“They didn’t have to explain anything to you. No due process. The grounds were: you were Japanese. We never lived together as a family again.”

— Nikki Nojima Louis

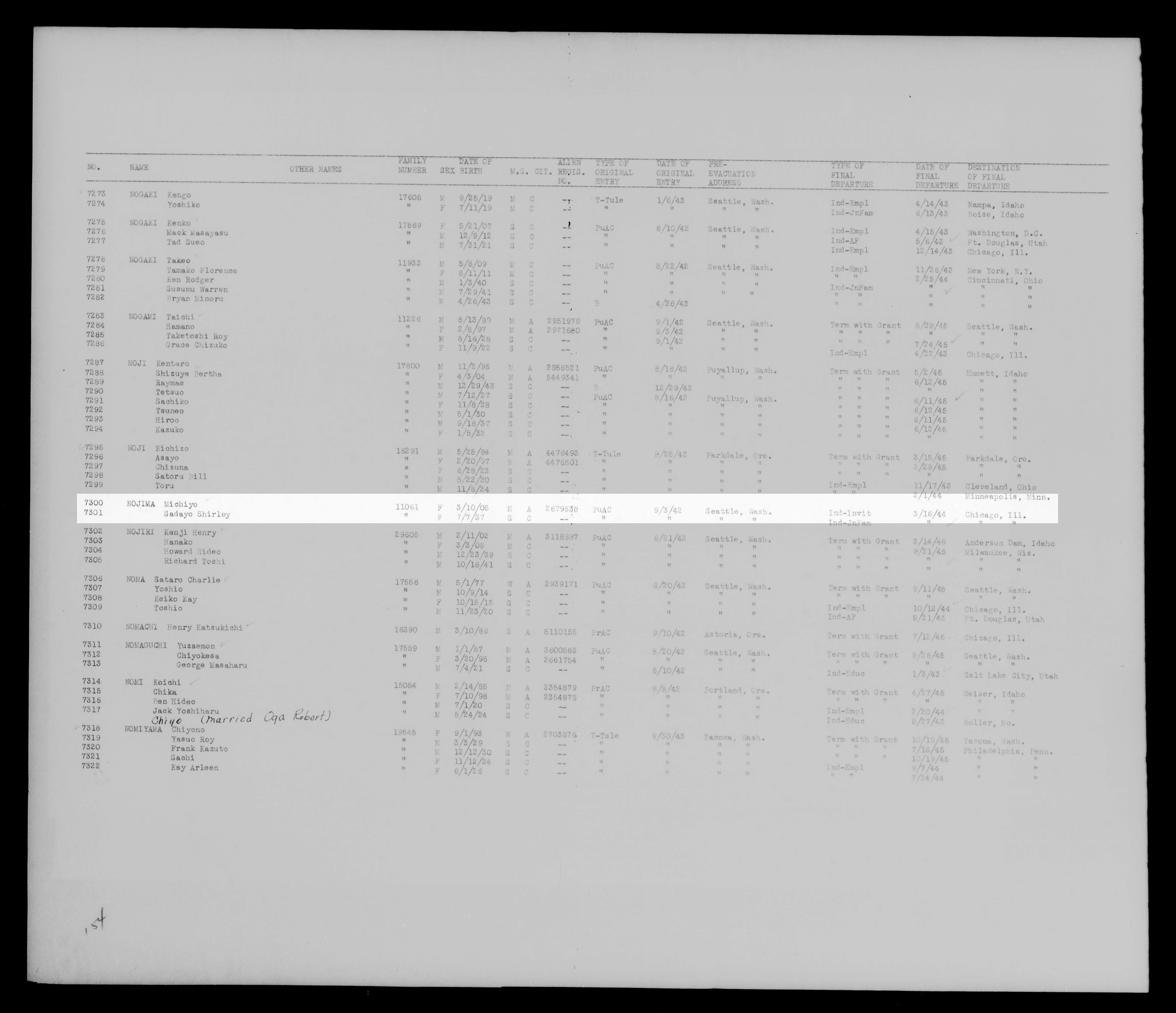

Nikki’s information as it appears in the Final Accountability Roster for Minidoka. Courtesy of Densho Encyclopedia.

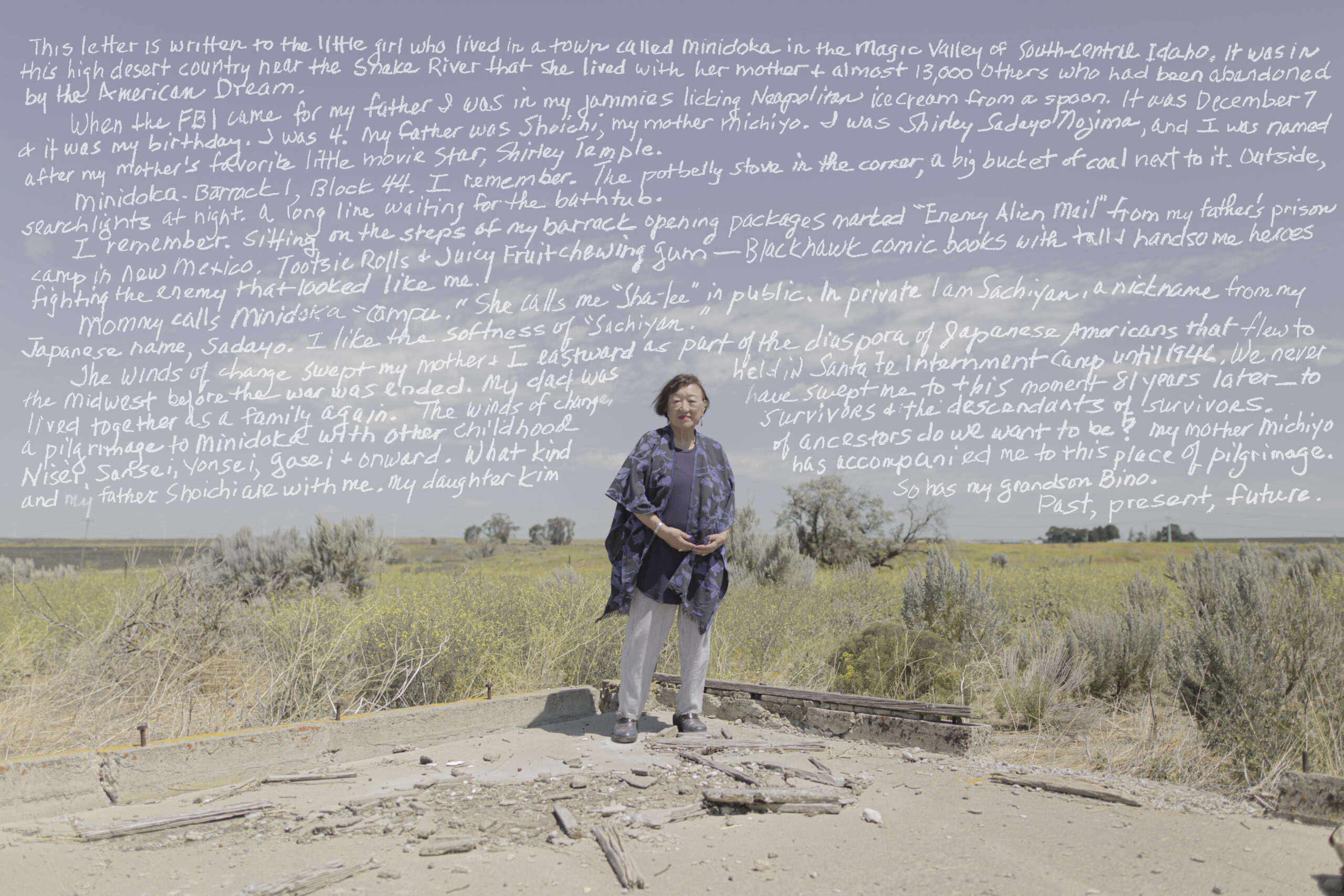

Listen to this portrait.

Nikki Nojima Louis

Nisei

Nikki Nojima Louis was born in Seattle, WA. She was celebrating her fourth birthday when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. That evening, the FBI entered her home and arrested her father. “They didn’t have to explain anything to you. No due process. The grounds were: you were Japanese,” she says. “We never lived together as a family again.” Her father was detained in Lordsburg Internment Camp and Santa Fe Internment Camp.

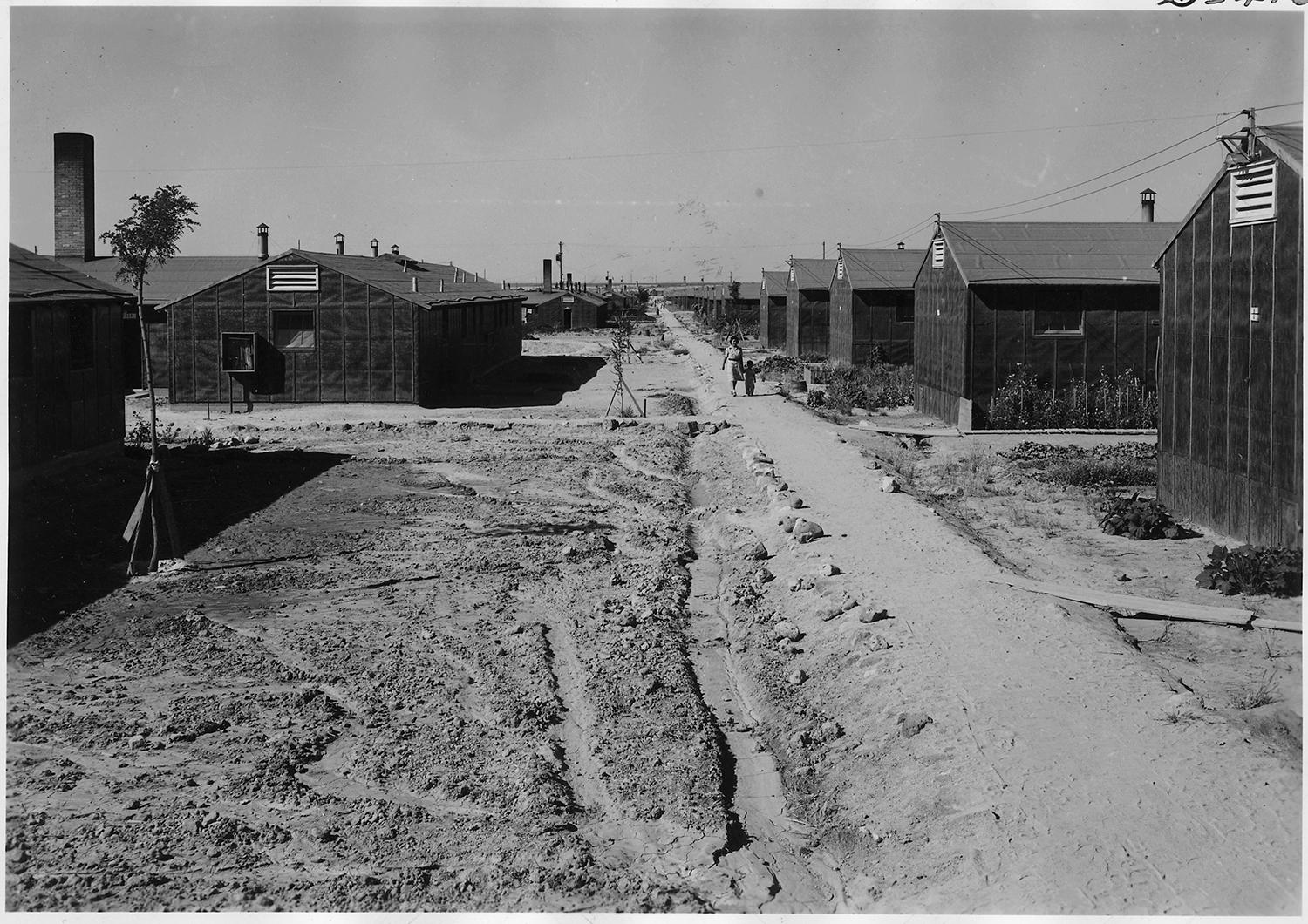

Soon after, Nikki and her mother were sent to Puyallup Assembly Center. Upon their arrival, they were given large cloth bags. “We were pointed to a stack of hay and told to fill the bags with hay for mattresses,” she says. “Our new home was called ‘Camp Harmony.’” Nikki and her mother were held there for five months before they were transferred to Minidoka.

Nikki and her mother lived on Block 44 in Minidoka. She says a typical housing unit was a 20’ by 100’ barrack equipped with a lightbulb and a coal-burning pot belly stove. “One cot, one mattress, two blankets per person,” she says. “We were always standing in line. Standing in line to eat in the mess hall. Standing in line to do laundry. Standing in line to order supplies or get to the latrines.”

Shortly before the end of the war, Nikki and her mother left camp on early release and headed to Chicago. Upon his release from Santa Fe Internment Camp in 1946, Nikki’s father joined them briefly, but he decided to return to Seattle to be closer to his community. Nikki’s mother decided to stay behind in Chicago. “My mother no longer wanted to live around Japanese Americans,” Nikki says.

Nikki and her mother lived in modest housing on the north side of Chicago while her mother worked as a maid at a local hotel. With savings from a sewing school she ran before the war, Nikki’s mother enrolled Nikki in an all-white private school. “I went to this private white school with bedbug bites,” she says. “They didn’t know what these bites were on my arms.”

When Nikki asked her mother if she could change her name from Shirley Sadayo to Nikki in the third grade, she welcomed the idea. “My mother accepted everything. If that’s what Americans did, she embraced it.”

At age 16, Nikki heard that her father had had a heart attack and decided to move to Seattle to be with him. She recalls visiting a cafe in Nihonmachi with him and chatting with the owner who recognized her as a baby. Shortly after Nikki’s 19th birthday, her father had another heart attack and passed away. “I spent the first three years of my life with my father, and the last three years of his life with him,” she says. “I treasured those last three years because that’s when I got to know my dad.”

Nikki currently lives in Albuquerque, NM. “As a child sitting on the steps of my barrack in Minidoka, I used to open packages marked ‘Enemy Alien Mail’ from my father’s camp in Santa Fe,” she says. “New Mexico was a magical place, and it still is for me because of the magic of the stories I continue to discover.” Nikki is a writer, performer and producer who tours a new reader’s theater play on the Japanese American incarceration every year.