“He did it because his sister was still back in Japan, and his father said we have to go back and get her. It wasn’t a political decision for him—it was a personal one.”

— Paula Fujiwara, on why her father answered “no-no” on the loyalty questionnaire

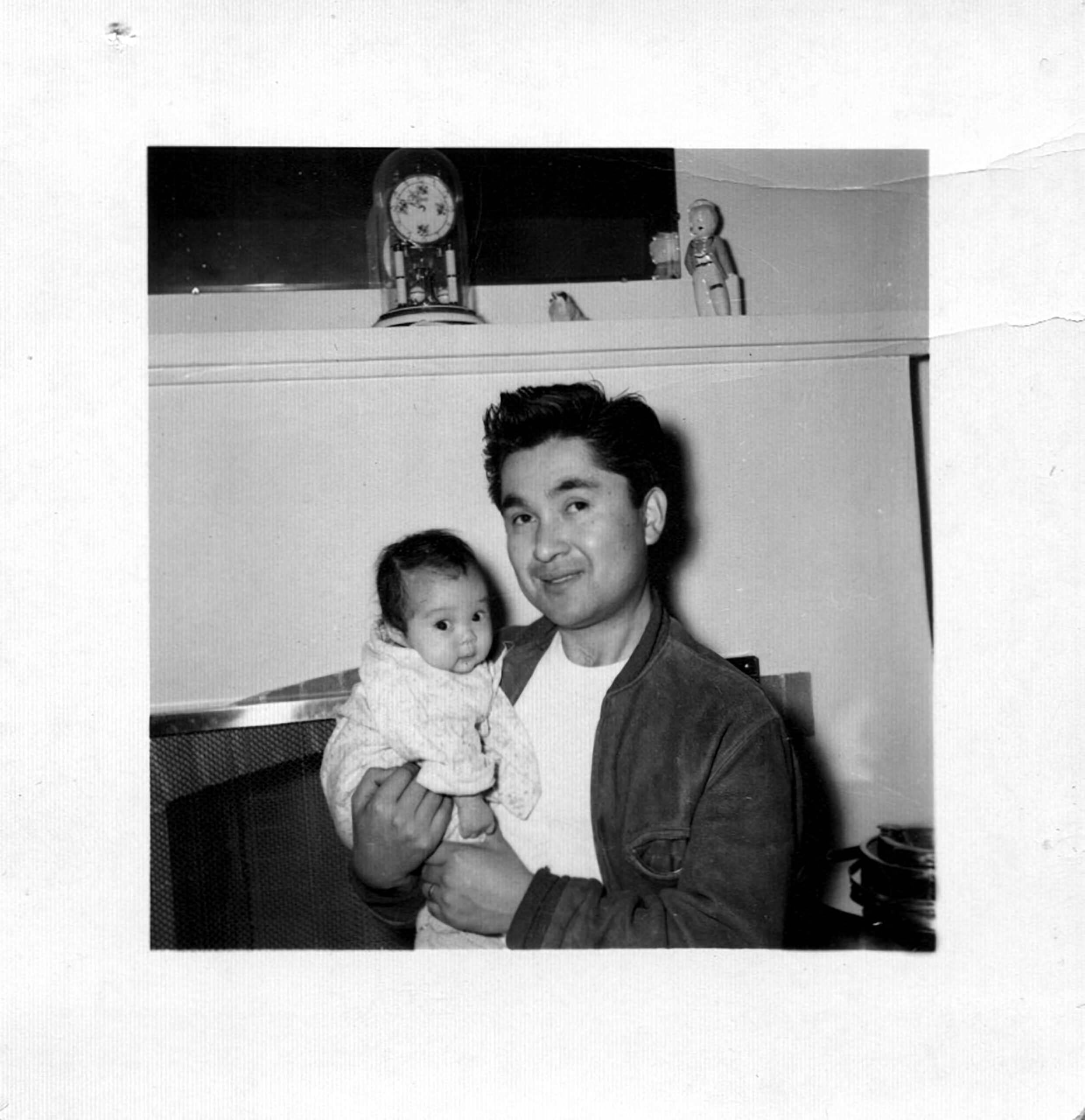

Kiyoshi Banard Fujiwara

Nisei/Kibei

Kiyoshi Fujiwara was born to two Issei parents in Sacramento, CA. When he was five years old, his mother passed away, and he and his sisters Dorothy and Harriet were taken back to Japan by their father to be raised by their uncle’s family. Kiyoshi spent the next 12 years in Hiroshima, Japan until he returned to the U.S. to rejoin his father in 1940.

The following year, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. Kiyoshi and his father were displaced from their home in Sacramento and sent to the Sacramento Assembly Center before being transferred to Tule Lake.

When the loyalty questionnaire was distributed in 1943, Kiyoshi answered “no” to Question 27 and Question 28. “He did it because his sister was still back in Japan, and his father said we have to go back and get her,” says his daughter Paula. “It wasn’t a political decision for him—it was a personal one.” Fearing that answering “yes” would prevent them from ever reuniting with their family in Japan, Kiyoshi’s father encouraged him to make the difficult decision to renounce his U.S. citizenship and prepare to return to Hiroshima after the war.

However, on August 6, 1945, the U.S. dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Kiyoshi’s sister survived the bombing, but his family urged him not to return. Without U.S. citizenship and with no place to live in decimated Hiroshima, Kiyoshi reached out to civil rights attorney Wayne M. Collins, who was helping renunciants restore their citizenship at the time. “He reached out to Wayne Collins, and said, ‘I made a mistake. I didn’t know what I was doing,’” says Paula. Thirteen years after the war ended, Kiyoshi was finally able to reclaim his U.S. citizenship in 1958.

After returning to Sacramento, Kiyoshi spent the next three decades working as a draftsman while raising a family with his wife, Eiko. He passed away during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Per his request, a portion of his ashes were laid to rest in a family graveyard in Hiroshima.

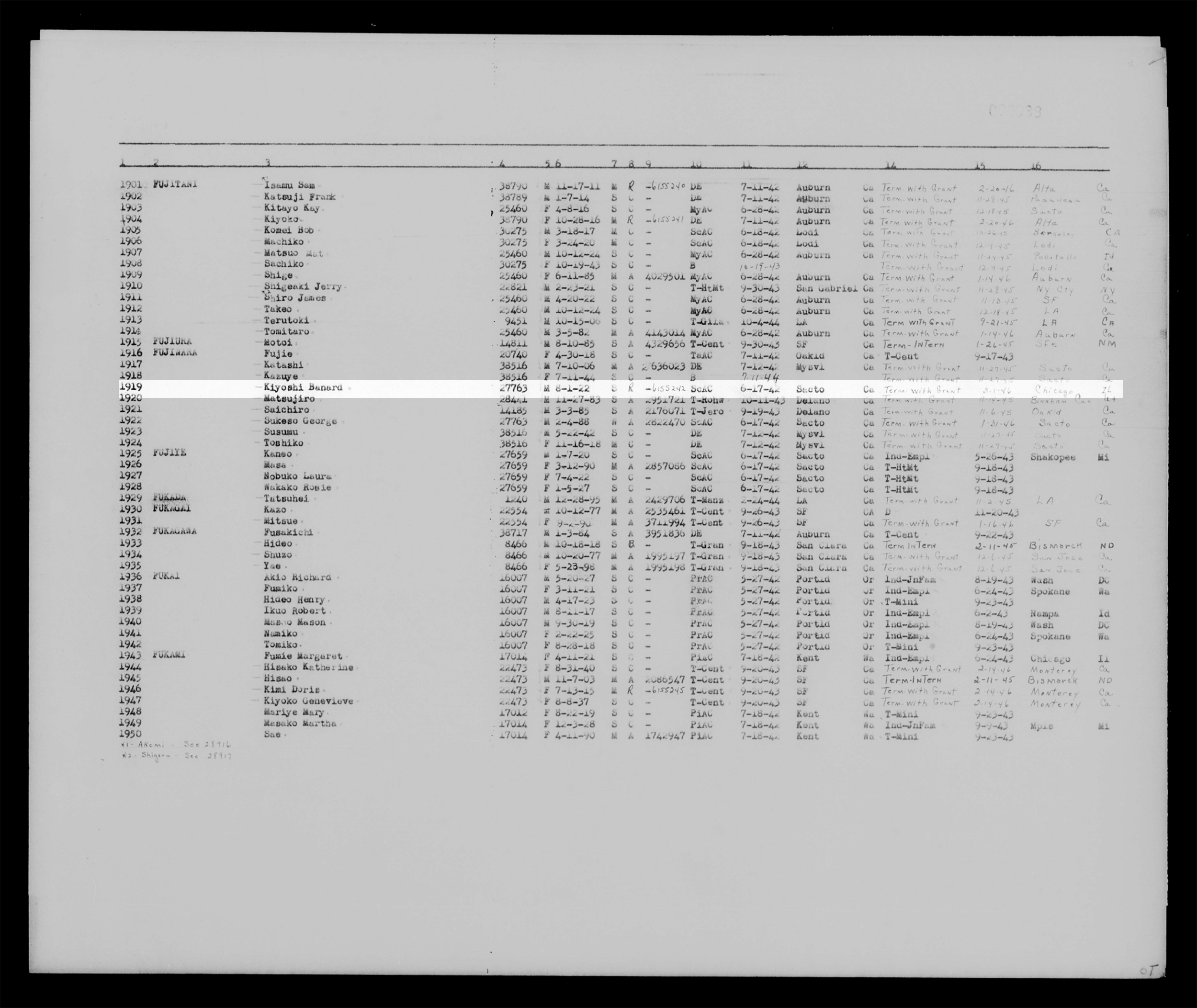

Kiyoshi’s information as it appears in the Final Accountability Roster for Tule Lake. Courtesy of Densho Encyclopedia.

Listen to this portrait.

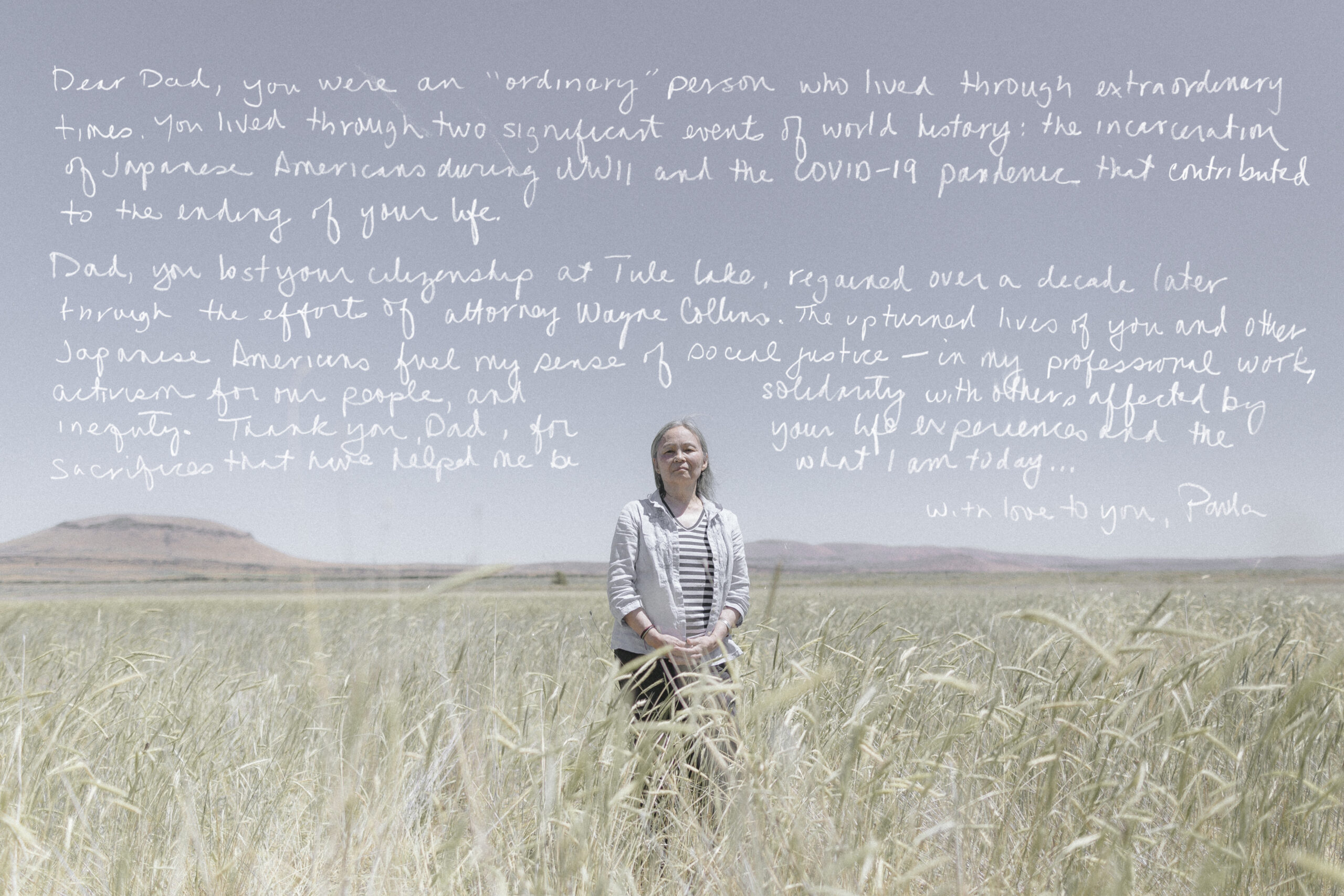

Paula Fujiwara

Sansei

Paula Fujiwara is the daughter of Kiyoshi Banard Fujiwara. She was born and raised in Sacramento, CA.

Growing up, Paula says her father spoke openly about his incarceration at Tule Lake. However, as she sorted through his belongings after his death in 2020, she discovered she only knew part of his story. “We were going through the boxes and then I found this one box that said Renunciation Papers,” she says. “And there was his whole story.”

In the box, she found letter exchanges between her father and Wayne M. Collins, requesting to restore his U.S. citizenship. She also found evidence that her father—formerly a dual citizen of the U.S. and Japan—had voluntarily renounced his Japanese citizenship after restoring his U.S. citizenship. “It was a letter from the consulate saying, ‘Dear Mr. Fujiwara, we understand that you want to renounce your citizenship from Japan. We’ve taken it off, and your name is off the koseki,” she says. “It was a formal announcement that you no longer exist, basically.”

“I know that a lot of Tuleans say that they were ashamed to say that they were no-no’s,” says Paula. “I never felt that in my family.” However, Paula hadn’t known her father was a renunciant or that he had faced the risk of deportation until after his passing. “[My father] was obeying his father who said, ‘We’re going back to Japan.’ He was not a Minoru Yasui or Gordon Hirabayashi. He was not one of these heroes. He was your average Joe,” she says. “The question for me is: who writes history?”