Kamei Family

Heart Mountain

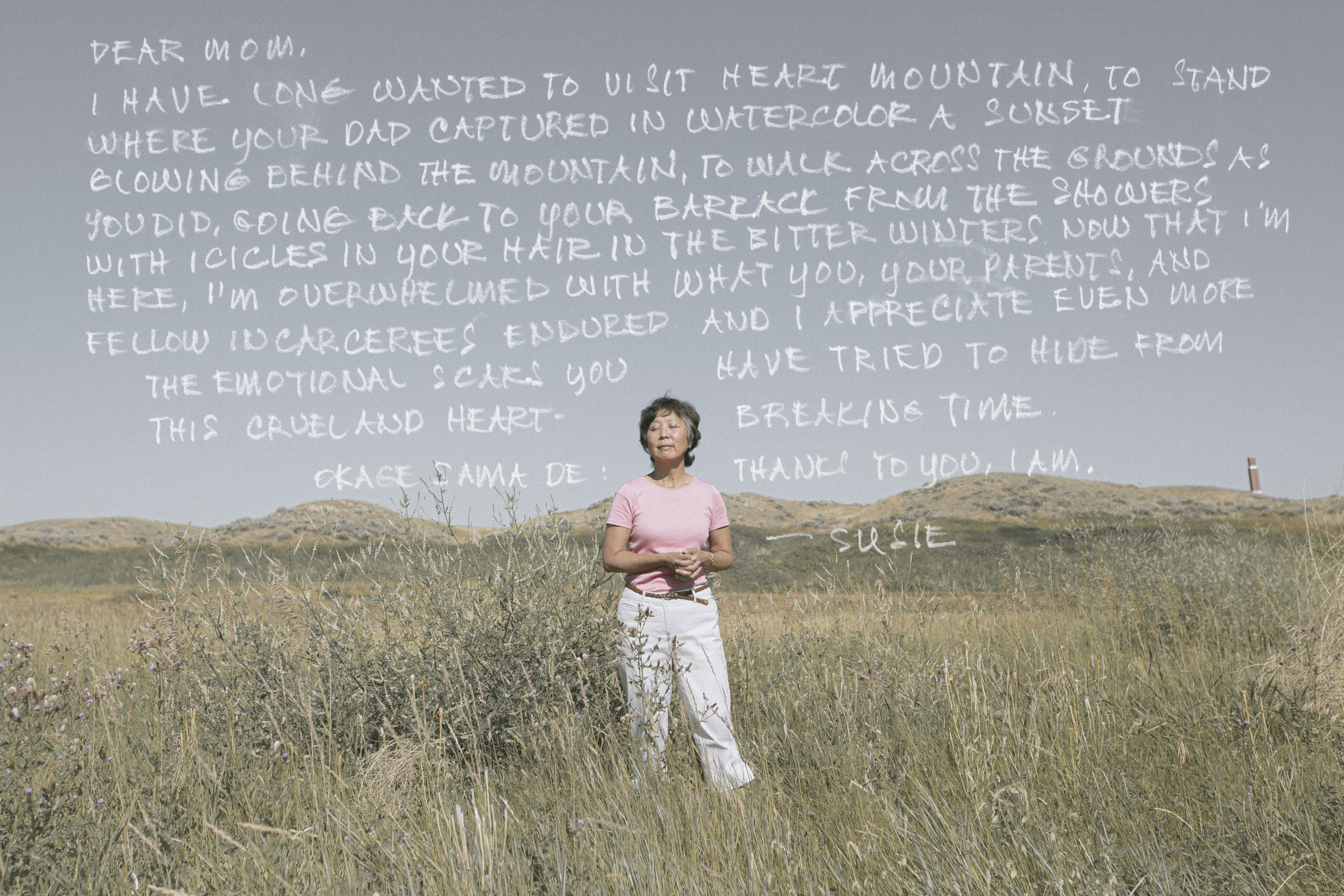

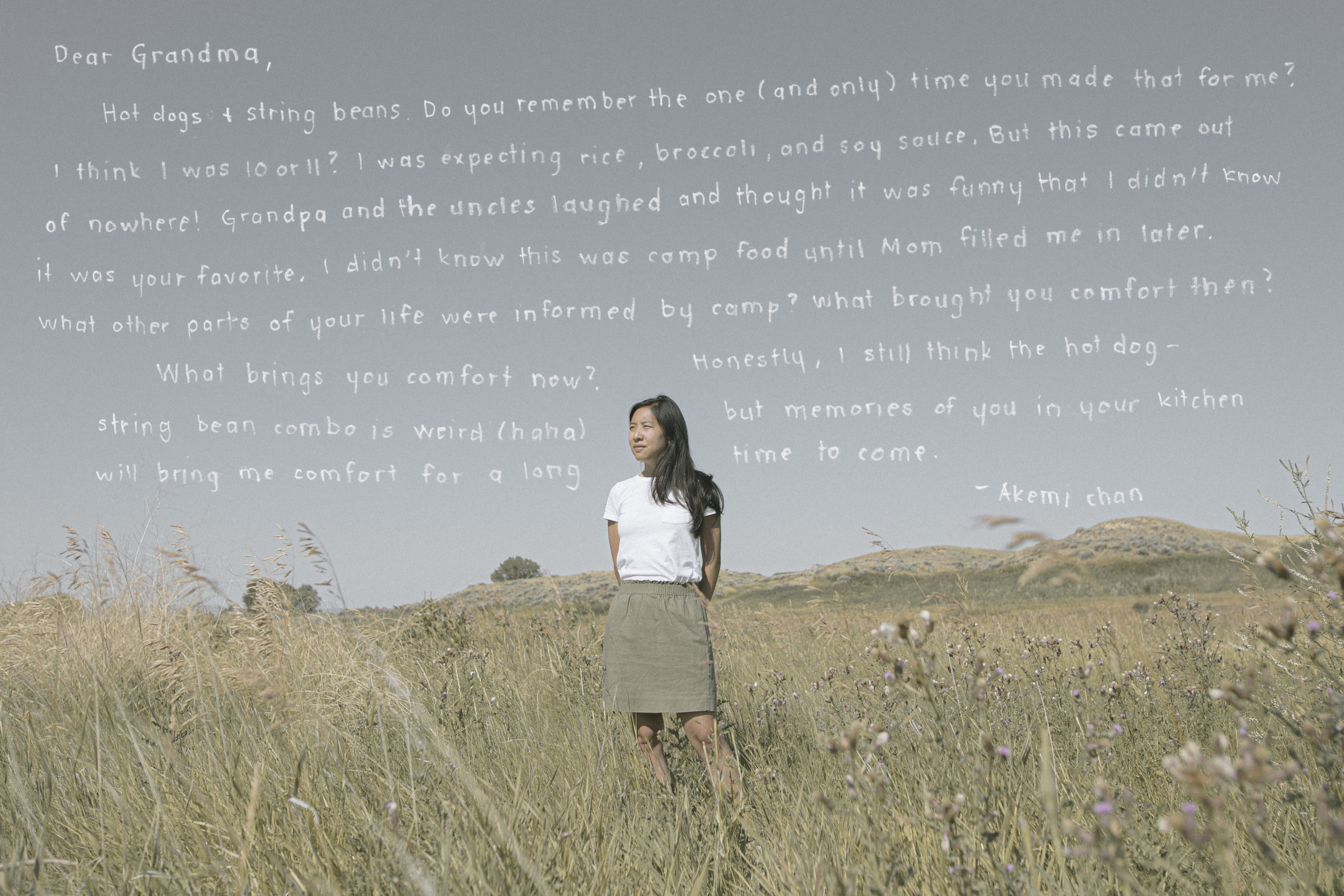

Susan H. Kamei and her daughter Akemi Leung remember their ancestor Tamiye Kurose, who was incarcerated at Heart Mountain.

Susan H. Kamei and her daughter Akemi Leung remember their ancestor Tamiye Kurose, who was incarcerated at Heart Mountain.

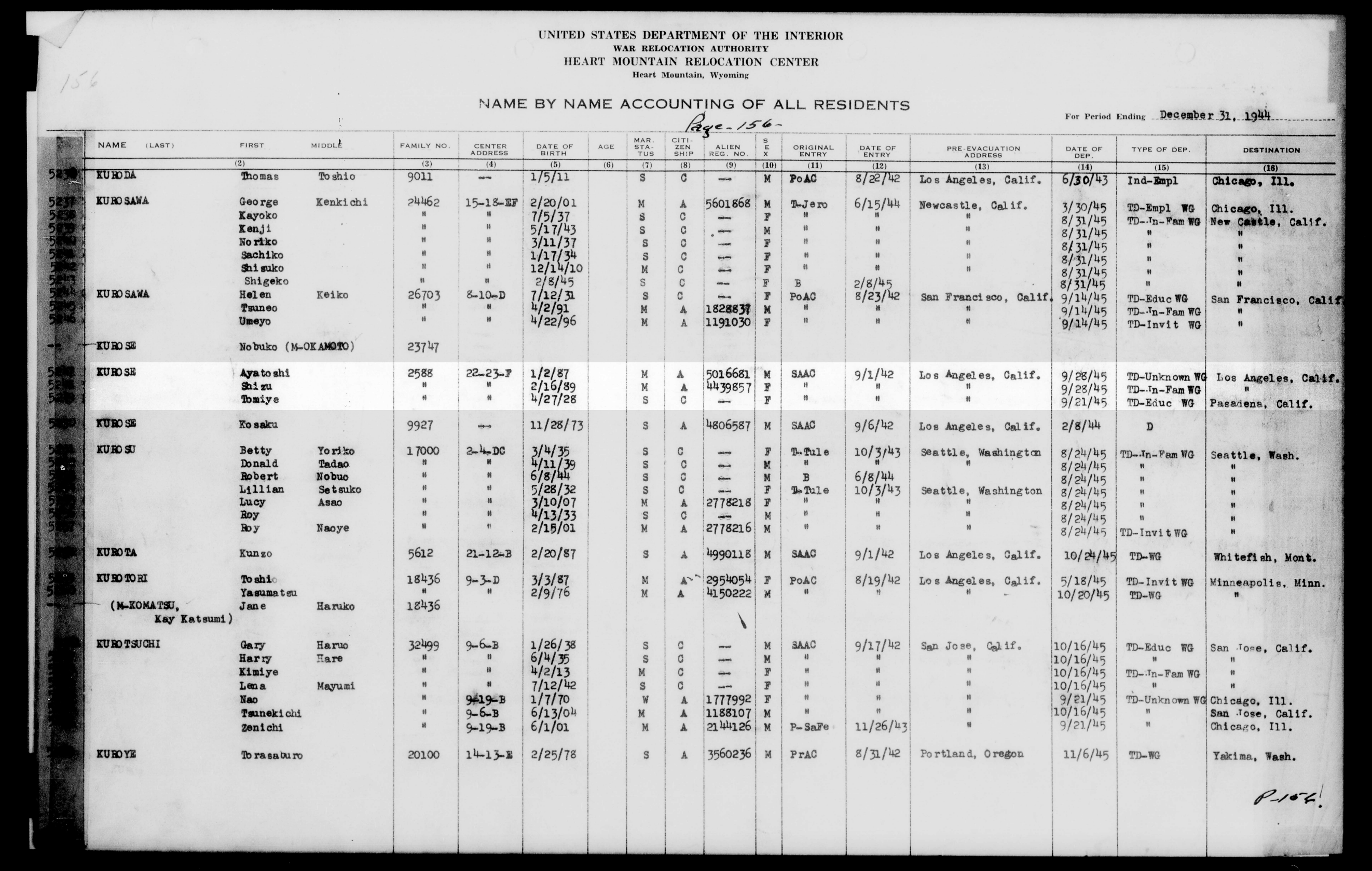

Tami Kurose was born in Los Angeles between Issei parents. Her mother was classically trained in traditional Japanese dance, koto, shamisen and ikebana, and her father played the shakuhachi. They married in Little Tokyo and had two daughters: Tami and her older sister, who passed away due to tuberculosis when Tami was four years old.

Tami was a high school freshman when Executive Order 9066 was issued. She and her parents were imprisoned at Santa Anita Assembly Center before they were transferred to Heart Mountain. Tami graduated from high school in camp, and after her release, she stayed at the Pasadena Hostel, one of the first hostels established on the West Coast to provide temporary housing for Japanese Americans returning from the camps. Tami worked as a live-in nanny in Pasadena while her parents worked in neighboring Altadena as gardeners and housekeepers. “It was quite a while before they actually returned to Little Tokyo,” says Tami’s daughter Susan.

Although Tami rarely spoke about her incarceration with her children, she once recalled being harassed during her first semester in college after the war. “The one story that she told me from that time was how she had tomatoes and rocks thrown at her,” says Susan. “It was just a moment out of probably many, many incidents.”

Aside from a short detour during a road trip to Yellowstone many years ago, Tami never returned to Heart Mountain before she passed away in 2023.

Susan H. Kamei is the daughter of Tami Kurose. She was born in Los Angeles and raised in Anaheim.

In junior high, Susan was called a racial slur at school. “I went home angry and upset, anticipating that when I told my mother, she would be sympathetic,” she says. “What surprised me to this day is that she actually got angry and said, ‘You don’t know what it’s like to face racial discrimination.’ […] That I should be so grateful that all they did was call me names because she had experienced so much worse.”

This was one of the few times Susan had heard her mother mention her incarceration. “It might have been the only occasion that she tapped into that suppressed anger. I never heard anything like it from her ever again,” Susan says. “What I now know about Issei and Nisei is that they didn’t tell us these things because they wanted to protect us. Kodomo no tame ni. We keep these things to ourselves because we don’t want to burden our children with our burdens.”

Susan went on to study law, partly inspired by a conversation with her father—who was incarcerated at Poston—about the property loss his family had experienced after returning from the camps. During her studies, Susan became a member of the legislative strategy team for the Japanese American Citizens League and contributed to the successful passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988.

Susan is currently the managing director of the Spatial Sciences Institute and an adjunct professor of history at the University of Southern California, teaching an undergraduate course about the wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans. She is the author of “When Can We Go Back To America?: Voices of Japanese American Incarceration during WWII”, a narrative history of Japanese Americans who were incarcerated during World War II.

Akemi Leung is the maternal grand-daughter of Tami Kurose. She was born in Pasadena between a Japanese American mother and a Chinese American father.

Growing up, Akemi enjoyed spending time with her grandmother. “I absolutely loved going to her house because she would give me all of the American kid things that I didn’t get otherwise,” she says. “She would plop me in front of their TV, which had cable […] and she would buy me Kid Cuisine.” In contrast, her mother used to pack her soba lunches, which led to prying questions from fellow classmates. “I’ve wondered: did [my grandma] over-index on the ‘all-American’ kind of thing?,” she says.

Akemi says her grandmother did not place much emphasis on passing down their Japanese heritage. “I never got the sense that she really wanted us to preserve tradition,” she says. “I remember her watching Japanese soap operas. I remember her speaking Japanese to my grandpa. But never teaching us Japanese—that was definitely not a priority.”

Much like her mother, Akemi has rarely heard her grandmother speak about her incarceration or any aspirations she had growing up. “She’s kind of a vault,” she says. “I think there’s shame in being incarcerated, whether it was wrongfully done or not. Prison is intended to be a humiliating experience. There’s no privacy. You’re supposed to be bored and driven up the walls. You’re not protected from each other, or from the guards.”