“On the other side of the fence, African American men and women […] had burlap sacks hanging on their shoulders for the cotton they picked as they sang spiritual songs together in beautiful harmony. Papa and I stood under a tree so as to be hidden from them and the rifled soldiers who stood guard above us in a high tower close to the cotton fields.”

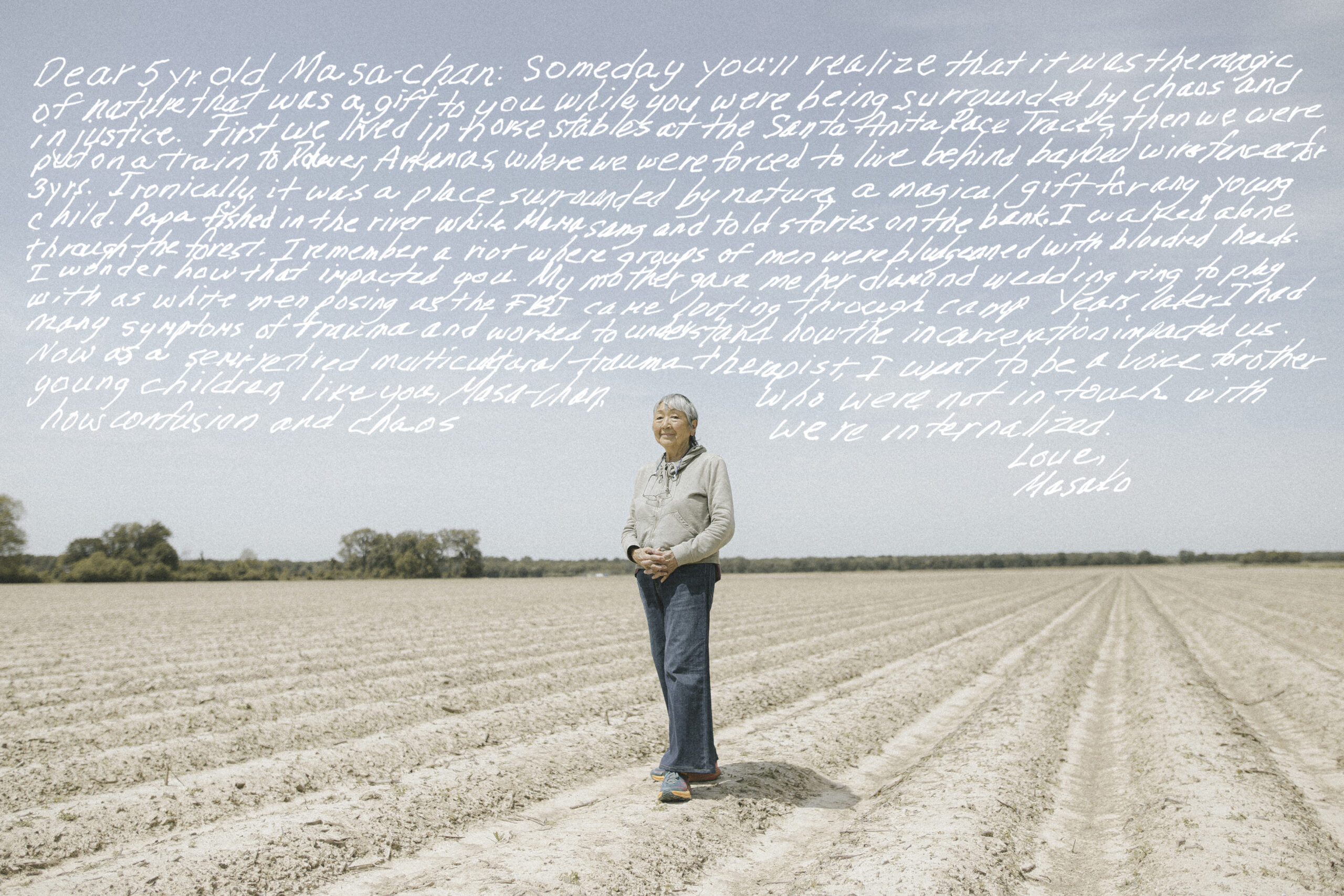

— Masako Endo Guthrie

Listen to this portrait.

Masako Endo Guthrie

Nisei

Masako Endo Guthrie was born in downtown Los Angeles between two Issei parents who ran a local hotel. She was five years old when Executive Order 9066 was issued and she and her family were sent to the Santa Anita Assembly Center.

Upon their arrival, Masako and her family were herded through gates where soldiers stood guard with rifles. “My little hands were wrapped around [my mother’s] thighs, holding on to her tightly,” she says. “My mother was crying. My father was expressionless.” Masako’s family were detained in Santa Anita Assembly Center for several months before they were sent to Rohwer, where they spent the next three years.

The swamps of Arkansas were drastically different from the bustling streets of downtown Los Angeles, where Masako grew up. “My father fished in a tributary of the Mississippi River while my mother […] sang Japanese songs and told traditional children’s fairytale stories, like Momotaro and Urashima Taro,” she says. “The irony is that my mother was very protective and preoccupied with me in downtown Los Angeles because she didn’t think it was safe, but in the internment camp, […] she could just let me be free.” It wasn’t until Masako began to seek therapy as an adult when she realized that she had internalized other memories from camp, like bloody altercations between incarcerees and men posing as F.B.I. agents visiting her family’s barrack to “collect” jewelry and other valuables. Whenever they came by, her mother would covertly hand her valuables to play with in the sandbox—like her diamond wedding ring—to avoid confiscation.

One afternoon, Masako and her father ventured to the border of the camp premises. “On the other side of the fence, African American men and women […] had burlap sacks hanging on their shoulders for the cotton they picked as they sang spiritual songs together in beautiful harmony,” she says. “Papa and I stood under a tree so as to be hidden from them and the rifled soldiers who stood guard above us in a high tower close to the cotton fields.”

After the war, Masako and her family moved to the Truman Boyd Manor housing projects in Long Beach. Eventually, they were able to save enough money to move back to their hometown of downtown Los Angeles. Masako is a retired trauma and somatic therapist.

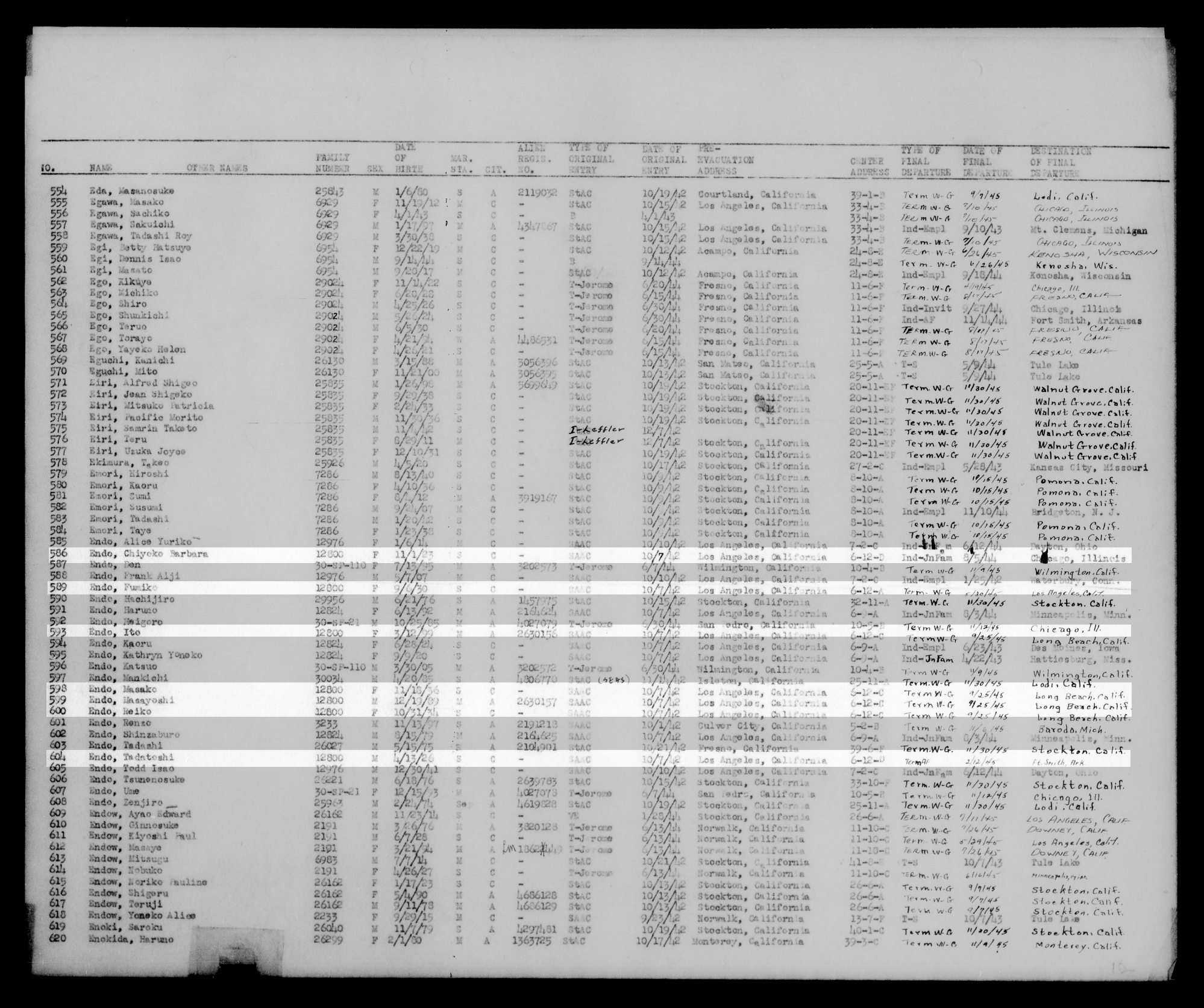

Masako’s information as it appears in the Final Accountability Roster for Rohwer. Courtesy of Densho Encyclopedia.

Listen to this portrait.

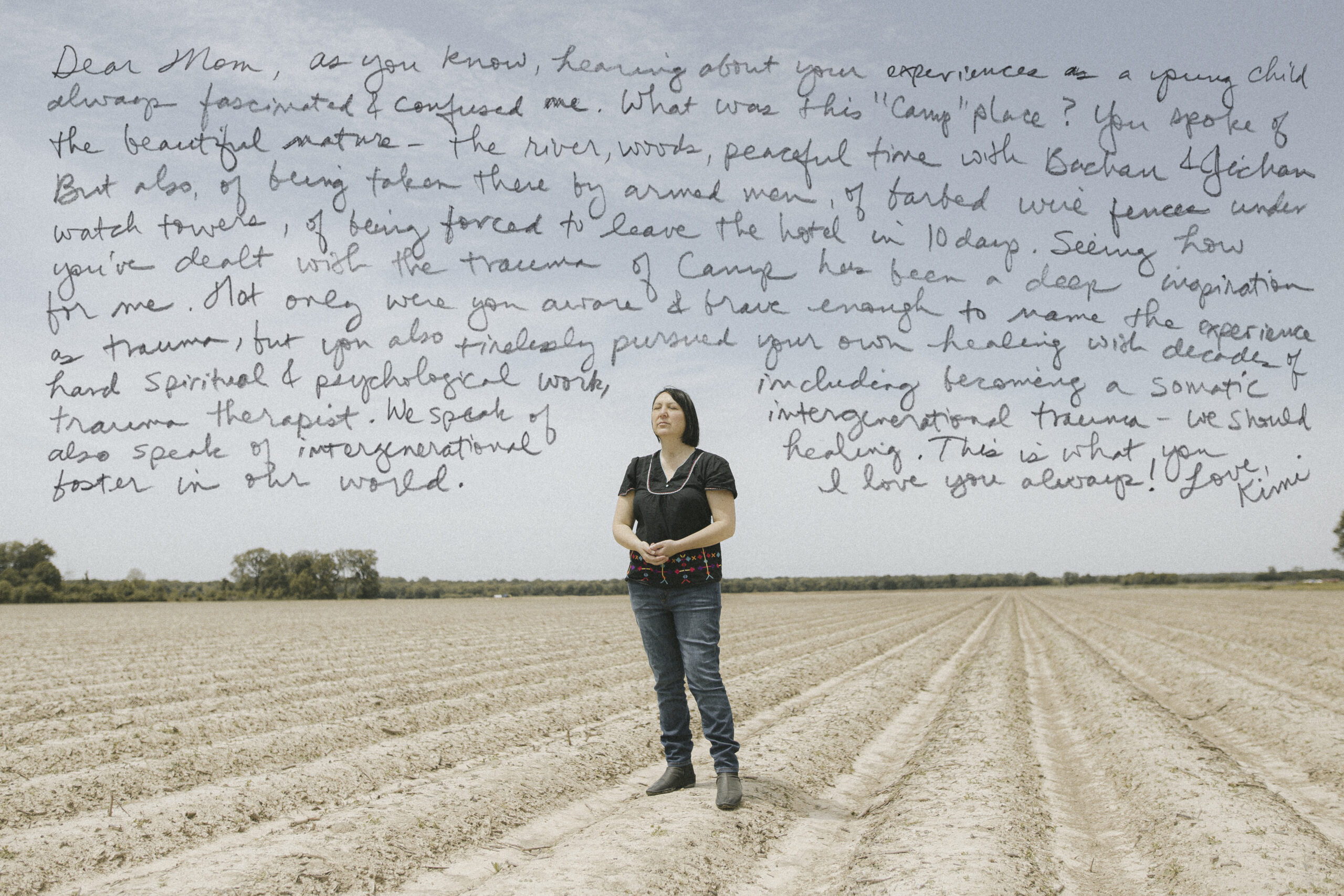

Kimiko Guthrie

Sansei

Kimiko Guthrie was born in San Francisco, CA and raised in Berkeley, CA. She is the daughter of Masako Endo Guthrie.

Growing up, Kimiko says her mother spoke openly about her incarceration. “A lot of nice memories actually, which was sort of confusing. She really loved being in nature, and her first introduction to nature was going to camp,” she says. “But then, of course, there were also flashes of seeing signs that said ‘No dogs or Japs allowed’, […] men with guns watching them. So on the one hand, these pleasant memories. But on the other hand, this darkness as well.”

In 2020, Kimiko published her first novel Block Seventeen, a fictional story about a mixed heritage Japanese American Sansei woman whose life begins to unravel as she is haunted by her ancestral past of wartime incarceration.

Although Kimiko grew up hearing stories about camp, it wasn’t until conducting research for her novel that she learned about certain aspects of the U.S. government’s use of surveillance and intimidation tactics against Japanese Americans. “One of the phenomena that I didn’t know about […] was the F.B.I. coming into neighborhoods right after Pearl Harbor and taking away the men,” she says. “I had always grown up thinking that the reason the Japanese American community didn’t want to talk about camp was cultural. It was framed to me in a positive way: that we have our dignity and strength. But then I learned about how much silence was forced on the community from the outside. […] It wasn’t just an internal sort of cultural silence. It was a silence from terror.”

Kimiko says there are stark differences between Block Seventeen’s protagonist and her. “I wrote about a character whose mother was the opposite of my mom. [She] is in complete denial, to a poetic extreme. So my main character is very traumatized without realizing it,” she says. “But [my mother] was determined to heal from her trauma. […] She became a teacher to help kids and then now she’s a trauma therapist. She didn’t turn away from it. She processed her own experience and used her own wisdom to help others.”

“I had always grown up thinking that the reason the Japanese American community didn’t want to talk about camp was cultural. It was framed to me in a positive way: that we have our dignity and strength. But then I learned about how much the silence was forced on the community from the outside. […] It wasn’t just an internal sort of cultural silence. It was a silence from terror.”

— Kimiko Guthrie

Listen to this portrait.

Mariko Rath

Yonsei

Mariko was born in Walnut Creek, CA and raised in Oakland, CA. She is the maternal grand-daughter of Masako Endo Guthrie.

As a mixed heritage Japanese American, Mariko says she has struggled to define her racial identity. Although many of her peers view her as white, she has always felt a strong affinity to her Japanese heritage. “It took me the longest time to realize that I wasn’t half Japanese [like my mother]. I thought I was a carbon copy of her because I never knew my mom’s dad’s white side,” she says. “I was confused. I was like, ‘What? I’m Japanese.’”

Mariko learned about the camps through conversations with her mother and grandmother. “They would just say ‘camp’, so I was like, ‘why can’t I go to camp?’,” she says. “And then, I learned more about it.” Mariko says her grandmother was open to sharing her experiences, but her stories often came in fragments: quiet afternoons on the Mississippi River, meandering walks along the swamp, an infant sibling that died shortly after camp. “Unless I ask very specific questions, there will probably always be important details that I won’t know about,” she says.

Mariko says her mother and grandmother have taught her to meet life challenges with curiosity and compassion. “[My grandmother] is a very intelligent person and is able to articulate things very well and really go into depth. I think that’s because she experienced trauma and then did a lot of work to understand it, and then to help other people with it,” she says. “I’m a good friend, […] a good listener. I ask a lot of questions. I want to know about people. These are all aspects that I think I’ve learned from my grandma and my mom.”

“[My grandmother] is a very intelligent person and is able to articulate things very well and really go into depth. I think that’s because she experienced trauma and then did a lot of work to understand it, and then to help other people with it.”

— Mariko Rath

Listen to this portrait.

Kaela Reiko Rath

Yonsei

Kaela was born in Berkeley, CA, and raised in Oakland, CA. She is the maternal granddaughter of Masako Endo Guthrie.

Kaela first became aware of her family history around the age of four when her mother shared stories while writing her novel Block Seventeen. “She told me there were guards with guns and watchtowers,” Kaela recalls. “She told me how one time, men from the nearby town came posing as FBI agents, stealing people’s valuables.”

In 2023, Kaela made her first pilgrimage to Rohwer. “I was wondering how my grandmother was feeling,” she says. “She said it was unrecognizable. It surprised me how different it was from our old pictures.”

While Kaela says it’s difficult to put into words what she learned from her visit, knowing her family history has profoundly shaped her. “I’ve inherited a feeling that it’s important to know your family history,” she says. “And when that history is negative, it’s still important to know it so you can help prevent history from repeating itself.”