Located in southwestern Arizona, Colorado River Relocation Center—known as Poston—was a War Relocation Authority concentration camp located on the ancestral land of the Pipa Aha Macav, Nüwü, Hopituh Shi-nu-mu and Diné of the Colorado River Indian Tribes. It was named after Charles D. Poston, the first Superintendent for Indian Affairs in Arizona.

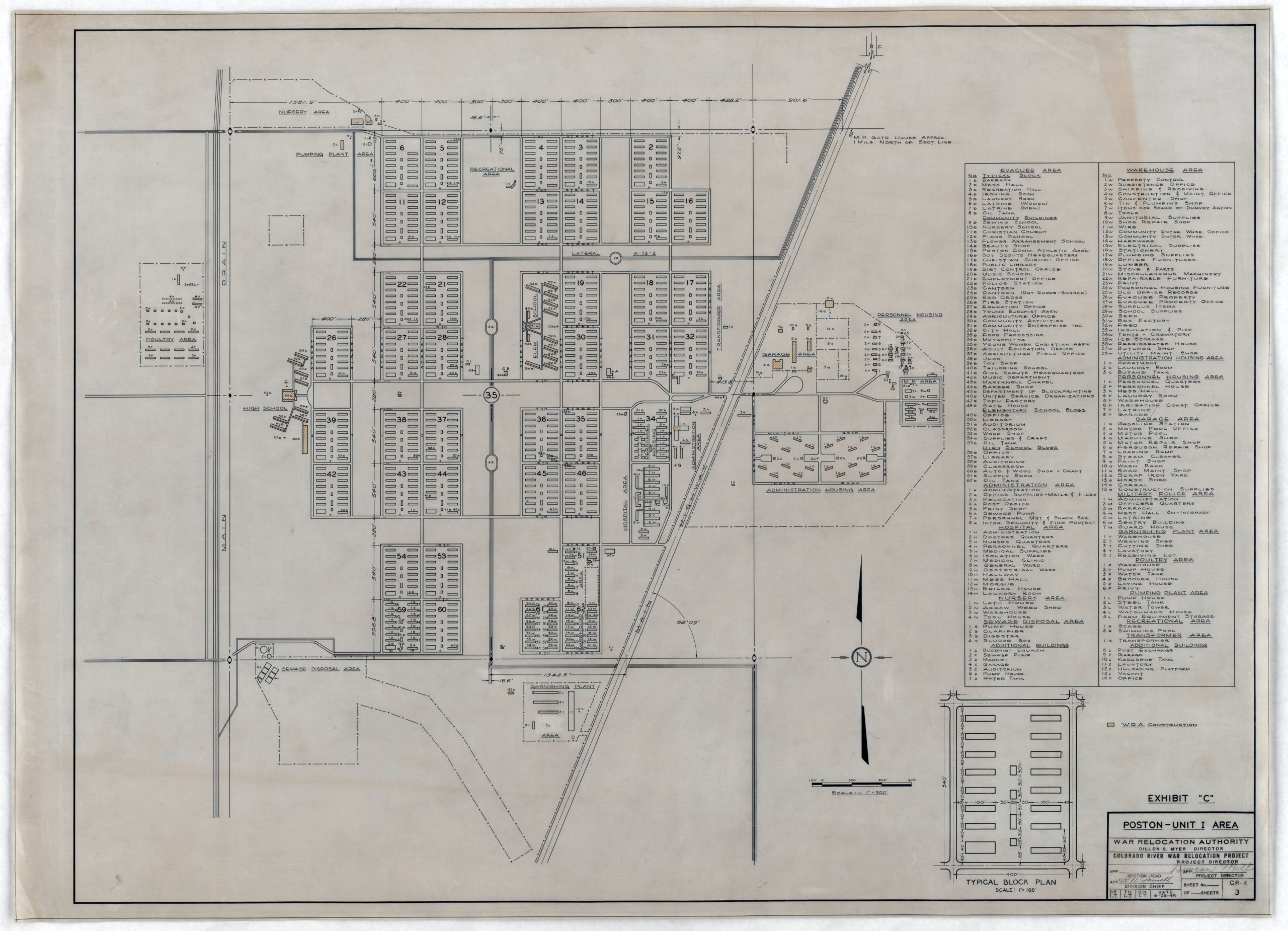

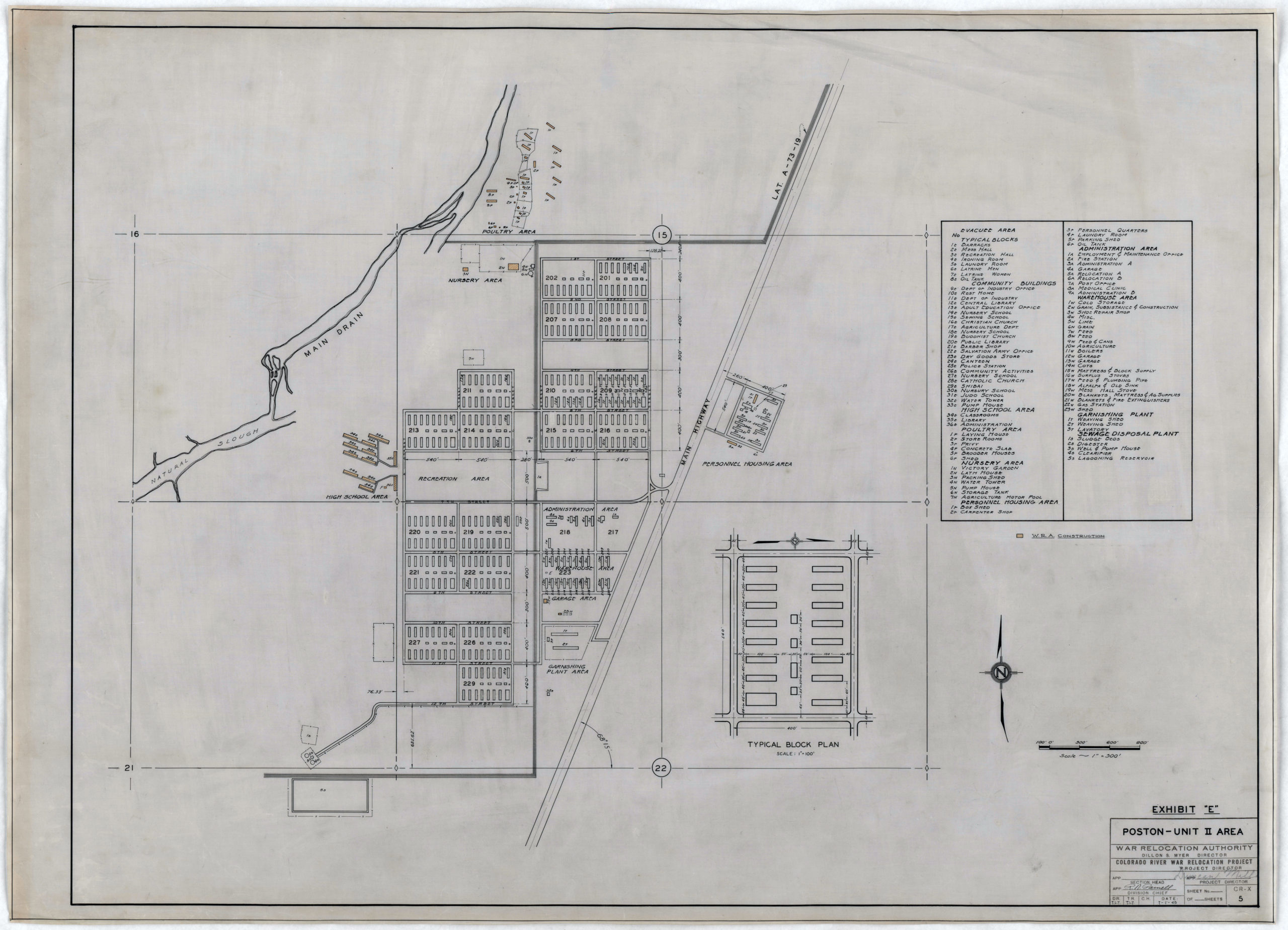

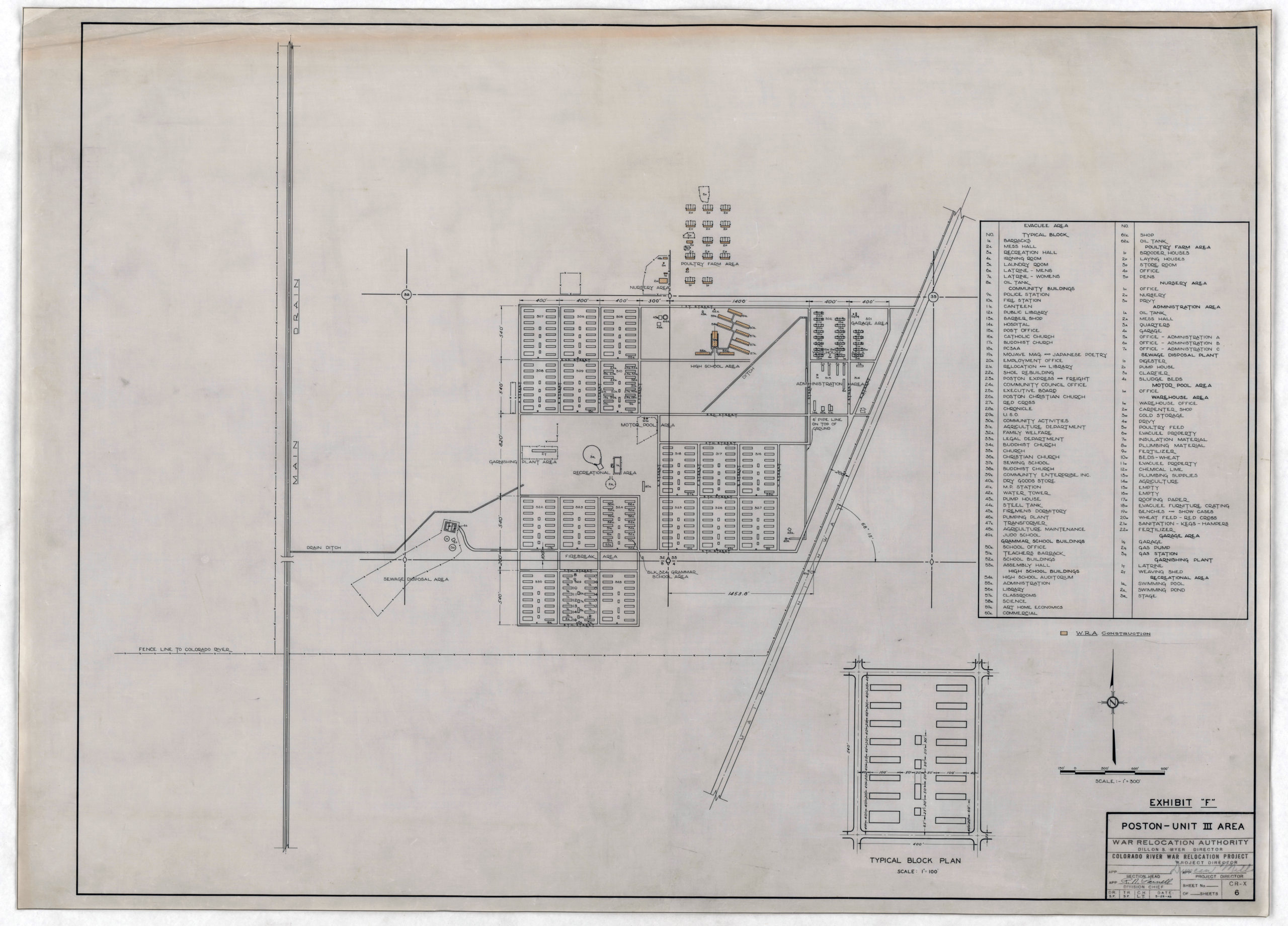

The War Relocation Authority‘s master plot plan for Poston I, II and III. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

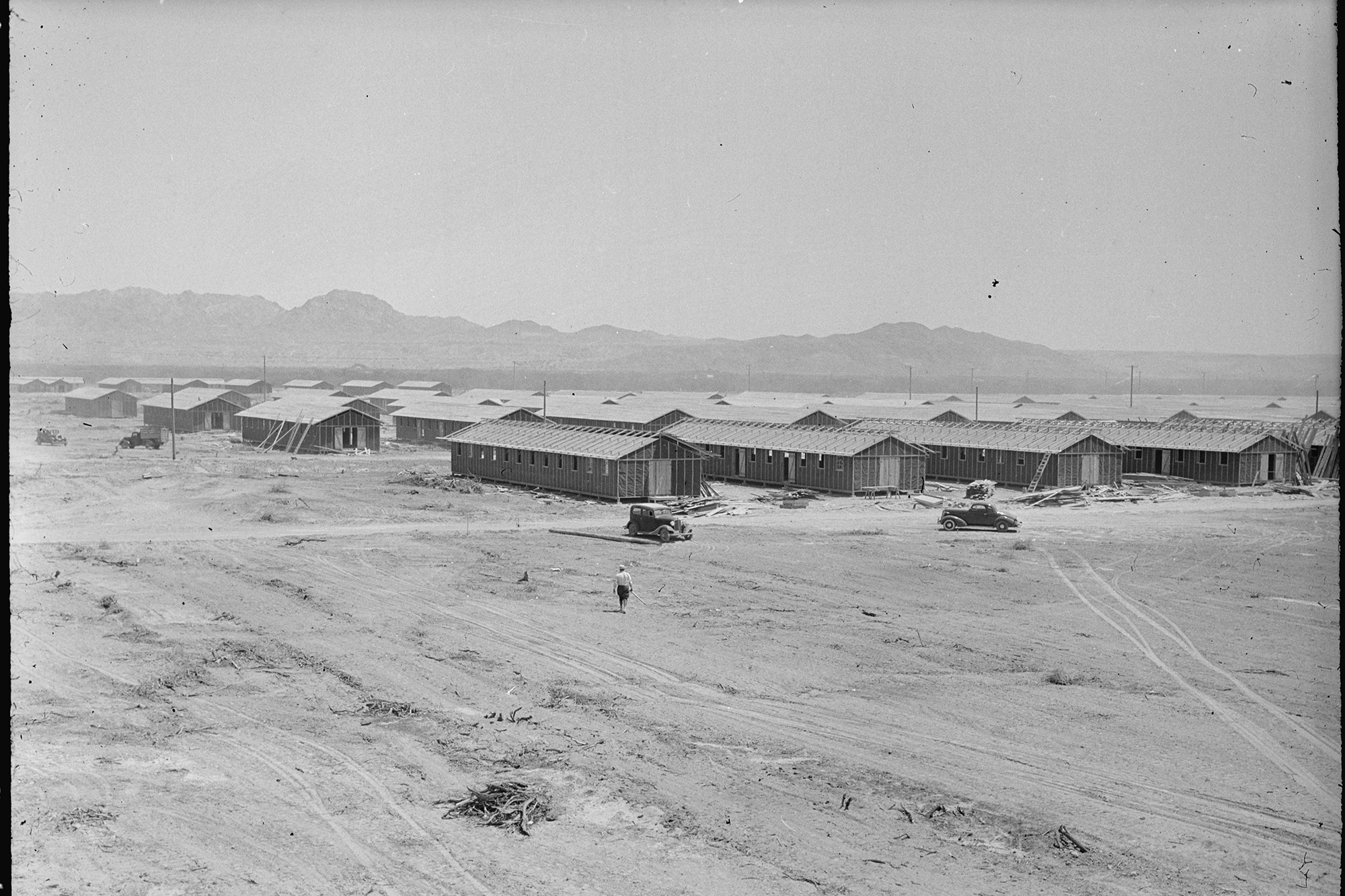

Poston was situated on 71,000 acres in the Sonoran Desert, where summer temperatures soared above 100 degrees and winter temperatures dipped below zero at night. When the first incarcerees began to arrive in the summer of 1942, many suffered heat stroke and were given ice, wet towels, and salt pills to prevent dehydration. In addition to the harsh weather conditions, the camp infrastructure was incomplete. The hospital and mess halls were unfinished. There was no refrigeration for meat. The plumbing and water supply systems were faulty.

Camp I of the Poston concentration camp. April 24, 1942. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

The Poston concentration camp is located on the Colorado River Indian Tribes Reservation. October 23, 2023.

Before the establishment of the Tule Lake Segregation Center, Poston was the largest War Relocation Authority camp, with nearly 18,000 incarcerees. It was divided into three separate camps—Poston I, II, and III—which incarcerees dubbed “Roasten,” “Toasten,” and “Dustin.” Poston was considered the third largest “city” in Arizona at the time.

Incarcerees mostly subsisted on their own labor, growing their own crops, raising livestock, and clearing and irrigating the land. They built schools, auditoriums, and other facilities with handmade adobe bricks and contributed to the war effort by making camouflage nets.

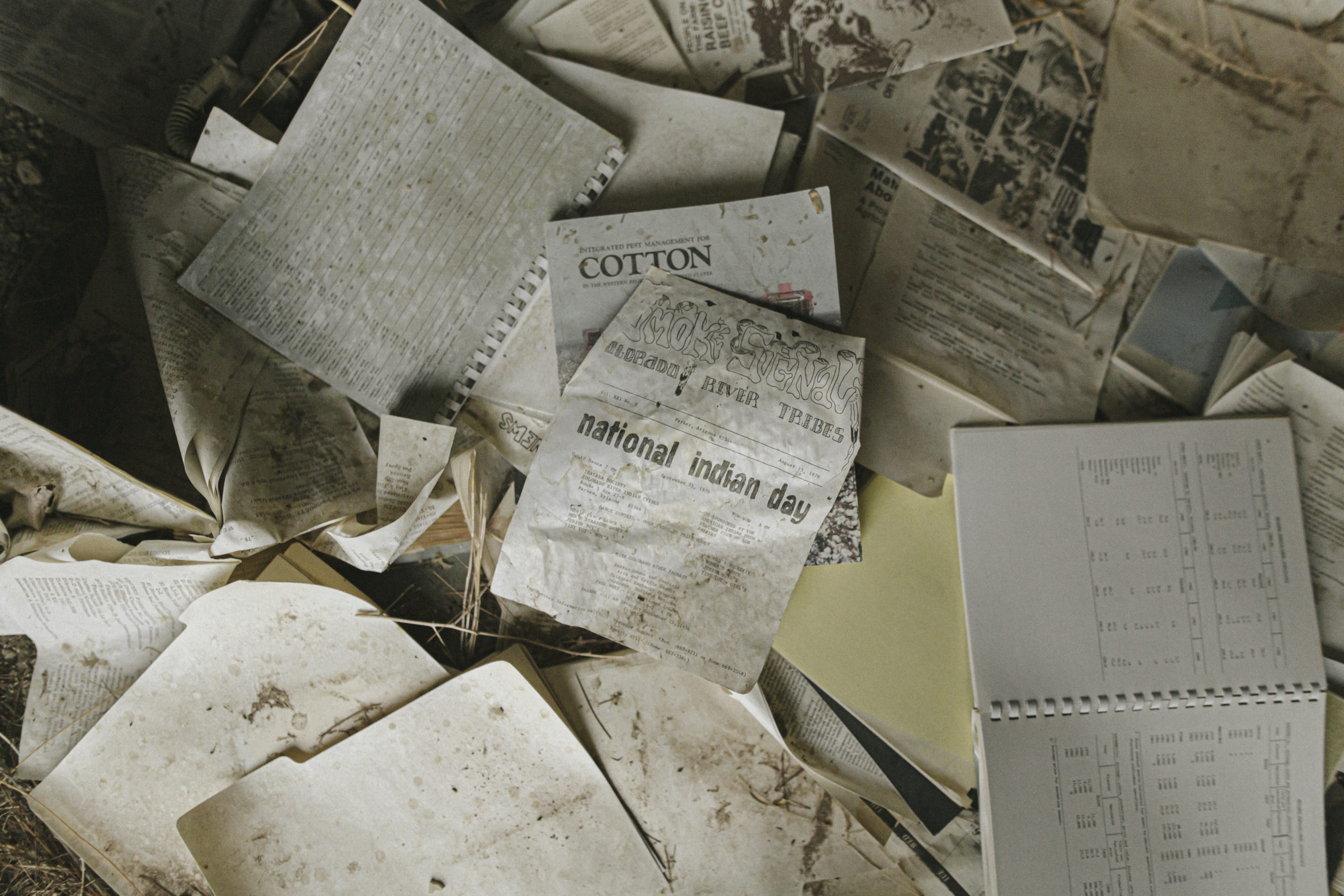

Many of the original structures at Poston I, II and III have been demolished or fallen into disrepair. Poston I—pictured here—is the largest of the three units and once housed an elementary school, auditorium and gymnasium.

Incarceree students gathered in classrooms at Poston Elementary School—designed and built by incarcerees—to continue their education during their incarceration.

Still, incarcerees at Poston did not always accept their conditions passively. In August of 1942, adobe workers organized a labor strike. When the administration announced that only American-born Nisei could serve on the elected “Temporary Community Councils,” incarcerees formed an “Issei Advisory Board” in protest. A week-long strike occurred in November 1942 when two incarcerees were held without due process for allegedly injuring individuals accused of being administration informers. Poston also had the largest number of draft resisters, although they were not as organized as those at Heart Mountain.

Aside from “home front” labor like making camouflage nets for the US military, incarcerees constructed buildings, roads and a robust irrigation system that continues to feed into the surrounding farmlands today.

Although they are slowly being restored by grassroots organizations, structures at the Poston concentration camp are vulnerable to decay and arson.

While incarcerees could obtain day passes to visit the nearby town of Parker, War Relocation Authority officials and local residents discouraged them from visiting. Local businesses often refused service to Japanese Americans, and a local barbershop had a sign reading, “Japs, keep out, you rats.” A wounded Nisei veteran on crutches was evicted from a local business, and three Nisei soldiers were stoned by a gang led by a drunken deputy sheriff while on furlough before going overseas.

The Colorado River Indian Tribes opposed the idea of housing a camp on their reservation, but the Office of Indian Affairs and U.S. Army proceeded with the plan in hopes of utilizing incarceree labor to develop the area. Upon the camp’s closing, many of the camp buildings were transferred to the Colorado River Indian Tribes and have since been repurposed for use by their community.

Despite these challenges, incarcerees at Poston found ways to cope. They dug subterranean spaces under their barracks to escape the heat, beautified their camp with hardy trees like cottonwood to provide shade, and built their own furniture from scrap lumber to adorn their barracks. They also constructed theatrical stages to host Japanese “shibai” performances and movie screenings, which helped boost morale among the incarcerees. Poston is also known as the birthplace of the hand-carved wooden bird pins, a famous artifact made by Japanese American incarcerees.

Why is Poston significant?

Poston was built on the Colorado River Indian Reservation. The Office of Indian Affairs saw the construction of a concentration camp as a chance to obtain roads, irrigation, and other necessities for economic development without funding them. The Tribal Council opposed the decision because they did not want to participate in an injustice, but the decision was approved after they were overruled by the Office of Indian Affairs and the U.S. Army.

When the camp closed on November 28, 1945, the buildings, roads and other improvements made during the camp’s operations were transferred to the Colorado River Indian Tribes. However, the rental fee that the War Relocation Authority had agreed to pay to the Colorado River Indian Tribes largely disappeared in deductions for land improvements, and the tribes did not receive the financial compensation that they were promised.

Despite this history, the Colorado River Indian Tribes have worked with the Japanese American community to preserve the site and facilitate in-person pilgrimages for survivors and descendants of the Poston concentration camp.