who speaks freely with the people around her. “She’s very outspoken. She’s not afraid to speak up when she thinks something is wrong,” she says. “She has a strong sense of justice, which I think I have inherited.”