“She always said, ‘I was studying U.S. history, and I learned that I had all these rights as an American citizen.’ I think it was hard for her to reconcile what she studied in the textbook and what was happening to her in real life.”

— Sue Sato, on her mother

Jane Akimoto

Nisei

Jane Akimoto was born in Idaho Falls, ID, and raised in Los Angeles. She was 16 years old when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. “My mom was at a friend’s house, and they were dancing when Pearl Harbor happened,” recalls her daughter Susan. “As soon as they stopped making the announcement, they turned the radio off and all went home. They knew that it meant something bad was going to happen.”

After Executive Order 9066 was issued a few months later, Jane’s family was sent to the Santa Anita Assembly Center, where they were required to sleep in horse stalls on “mattresses” made from canvas bags stuffed with hay. They bathed in overcrowded communal showers with a ratio of 1 shower for every 30 incarcerees. “As a teenage girl, I think it was very traumatizing,” says Susan. “There was no privacy.” After a few months, Jane and her family were transferred to Amache.

Before the war, Jane’s family was close-knit, often sharing stories around the dinner table. But in the communal mess halls, the family grew distant. “People just wanted to eat with their friends,” says Susan. “The family ate together infrequently. It really broke up the family unit.” As the war continued, three of Jane’s brothers enlisted in the 100th Infantry Battalion and the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. Only one brother returned. Family dinners were never the same again.

Jane often reminisced about studying U.S. history in high school before the war. “She always said, ‘I was studying U.S. history, and I had all these rights as an American citizen,’” Susan recalls. “I think it was hard for her to reconcile what she studied in the textbook and what was happening to her in real life.”

The following year, Jane and her family joined a seasonal leave program and worked on a sugar beet farm in Idaho. “It was the worst work in the world,” says Susan. “Worse than being in camp because it was cold, back-breaking work.” After the harvest season ended, Jane’s parents struggled to find work elsewhere and chose to return to Amache. Jane, on the other hand, relocated to Salt Lake City, where she worked as a housekeeper and completed high school. While attending nursing school, Jane met her husband. The couple later moved to California and raised a family. Although she did not speak openly about her incarceration to her children, Jane began to share more about her wartime experiences with her grandchildren before she passed away in 2012.

Jane’s family information as it appears in the Final Accountability Roster for Amache. Courtesy of Densho Encyclopedia.

Listen to this portrait.

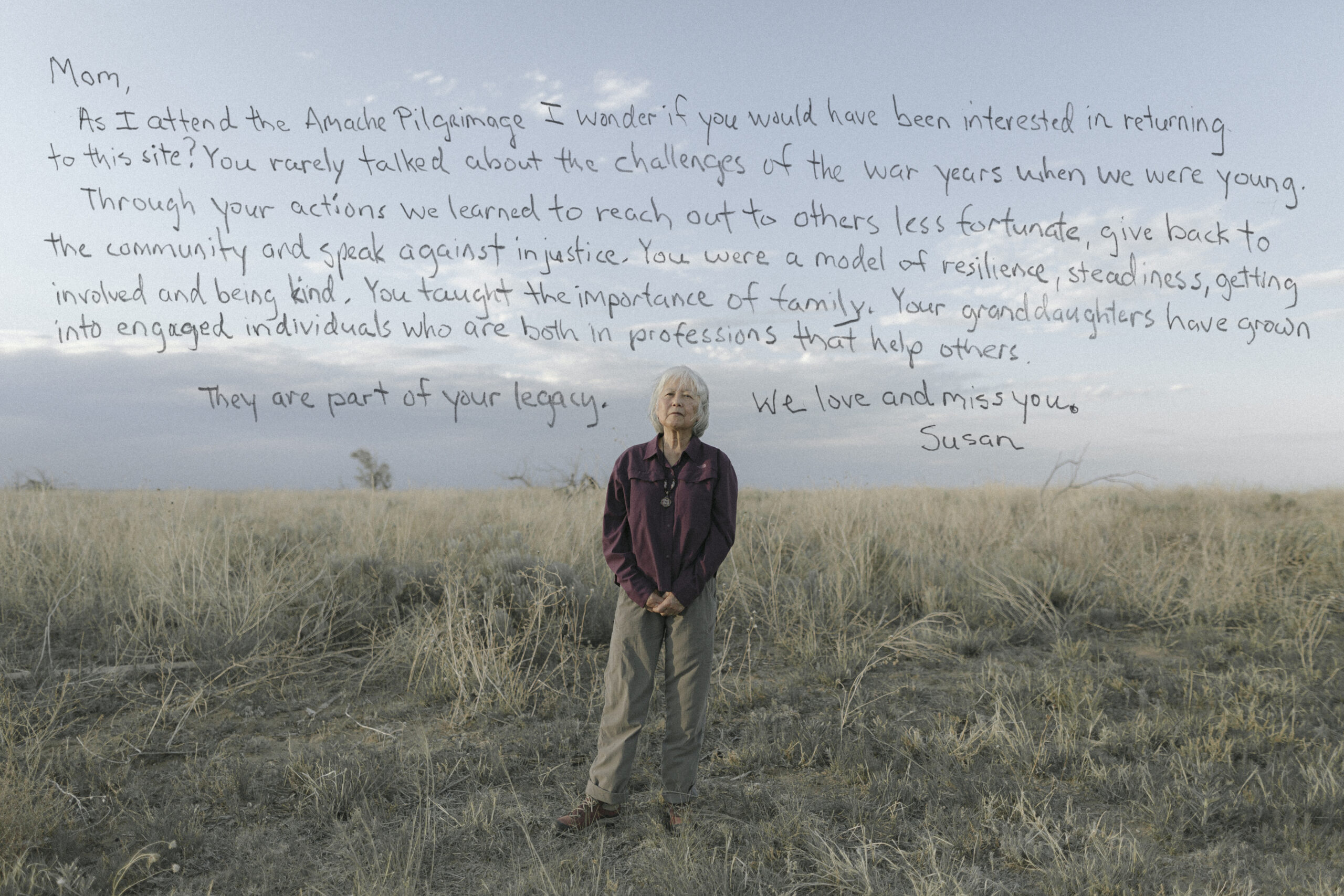

Susan Reiko Sato

Sansei

Susan is the daughter of Jane Akimoto. She was born in Salt Lake City, UT and raised in Upland, CA.

Growing up, Susan recalls that her mother rarely spoke about her incarceration. “Japanese culture teaches us not to complain—not to speak out and cause problems. That really carried through in the Nisei generation,” she says. “I think my mom just buried a lot of her feelings about camp.”

Susan’s awareness of her family’s history deepened in college, around the time when the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 was passed and her mother received her reparations check. “At the time, it was a lot of money,” Susan remembers. “It was $20,000 that we didn’t have.” Susan recalls her mother giving away her check to struggling family members and to her own children, one of whom used it towards a downpayment on a new house. “My mom was very generous. She really tried to help out people,” Susan says. “I think what meant a lot to her was that there was an official apology.”

“Japanese culture teaches us not to complain—not to speak out and cause problems. That really carried through in the Nisei generation. I think my mom just buried a lot of her feelings about camp.”

— Susan Sato

Listen to this portrait.

Mariko Aili Ferronato

Yonsei

Mariko Ferronato is the grand-daughter of Jane Akimoto. She was born in Pasadena, CA and raised in Sacramento, CA.

Growing up, Mariko attended predominantly white schools from kindergarten through middle school and became more aware of her racial identity upon entering a more diverse high school. “That’s where I connected more with a lot of Asians and African Americans,” she says. Still, as a multiracial Japanese American, Mariko often felt caught between identities. “I was dating a white guy, and his friend called me a ‘cheating Jap’ because I was hanging out with all the Asians,” she shares. “That relationship ended on the same day. And I went on this whole self-identity discovery about what it means to be a Hapa.”

Mariko says she learned about the camps primarily from her mother, Sue. When Jane did speak about her incarceration, she was often selective about what she shared. “She kept it very positive, like ‘I got to hang out with my friends a lot, and we would have dances,’” Mariko recalls. “I was a pretty selfish teenager. Looking back, I think about how much of that was her trying to relate to me—the teenager who wanted to be with her friends all the time.”

“She kept it very positive, like ‘I got to hang out with my friends a lot, and we would have dances.’ I was a pretty selfish teenager. Looking back, I think about how much of that was her trying to relate to me—the teenager who wanted to be with her friends all the time.”

— Mariko Ferronato

Listen to this portrait.

Hana Michiko Ferronato

Yonsei

Hana Michiko Ferronato is the grand-daughter of Jane Akimoto. She was born and raised in Sacramento, CA.

Growing up, Hana says she was aware of her family history from a young age. But what stood out to her was how Jane’s lived experience conflicted with what she was learning in school about American ideals during the war. “She was a pretty idealistic young person, and then to have all of this happen—it was against everything she had ever been taught or had believed in terms of being American, being a young person in a democracy,” Hana explains. “Everything that she had been taught to believe was taken away.”

As a multiracial Japanese American, Hana grew up with strong ties to her Japanese heritage. “When I was really little, I wished I was 100% Japanese,” she reflects. “I suppose I struggled with being multiracial.” Her identity and family history have made her more conscious of the legacies of social injustice in American history. “As someone who’s multiracial, I have both legacies in me— even though my family was unjustly incarcerated because of racism and xenophobia, Japan also has this very colonial and violent history,” she says. “We inherit both things. It’s something we have to lean into—to have compassion for our ancestors while reflecting on what we can do now.”