“People would not even knock—they would just walk into the house to look for stuff they can ‘purchase’ or take.”

— Mitch Homma

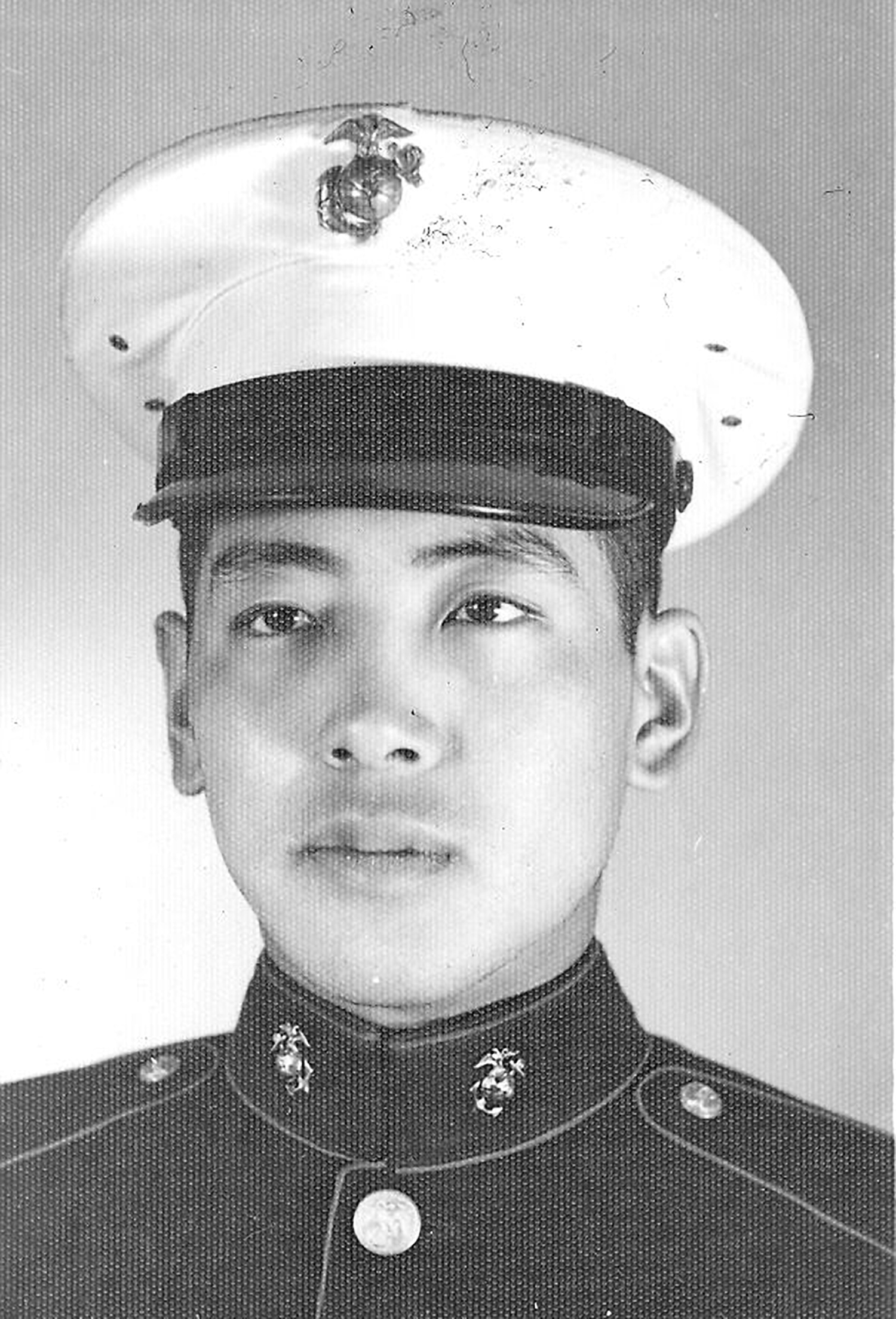

Hisao Homma

Nisei

Hisao Homma was born and raised in Los Angeles. Shortly after the Pearl Harbor attacks, Hisao’s father began hearing rumors about potential home raids. In response, he drained the koi pond in their backyard and burned photographs and documents that could trace the family back to Japan. Within days, the F.B.I. arrived at the Homma residence and confiscated their radios and heirloom Japanese swords. “Dad remembers sitting on the curb when the F.B.I. came to the house,” recalls Hisao’s son, Mitch. “The kids were forced to sit on the curb outside.”

Meanwhile, Hisao’s grandparents, who had come to the U.S. as Baptist missionaries and lived in a church parsonage, were also arrested by the F.B.I. His grandfather, a Baptist minister and substitute Japanese language school teacher, was sent to Tuna Canyon Detention Station and later to various internment camps, including Santa Fe Internment Camp, Crystal City Internment Camp and Lordsburg Internment Camp. His grandmother, also a language school teacher fluent in English, German, and French, was transferred through multiple detention centers in Los Angeles before being sent to Seagoville Internment Camp.

As their “evacuation” loomed, strangers began appearing at Hisao’s family home to collect furniture and belongings. “As a typical Japanese family, they had fairly formal Sunday evening dinners,” Mitch explains. “People would not even knock—they would just walk into the house to look for stuff they could ‘purchase’ or take.” Hisao’s family was forced to part with their valuables for very little, including his grandmother’s grand piano, sold for just $5.

In March of 1942, Hisao and his family were sent to Santa Anita Assembly Center, where they were assigned a horse stall to live in. Hisao’s mother scrubbed their quarters with bleach. “They could never get the smell out of the horse stall,” Mitch says. “Dad always used to comment that whenever we used bleach to clean stuff, it reminded him of Santa Anita.”

Before the war, Hisao’s father had run a dental practice in Sawtelle. Though initially designated for transfer to Manzanar, he requested a move to Amache after learning of their need for medical personnel. In September of 1942, Hisao’s family transferred to Amache, where his father provided dental services to fellow incarcerees.

Over time, however, Hisao’s father’s health declined. “He refused to eat,” Mitch shares. “He basically pined away until he had lost about 35-40 pounds before he had a heart attack and stroke.” In August 1944, Hisao’s father passed away, and eight-year-old Hisao led the procession for his father’s funeral service. “That was the worst walk of his life, walking from the barracks to the cemetery,” Mitch recalls.

Amache incarcerees were responsible for gathering their own coal to heat their barracks in winter, a struggle for Hisao’s widowed mother, who was now raising three children singlehandedly. “They almost froze that winter because they couldn’t gather enough coal to heat the potbelly stove,” Mitch recounts. “They said that was the coldest winter ever.”

The family remained at Amache until its closure in the fall of 1945. They had lost nearly everything: the dental practice, their home, most of their belongings, and the family patriarch. “They couldn’t return to the life they had known in L.A.,” says Mitch. “That life was completely gone.”

Fortunately, Hisao’s grandfather was offered a pastorship through the American Baptist Home Missions Society after the war. “It was a huge act of kindness,” says Mitch. “They stopped [Hisao’s grandparents] from being repatriated and deported during the war, saying these are our missionary workers that we brought to the U.S.” After their release, Hisao, his mother, and siblings joined their grandparents and lived in a church parsonage in Seattle, WA, for over a decade as they worked to rebuild their lives. “Instead of the American government stepping in to help its own people after taking everything from them, it was up to organizations like the American Baptists to help instead,” Mitch reflects.

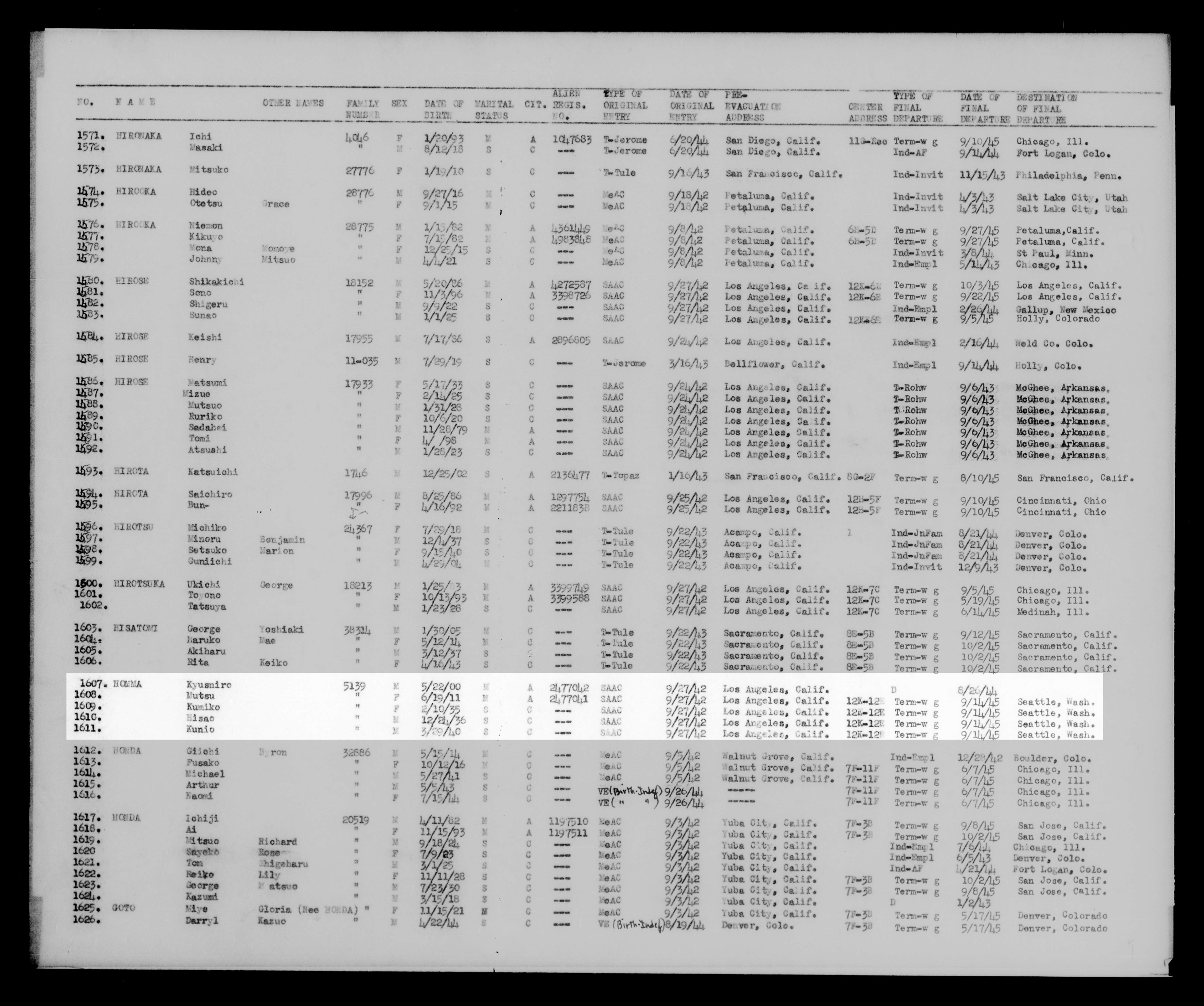

Hisao’s information as it appears in the Final Accountability Roster for Amache. Courtesy of Densho Encyclopedia.

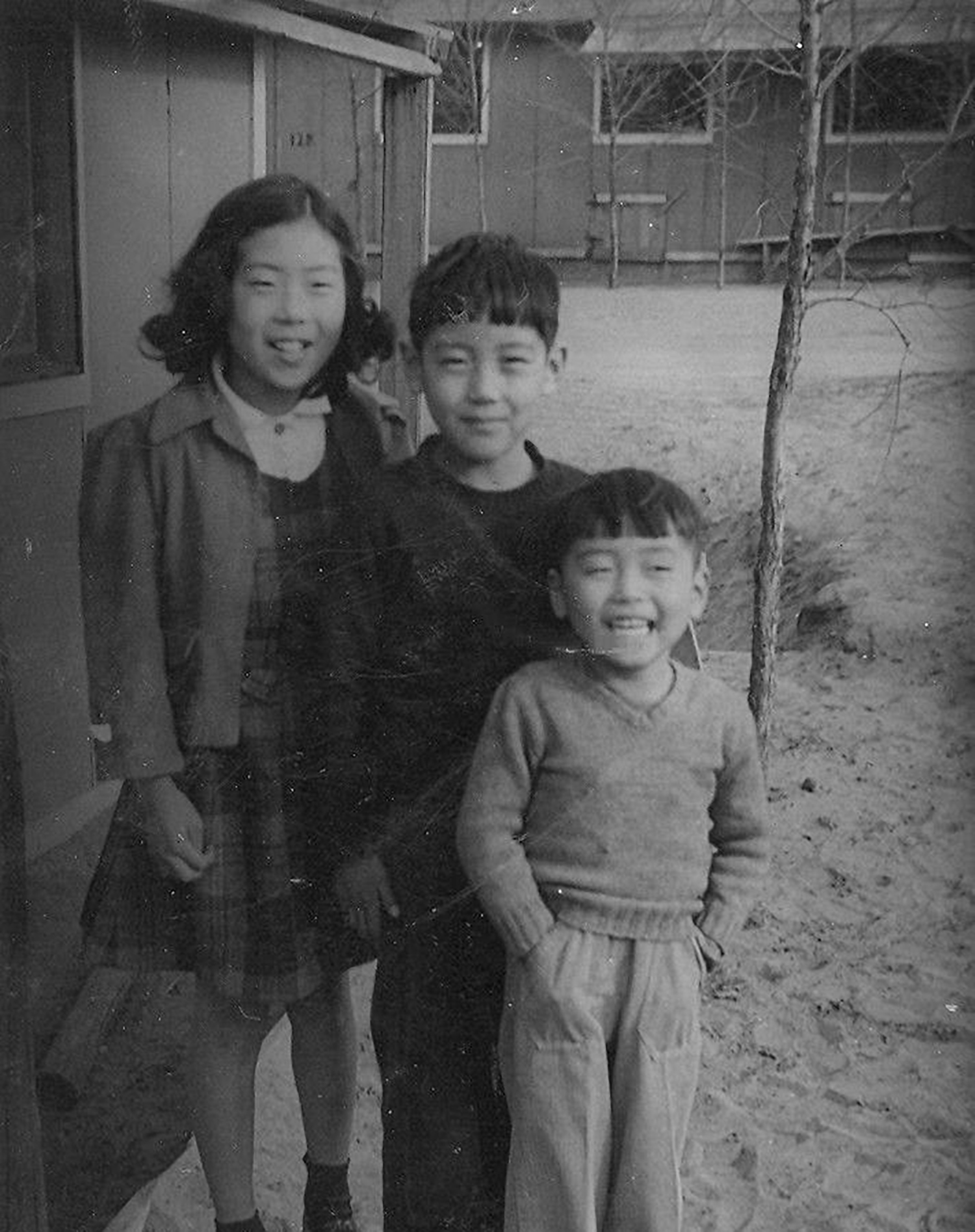

From left to right: Kumiko, Hisao and Kunio in front of their barrack (12K-12E) at Amache. Courtesy of the Homma Family Collection.

Listen to this portrait.

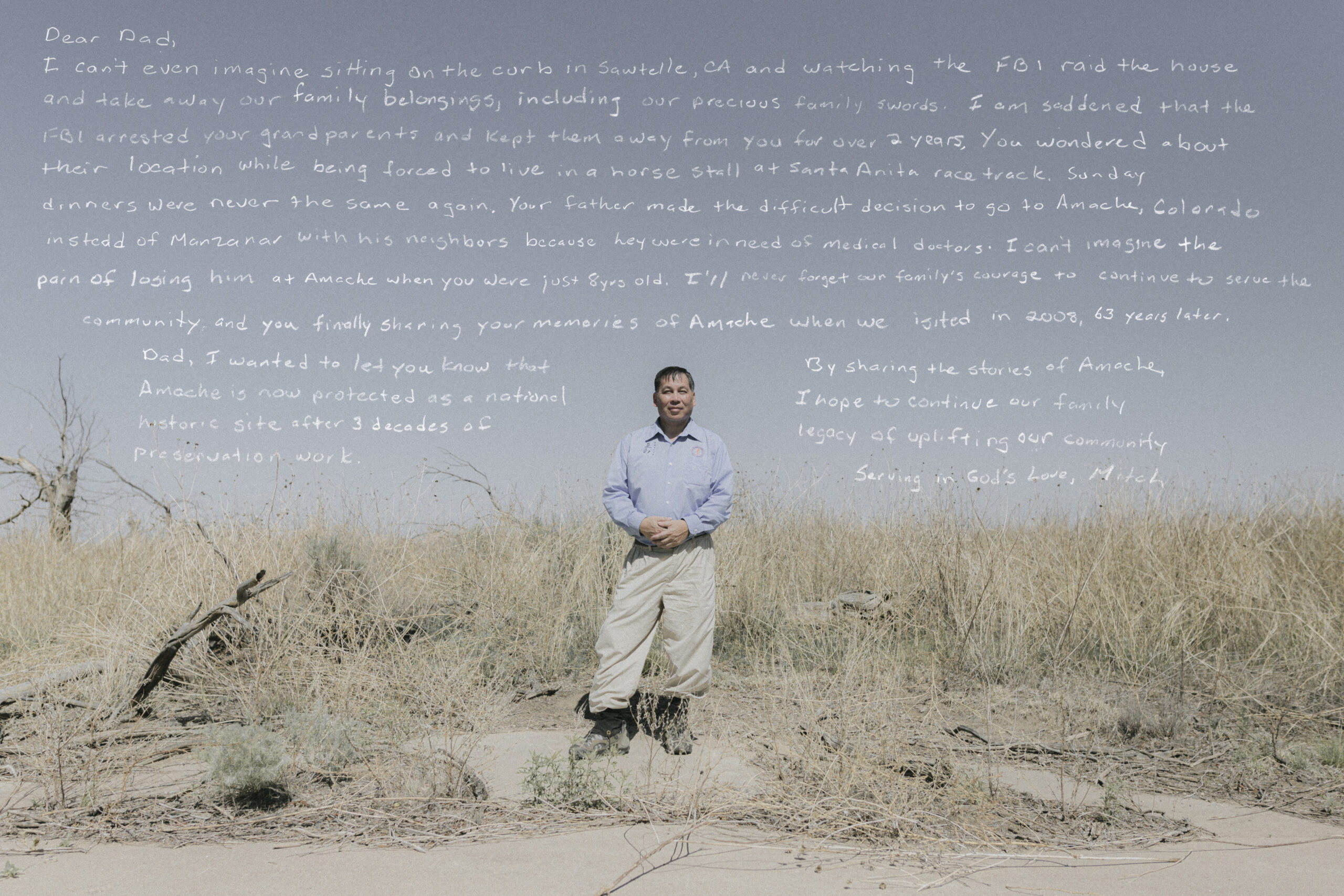

Mitch Homma

Sansei

Mitch Homma is the son of Hisao Homma. He was born and raised in Los Angeles.

Growing up, Mitch recalls that his family rarely spoke about their incarceration. “I grew up in one of our great-grandfather’s churches,” he says. “Everyone always asked me, ‘why were your grandparents arrested?’ And I didn’t know what they were talking about. I would ask my grandmother, and she just said they were taken away. She never told me directly that the F.B.I. came and arrested her parents.”

When the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 was passed, Mitch was a college student. His father left his reparations check untouched on his desk for weeks. “I started to push, telling him to do something with it,” Mitch says. “And his one comment back to me was, ‘My dad’s life was worth a lot more than $20,000.’”

Mitch began to uncover more about his family history after his grandmother’s passing in 2004, when he went to her home to sort through her belongings. There, he found his great-grandparents’ arrest records, along with a collection of Amache photos and a guestbook the Homma family kept in their barrack to record the names of visitors. Using these names as reference, Mitch started connecting with the people appearing in the photos. “That’s how I got involved in the preservation of Amache,” he says.

Four years later, Mitch and his father visited Amache together for the first time. “I don’t think I saw that much pain on his face ever in my life,” he says. “I felt like the worst son in the whole world, forcing him to come back to the place that took his father away.” Still, in the years following the pilgrimage, Hisao began to open up more about his family’s incarceration before he passed away in 2016.

Mitch now serves as President of the Amache Alliance, a nonprofit organization that facilitates annual pilgrimages to the Amache National Historic Site. “We’re trying to piece the community back together,” he says. “Serving other people, I think that’s our family legacy.”