“My father was the Chief of Police in Camp I. He had a very challenging job—there were family arguments, juvenile delinquents, and there were also suicides. He had to cut down somebody that hung themselves.”

— Marlene Shigekawa, on her father

Kiyoshi Shigekawa

Nisei

Kiyoshi Shigekawa was born in Los Angeles between two Issei parents. Before he entered kindergarten, Kiyoshi’s family moved to Anaheim, where he spent the rest of his childhood and young adulthood. “He played football in Anaheim High School,” his daughter Marlene says. “He was kind of like a John Wayne. He was tall and big and joked a lot. He was a leader.”

After college, Kiyoshi worked as a commercial fisherman and split his time between Anaheim and San Pedro. He met his wife Misako on Terminal Island, where her family ran a drug store. They were married in June of 1941. Shortly after, Pearl Harbor was attacked and Executive Order 9066 was issued. “Because Terminal Island was next to a naval air station, they had 48 hours to leave,” says Marlene. Left with little choice, Kiyoshi and Misako temporarily settled in Anaheim before they were sent to Poston a few months later in May of 1942.

When the couple arrived in Poston, many of the barracks were incomplete or hastily built. “My mom was six months pregnant when they came to camp,” says Marlene. “She was so thirsty, but when they got off the train and she drank the water, it was muddy because the pipes were just installed.” The barracks were made of green lumber that shrank over time, leaving large knot holes that let plumes of dust blow into the incarcerees’ living quarters. “They used tops of tin cans and tarp to cover the knotholes,” says Marlene. Frequent dust storms also blew the roofs off some barracks.

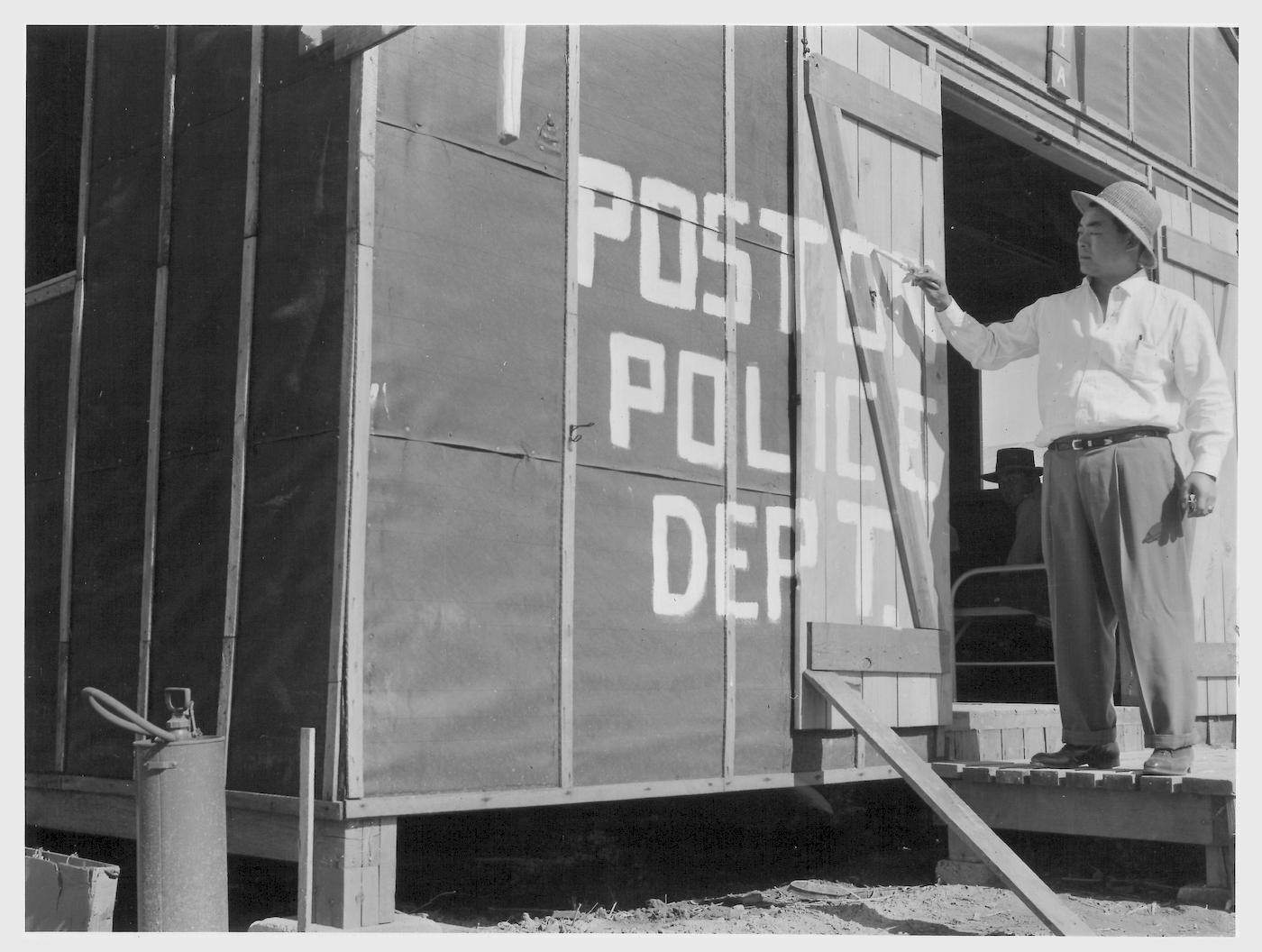

“My father was the Chief of Police in Camp I,” says Marlene. “He had a very challenging job—there were family arguments, juvenile delinquents, and there were also suicides. He had to cut down somebody that hung themselves.” Kiyoshi and Misako had their son Gerald in August of 1942, and their daughter Marlene two years later—both in Poston.

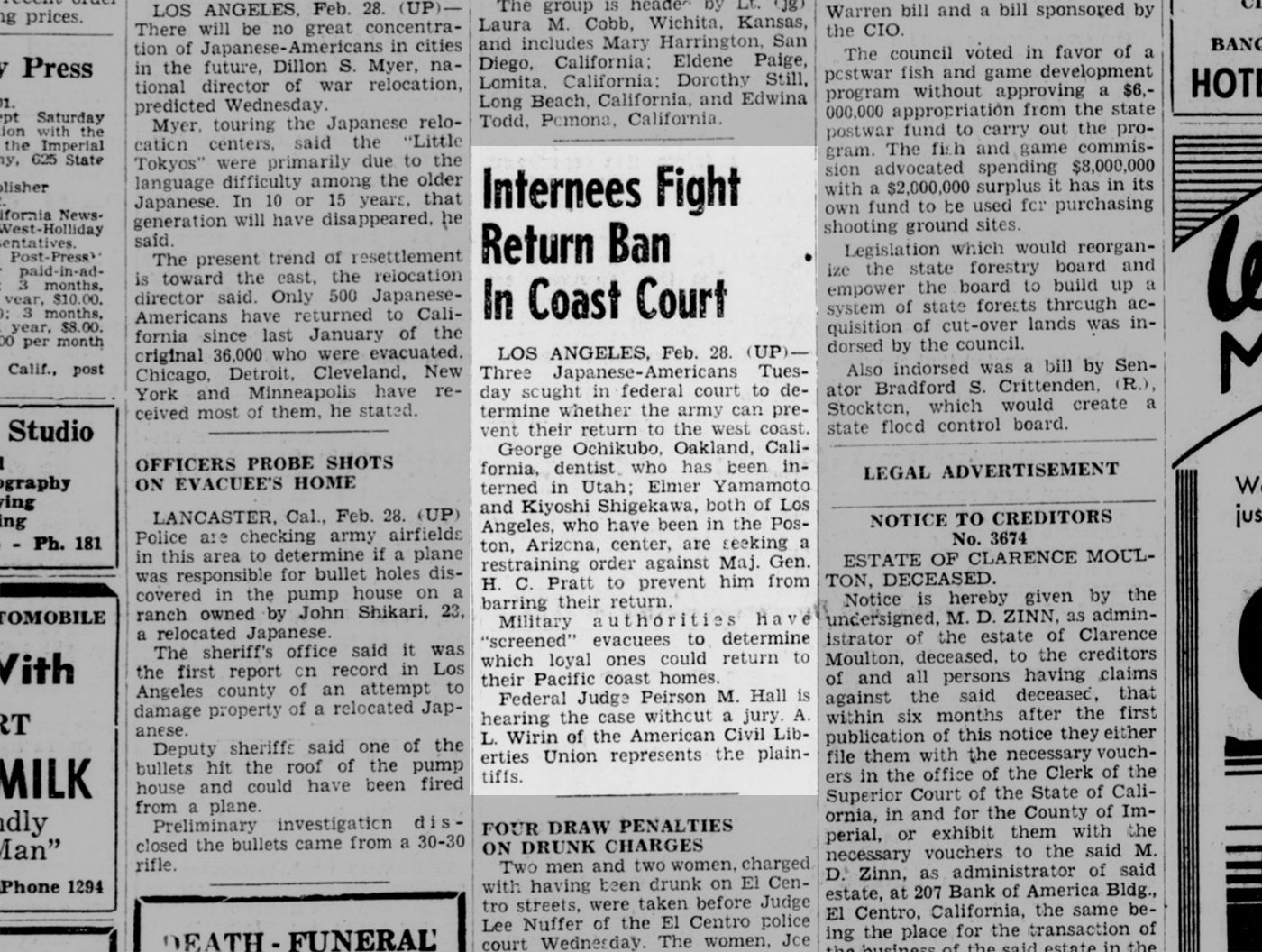

In February of 1945, Kiyoshi and two other incarcerees worked with attorney A.L. Wirin from the American Civil Liberties Union to seek an injunction against military authorities who subjected them to civilian exclusion orders that prevented their return to the West Coast. The judge upheld the exclusion order, and Kiyoshi was unable to leave Poston. In September of 1945, they were able to return to his family’s orange grove in Anaheim, which they had left in the care of their white neighbors before they were forced to leave for camp. Kiyoshi, Misako and their children moved into a small home on the grove with other family members while they got back on their feet. “It was really tiny, probably 800 square feet,” says Marlene. “There were 10 people living there.”

Over the years, Kiyoshi worked his way up from hauling oranges to working as an aerospace engineer. He rarely spoke about his incarceration until he passed away in 1998.

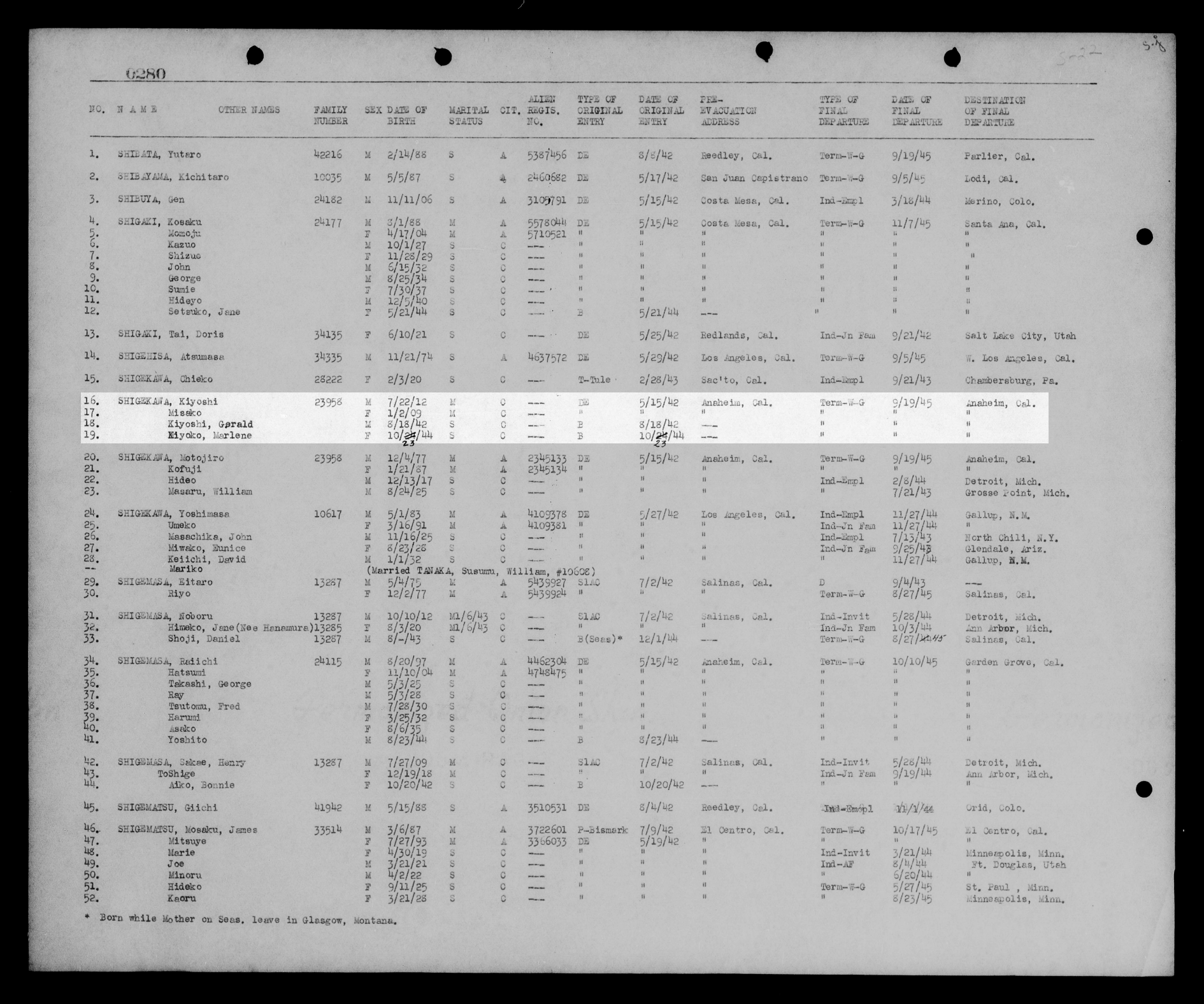

Kiyoshi’s family information as it appears in the Final Accountability Roster for Poston. Courtesy of Densho Encyclopedia.

Kiyoshi painting the sign on the first police station in Poston, circa 1942. Courtesy of the Shigekawa Family Collection.

A 1945 article in the Imperial Valley Press about Kiyoshi and two other Japanese American incarcerees seeking an injunction against Major General H.C. Pratt, who barred their return to the West Coast, dated 28 February 1945. Courtesy of UC Riverside California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Listen to this portrait.

Marlene Shigekawa

Sansei

Marlene Kiyoko Shigekawa is the daughter of Kiyoshi Shigekawa. She was born in Poston and raised in Anaheim, CA.

Although Marlene spent the first 10 months of her life in Poston, she was not fully aware of her family history until her older brother Gerald—who was also born in Poston—had learned about the camps in history class and began to ask questions. “My brother came home from high school and he barged in,” she says. “He said, ‘Mom, were you in prison?’ and she said yes. I went, ‘My mother was in prison? […] What are you talking about?’”

Although her family was active in their local community including their church and the YMCA, Marlene says she grew up fairly isolated from the Japanese American community. “Anaheim was very rural—a lot of orange groves,” she says. “Going to a Japanese school would have been too far to drive, and we were so active already in these things. I think my mom just wanted us to be all American.”

When Marlene was 12 years old, she began to feel the stigma associated with her Japanese heritage. “One time, [my family and I] were sitting at the kitchen table, and we saw our Caucasian neighbors coming over. We were eating with chopsticks and chawan and stuff, so [my mother] ran and she took everything and put them in the kitchen sink so they wouldn’t know we were eating Japanese food,” she says. “The message I got was: you’ve got to hide your Japanese side.”

After a career in tech and project management, Marlene began to reconnect with her heritage while working as a diversity consultant in the corporate world. She currently serves as the Executive Director of the Poston Community Alliance, a nonprofit organization dedicated to preserving the history of Japanese Americans who were incarcerated at Poston. She is also a filmmaker who directs and produces films about survivors and descendants of Japanese American incarceration during World War II.