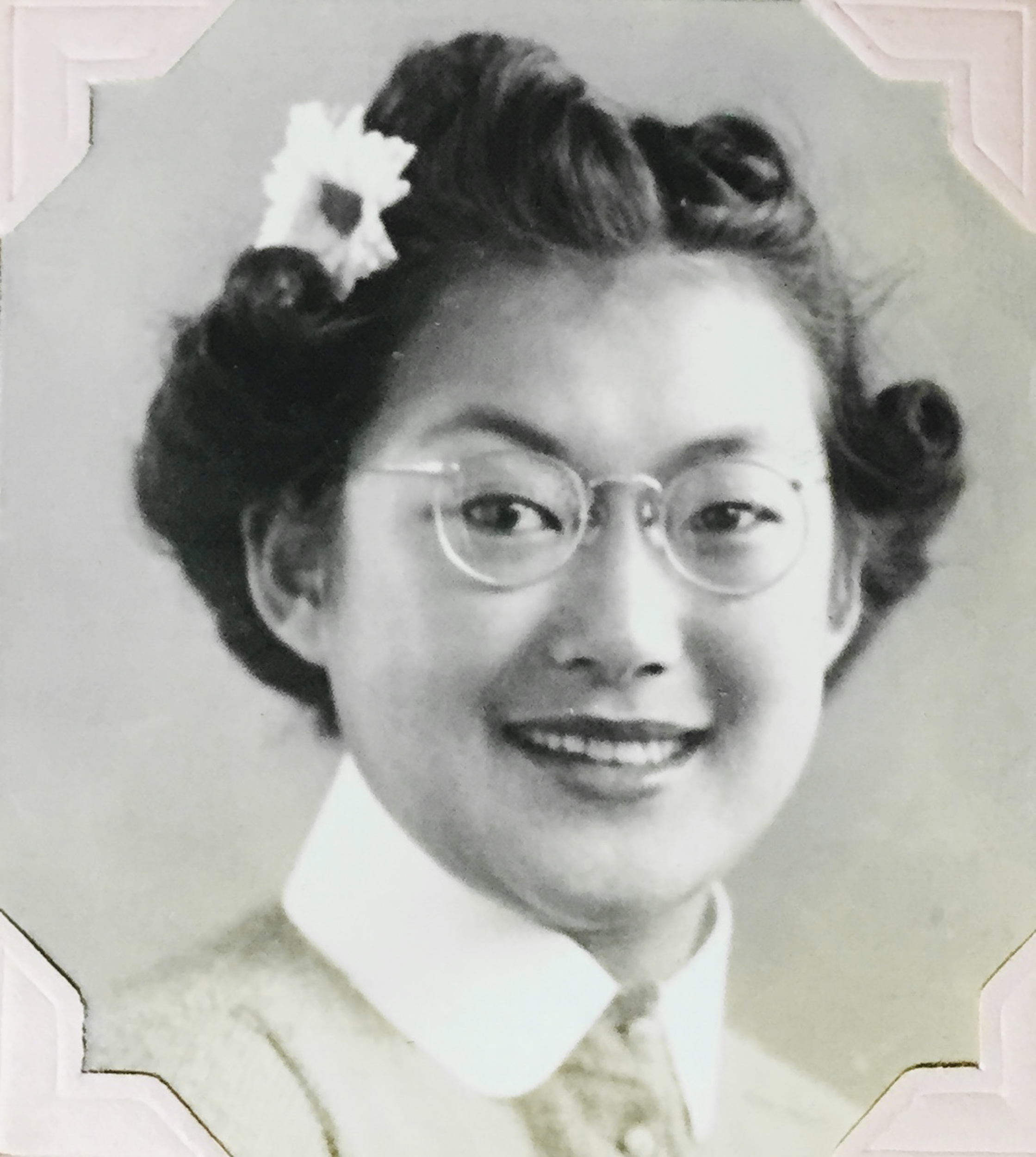

“It makes me sad and angry now to think that I directed my anger at my father, instead of to the true villain, the U.S. government.”

— Fumiko “Fumi” Takayanagi

Fumiko “Fumi” Takayanagi

Nisei

Fumiko Takayanagi—who went by Fumi—was born in Oakland, CA between two Issei parents.

When Fumi was 14 years old, she and her younger brother joined their mother on a trip to Japan. One night, Fumi was sleeping in their relatives’ home in Shizuoka Prefecture. “Her mother came to her in a dream that night,” says her daughter Nancy. “She said, ‘Fumiko, come with me’ and [Fumi] was like, ‘No, I don’t want to. I want to stay.’ And then her mother said goodbye to her.” The next morning, Fumi woke up to news that her mother had committed suicide. A month later, her brother and she returned to the United States.

Fumi’s family lived in Berkeley on the north side of University Avenue. Fumi’s father Tokutaro owned a flower nursery across three parcels of land. A few months before Executive Order 9066 was issued, the north side of University Avenue became a restricted zone. Tokutaro was unable to return home to his children. He stayed with friends on the south side of University Avenue while he worked out of a parcel of his nursery that was outside of the restricted zone. “He could not cross University Avenue without being arrested,” Fumi stated in a testimony that she presented to a community forum in 1981 as part of the Redress Movement. “My younger brother packed a lunch for my father and took it to him at noon each day.”

Meanwhile, Fumi was studying art in Los Angeles. Fearing that her family would be split into different camps, she put her studies on hold and returned home to Berkeley. Soon after, Fumi’s family was sent to Tanforan Assembly Center—where they lived in horse stalls—and was later transferred to Topaz. “I get angry when I think about the allergic reaction I had to the horse manure of the Tanforan horse stalls,” Fumi stated in the testimony. “My face broke out in a rash, which did not heal due to constant scratching, and it was compounded later by the dust and heat of the Topaz desert.” She also recalls getting sick from the food in the mess hall and waking up multiple times in the night to walk to the communal bathrooms.

In 1943, Fumi was offered an early release from camp if she agreed to live under the aegis of Robert Platt, a geography professor, and his family. The Platt family decided to sponsor Fumi and her friend at their Chicago home despite protests from their neighbors saying that they would be “killed in their sleep” and that “the Japanese would run amok in the area,” according to Fumi’s testimony. “That changed her whole view of white people,” says Nancy. “She named me after the Platt’s daughter, and my sister after Harriet Platt. My brother’s middle name is Robert.”

Inspired by her sponsor, Fumi went on to study cartography and applied for a government job in Washington, D.C. As part of her security clearance, she was interrogated by a group of F.B.I. officials. “One official angrily stated that my younger brother Tadao had made a remark in Topaz to the effect of ‘To Hell with the United States,’” she says in her testimony. “I stated that I could not be responsible for my brother’s remarks.” She also recalls another official asking her about a portrait of Emperor Hirohito on the east wall of their living room—a detail about her family home that she suspected was obtained through surveillance.

Throughout her testimony, Fumi lamented directing her anger at family members during and after their incarceration. She was upset with her brothers for serving in the U.S. military after being held in the camps. She was distrustful of her friends and neighbors, whom she thought may have revealed details about the Emperor Hirohito portrait to the F.B.I. She was angry with her father for taking up precious luggage space to bring eucalyptus leaves—a reminder of their life in Berkeley—to Tanforan Assembly Center and Topaz. “It makes me sad and angry now to think that I directed my anger at my father, instead of to the true villain, the U.S. government,” she said.

Fumi eventually returned to Berkeley to study geography. There, she married a Japanese American man with whom she bought a home in the “flats of Berkeley”, an area where Japanese Americans were not subject to redlining. Over the years, she raised three children. Once they were grown, she became a necklace designer and sold and exhibited her work internationally. “She designed necklaces using ojime and netsuke,” Nancy says. “So in the end, she did return to art.” Fumi rarely spoke about the hardships of her incarceration with her children until she passed away in 2003.

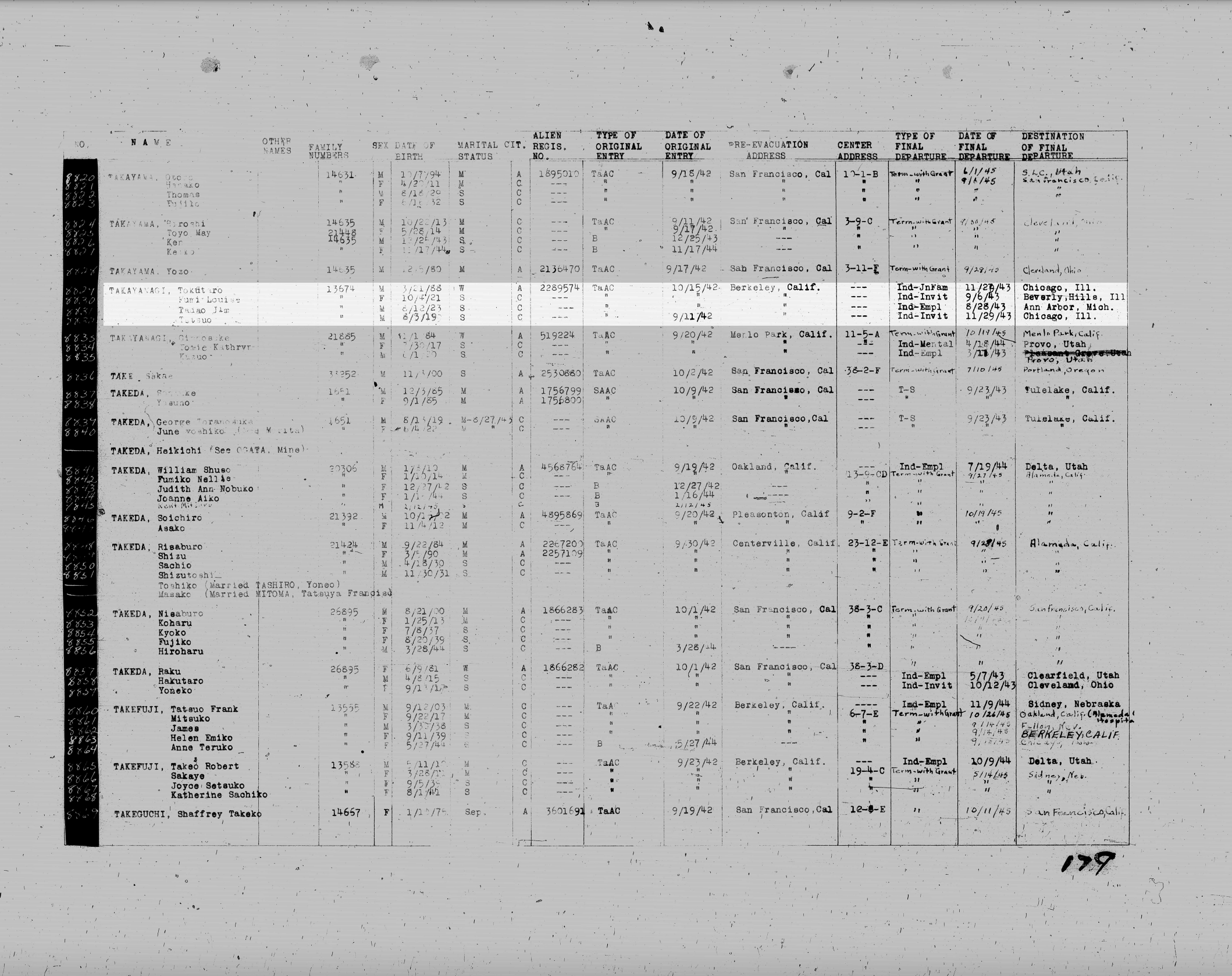

Fumi’s information as it appears in the Final Accountability Roster for Topaz. Courtesy of Densho Encyclopedia.

Listen to this portrait.

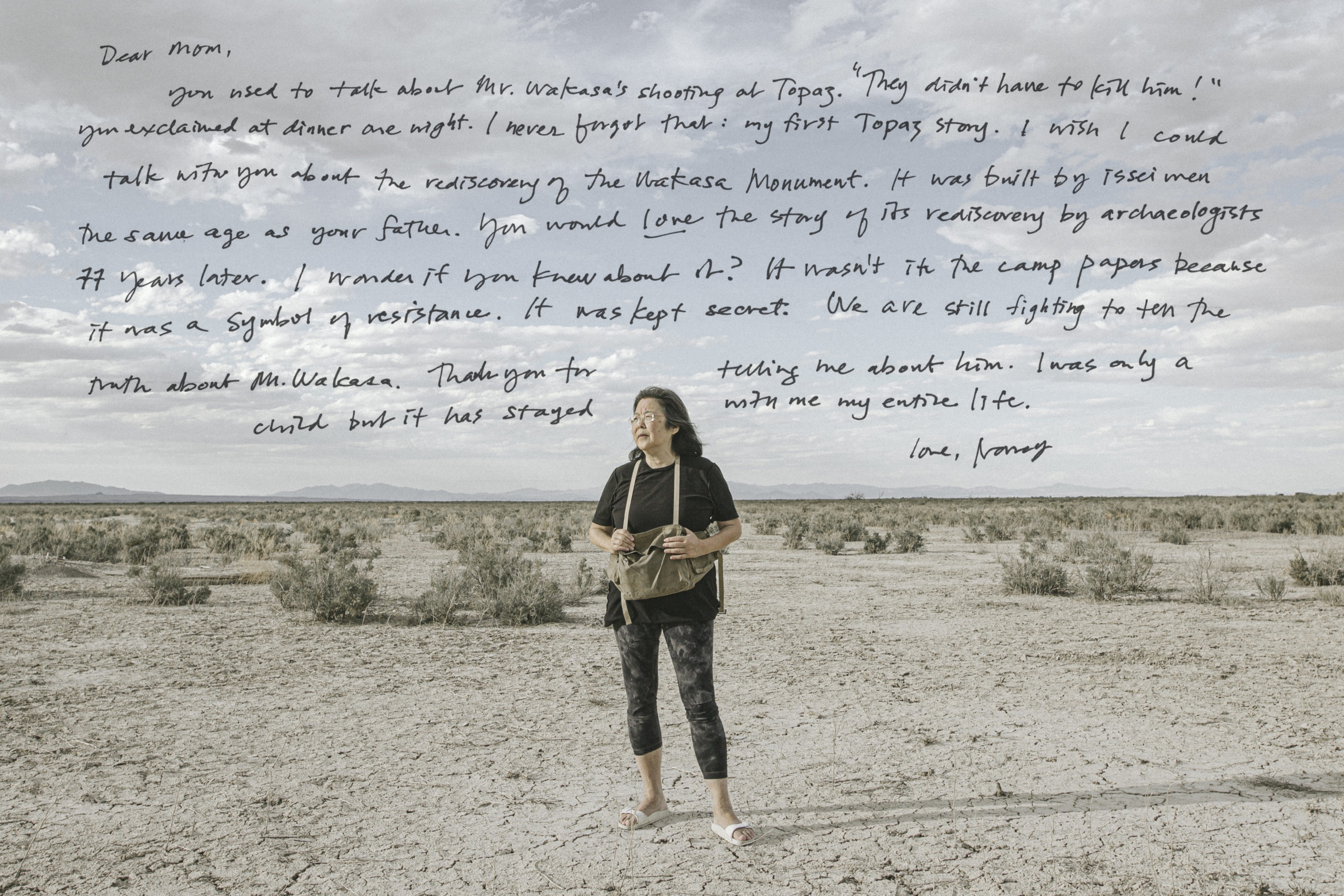

Nancy Hana Ukai

Sansei

Nancy Hana Ukai was born and raised in Berkeley, CA. She is the daughter of Fumiko “Fumi” Takayanagi.

Nancy first became aware of her family history in elementary school when her mother spoke about the murder of James Hatsuaki Wakasa at the dinner table. “She was normally such a happy and funny person who read a lot and was always thinking about art and social issues,” says Nancy. “Her anger and outrage and grief at that moment really struck me as a little kid.”

Upon graduating college, Nancy decided to move to Japan on a Fulbright English Fellowship. After completing the fellowship, she became a weaving apprentice and lived in a Buddhist temple in Toyama Prefecture for a year. She then moved to Tokyo and worked as a journalist for Asahi Shimbun, the Tokyo bureau of Newsweek and other publications. “I think that for a long time I had denied […] or suppressed that part of my identity,” she says. “And then I kind of went to the other extreme to learn Japanese and stayed there.” After 14 years of living in Japan, Nancy returned to the United States in 1990.

In 2015, Nancy came across an advertisement for an auction to purchase Japanese American camp artifacts. “It was published […] as a rare opportunity to buy internment camp art,” she says. “And I thought, well, that’s weird.” This prompted Nancy to lead a social media protest to stop the auction and to begin 50 Objects, a digital project that preserves the personal stories behind camp artifacts. Aside from serving as the project director of 50 Objects, Nancy works as a freelance writer, researcher and a founding member of the Wakasa Memorial Committee.