Sunahara Family

Heart Mountain

Carol Sunahara and her grandchildren remember their ancestor Dorothy Haruko Nagai, who was incarcerated at Heart Mountain.

Carol Sunahara and her grandchildren remember their ancestor Dorothy Haruko Nagai, who was incarcerated at Heart Mountain.

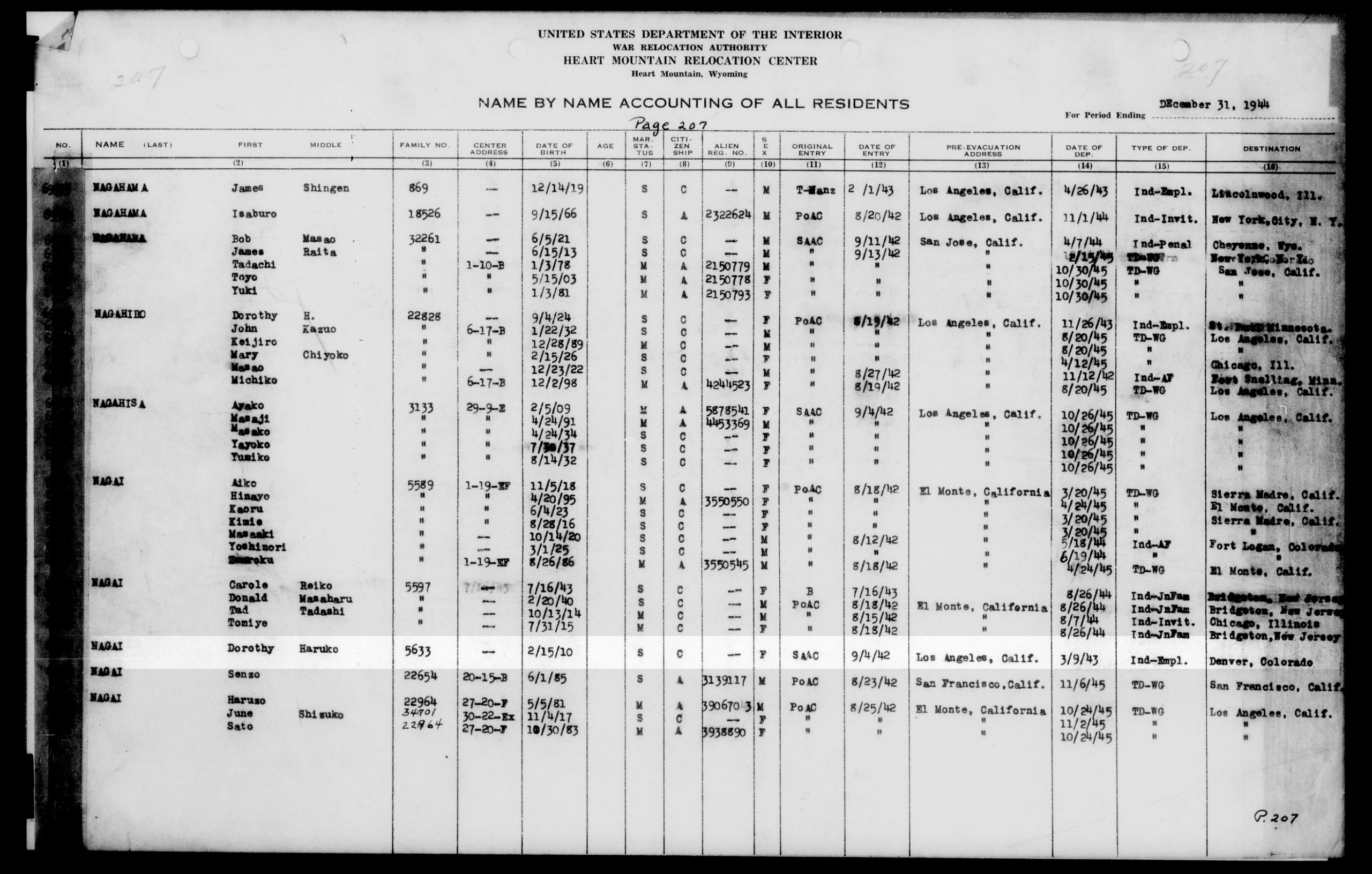

Dorothy Haruko Nagai was born in Helemano, HI. Her exact date of birth is unknown because she was born on a plantation in rural Oahu where birth records were not regularly kept. When Dorothy was 10 years old, her father died from the Spanish flu, leaving her mother to look after her sister and her singlehandedly.

When Dorothy turned 18, she moved to Los Angeles in search of economic opportunities. She worked as a geisha at a teahouse in East Los Angeles and sent remittances to her family. Her mother and sister joined her in the mainland for a brief period, but they decided to return to Hawai’i, fearing the deportation of her mother—a non-citizen—amidst rising anti-Asian sentiment. Shortly after, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066. Dorothy, now alone on the mainland, was sent to the Santa Anita Assembly Center before she was transferred to Heart Mountain.

After her release, Dorothy took on an array of jobs—from nannying in New York City to working as a seamstress in Los Angeles— and continued to send money and gifts to her family back in Hawai’i. Dorothy spent the rest of her years living in a small studio apartment in Los Angeles and rarely spoke about her incarceration until she passed away in 1990.

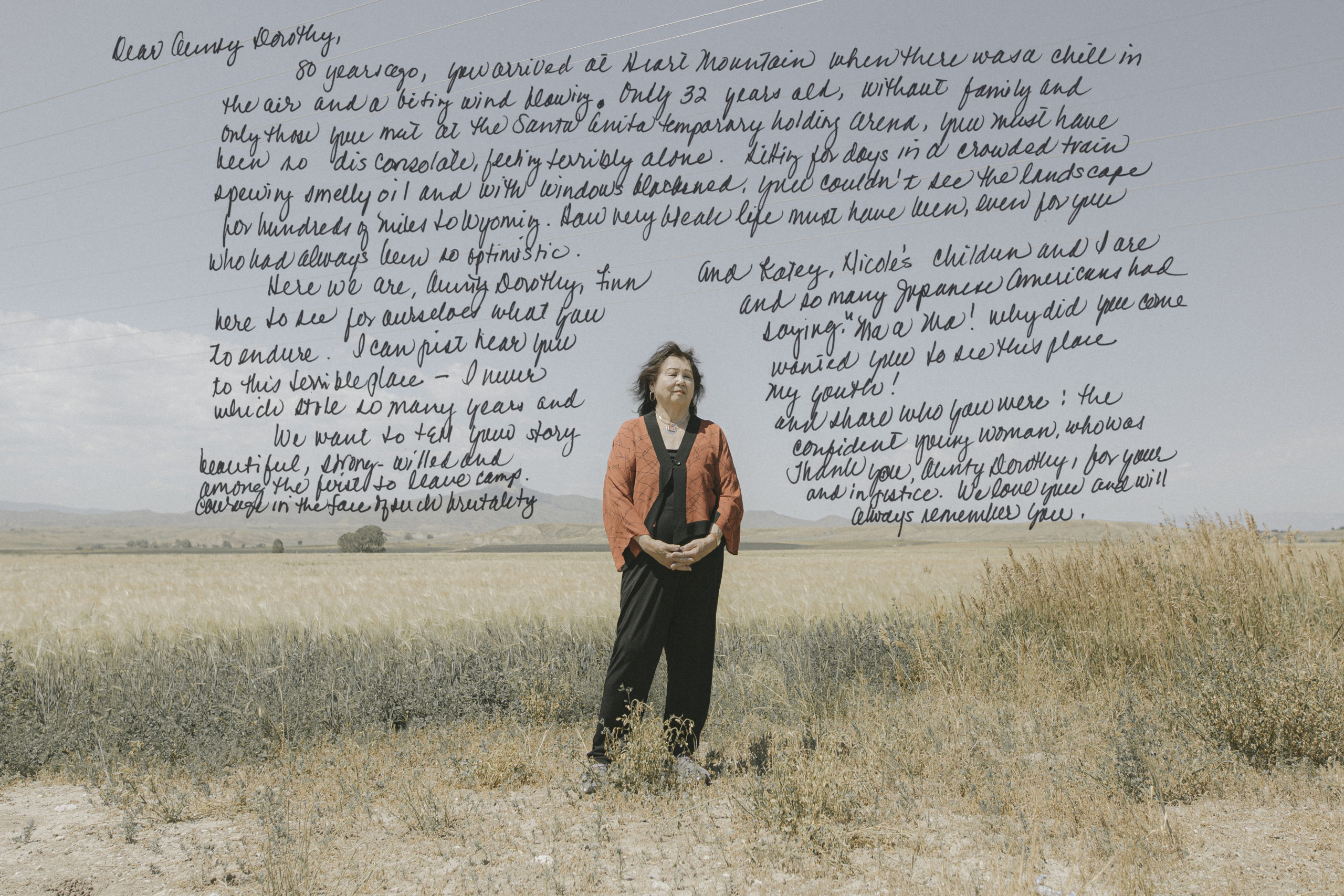

Carol Sunahara is the maternal niece of Dorothy Haruko Nagai. She was born in Los Angeles when her parents and grandmother— originally from Hawai’i—briefly joined Dorothy on the mainland to seek economic opportunities. They decided to return to Hawai’i shortly before the war and as a result, narrowly escaped the mass incarceration.

Following the Pearl Harbor attacks, Carol was required to wear a gas mask to school, and there were regular blackout drills in the evening. “I think that the Americans in Hawai’i were very much afraid of an invasion,” she says. “But we were never made to feel that we were the enemy.” People of Japanese descent made up a larger portion of Hawai’i’s total population—about a third—and were mostly exempt from Executive Order 9066 except for select religious and community leaders.

When Carol was 17, she wanted to attend university on the mainland. She decided to visit Dorothy in Los Angeles and spend the summer with her. During their time together, however, Dorothy encouraged her to dress differently and mask her Hawai’ian Pidgin accent. “I thought, this is ridiculous. I can’t live like this.” After that summer, Carol opted for a university in Hawai’i instead.

Carol says Dorothy did not share much about her incarceration. “I suspect that there was residual anger about it throughout her entire life,” she says. After spending her adult years in both Hawai’i and the mainland, Carol eventually decided to move back to Hawai’i to raise her own children. “I did not want my children to grow up as a minority,” she says. “And I’m very glad that I did because I have four very confident [daughters] who are very independent and very outspoken and articulate. They’re very proud of who they are.”

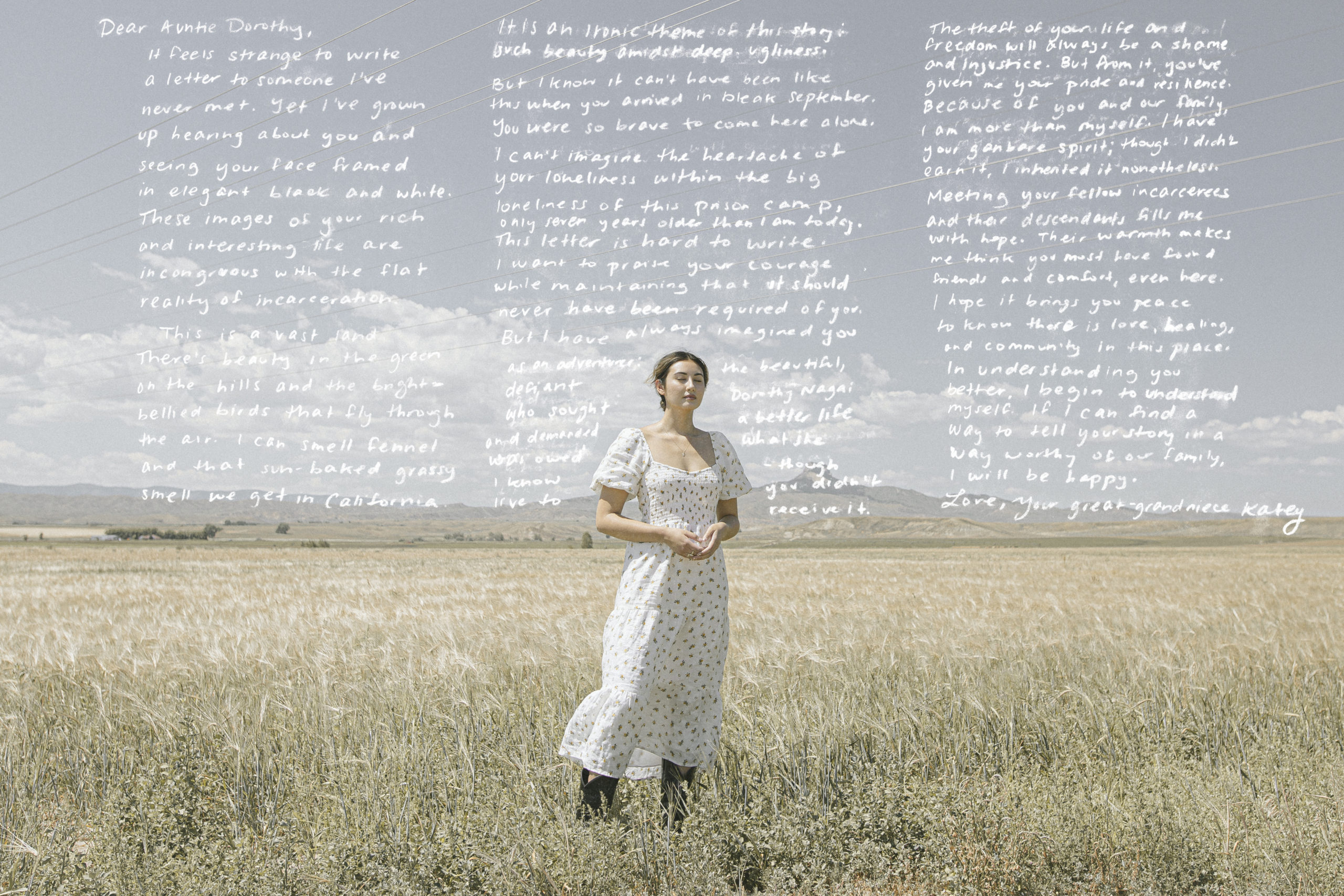

Katey Terumi Laubscher is the maternal grand-niece of Dorothy Haruko Nagai. She was born in Redwood City and currently lives in New York City.

Katey says her upbringing on the mainland was different from that of her family members in Hawai’i. “Growing up in Hawai’i, mostly everybody is Asian, or Hawaiian,” she says. “So it’s a really different upbringing and outlook, versus when you grew up on the mainland, being in the minority.” When Katey was called a racial slur by a couple of classmates after a class discussion about the Pearl Harbor attacks in the fourth grade, she felt ill-prepared to respond. “I just remember feeling angry and confused because I knew there was nothing I could say back to them that equated to what they said to me,” she says. “I think the benefit a lot of people have growing up in Hawai’i is that they can feel like individuals. They don’t have to be put in that box that people often put minorities in on the mainland.”

During this encounter, Katey also realized that her perceptions of the Pearl Harbor attacks were different from that of her mainland peers. “I think the way I went about Pearl Harbor was that it was an attack on Hawai’i, and so my family, they were the people being attacked,” she says. “And that’s why it was so strange to go to school and be called [a racial slur] because [even though] my family is Japanese, they were not the ones attacking Pearl Harbor.”

Katey says stories about Dorothy typically center on her beauty and adventurous personality—her incarceration rarely comes up— and that they often have a “legendary aspect” to it. “We have a lot of ghosts in my family lore,” she says. “And I think there’s the positive and that there’s also the negative, where these [ghosts] have long shadows.” Katey hopes visiting Heart Mountain will help her better understand the contours of her family history. “I think there’s a lot of guilt I feel being Japanese, but also not speaking Japanese, and not fully understanding our family history in detail,” she says. “I have this dual identity where I’m markedly different from a white American, but I don’t have an instant connection to what makes me different. I haven’t had all of the hardships that Issei had. I’m so far removed in many ways from the experiences of my ancestors who first came to the US. So I think that’s where [the guilt] comes from.”

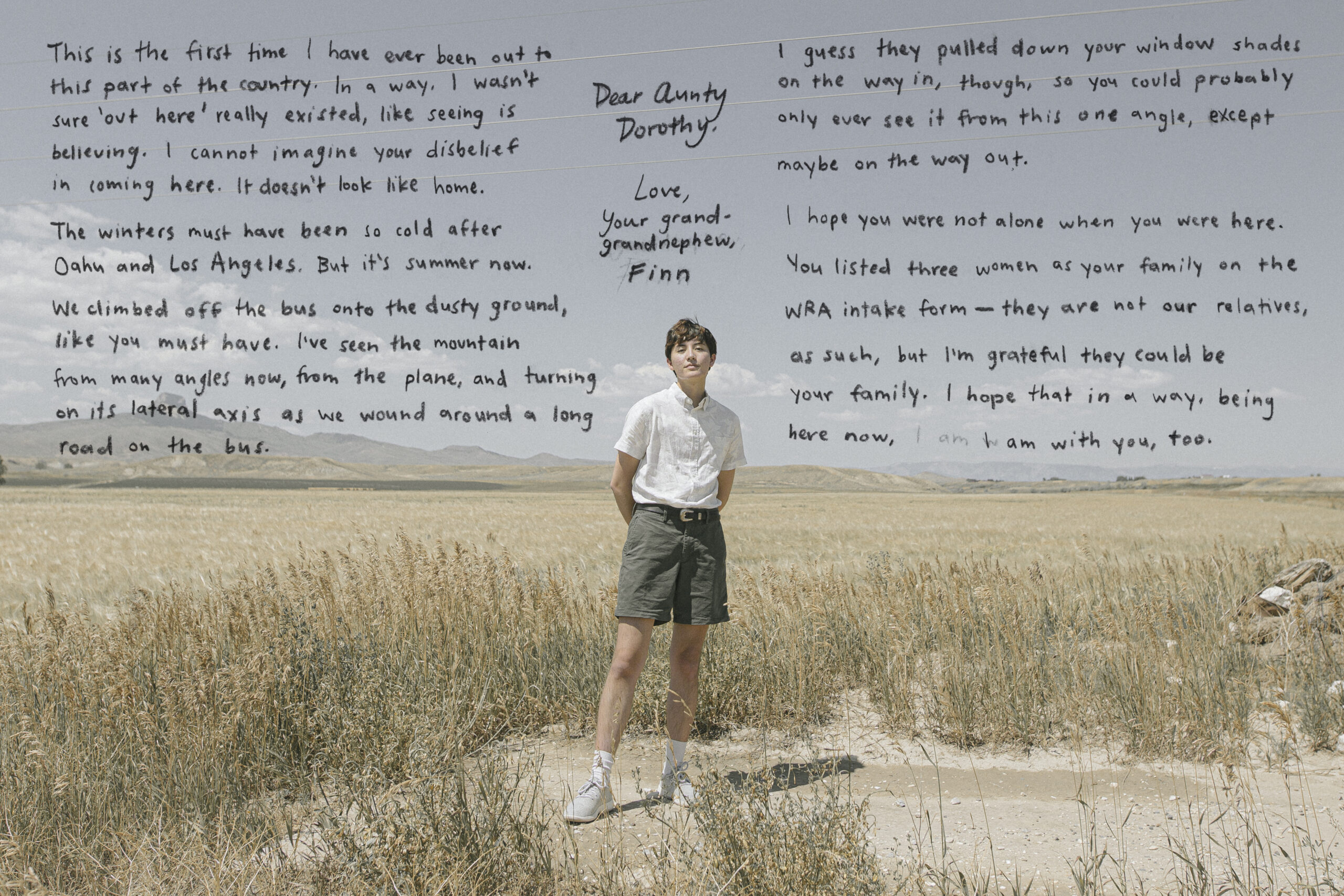

Finn Laubscher is the maternal grand-nephew of Dorothy Haruko Nagai. He was born in Redwood City and currently lives in San Francisco. Finn first learned about Dorothy’s incarceration when his mother shared that a pair of traditional Japanese dolls in their home was one of few personal items that Dorothy was able to salvage after her incarceration.

Growing up, Finn didn’t know many Japanese Americans, let alone mixed heritage Japanese Americans with roots in Hawai’i. “I have a bit of imposter syndrome when it comes to being Japanese American,” he says. “On my grandmother’s side, we’re Gosei; on my grandfather’s side, we’re Yonsei. So very removed from Japan itself.”

Still, he could trace a few cultural values that were passed down multi-generationally, including the emphasis on having a refined appearance. “One of the only Japanese words that I knew growing up was oshare,” he says. “It’s the way you carry yourself and the idea of looking very neat and trying to keep everything in its place that definitely carried down through the generations.”