“You have two strikes against you: first, you are Japanese, and second, you are a woman.”

— Sue’s father to young Sue

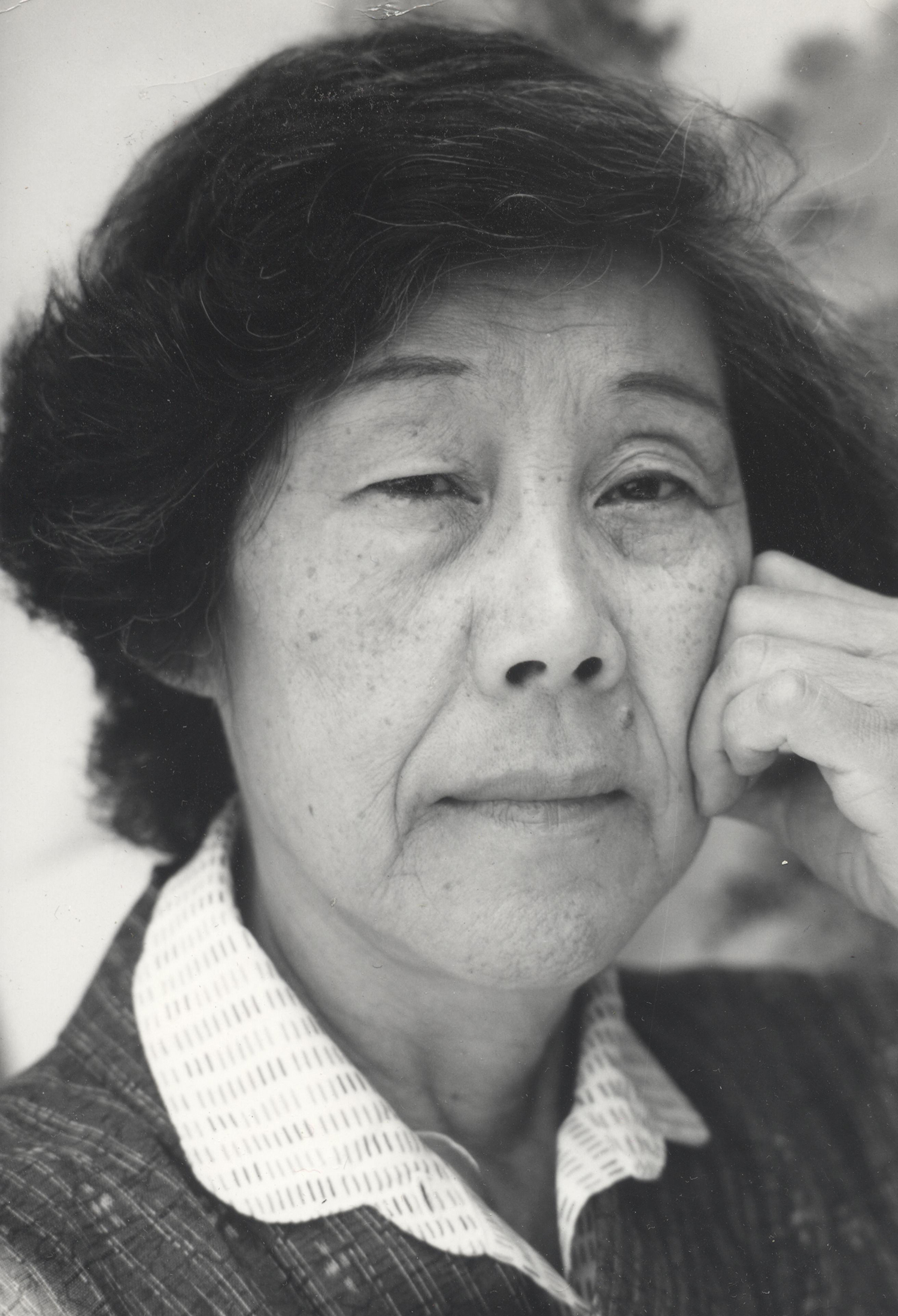

Sue Kunitomi Embrey

Nisei

Sueko Kunitomi Embrey—known as “Sue”—was born in Little Tokyo, Los Angeles, to Issei parents from Okayama Prefecture, Japan. When she was 14, Sue’s father died in a truck accident, leaving her mother to raise her and her seven siblings alone. Over the next several years, Sue’s mother saved enough to buy a small grocery store. However, after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor and the issuance of Executive Order 9066, she was forced to sell the store at a substantial loss as they prepared for “evacuation.”

Sue and her family were sent to Manzanar less than a year after her high school graduation. Sue contributed to the war effort by weaving camouflage nets and became the managing editor of the camp newspaper, Manzanar Free Press. In 1943, she obtained leave clearance as part of the resettlement program and briefly worked in Madison, WI before joining her two brothers in Chicago in 1944.

By the time the loyalty questionnaire was distributed, Sue’s family was scattered across the country: Sue was in Chicago, while her brother was at Heart Mountain in Wyoming with his wife’s family. Although Sue’s mother felt pressure from other incarcerees to answer “no” to Question 27 and Question 28, she ultimately answered “yes,” hoping to avoid deportation to Japan and keep the family together.

After the war, Sue returned to California to care for her mother and began working with the Los Angeles County Department of Education, later transferring to the Health Department. Politicized by her incarceration, Sue supported the Progressive Party candidate Henry Wallace’s presidential campaign.

In 1950, Sue married Garland Embrey, with whom she had two children. While balancing her roles at the Health Department, her advocacy work, and her family responsibilities, Sue pursued her long-held dream of attending college, enrolling part-time at California State University, Los Angeles. She earned her B.A. in 1969, nearly 30 years after her high school graduation.

As a young girl, Sue’s father had told her, “You have two strikes against you: first, you are Japanese, and second, you are a woman.” She carried the weight of this statement until 1972, when she earned a Master’s Degree in Education from the University of Southern California. “Although no bells rang, nor bright lights flashed, there was only my mother’s delight and astonishment that I had gotten the diploma,” she recalled. Sue went on to work as a teacher for the Los Angeles Unified School District and advocated for workers’ rights through various organizations, including the United Teachers of Los Angeles, the Asian Pacific American Labor Alliance, United Farm Workers, and UCLA’s Labor Center. She also served on the Los Angeles City Status of Women Commission for 10 years and was part of the US Delegation to the UN Second World Conference on Women in 1980.

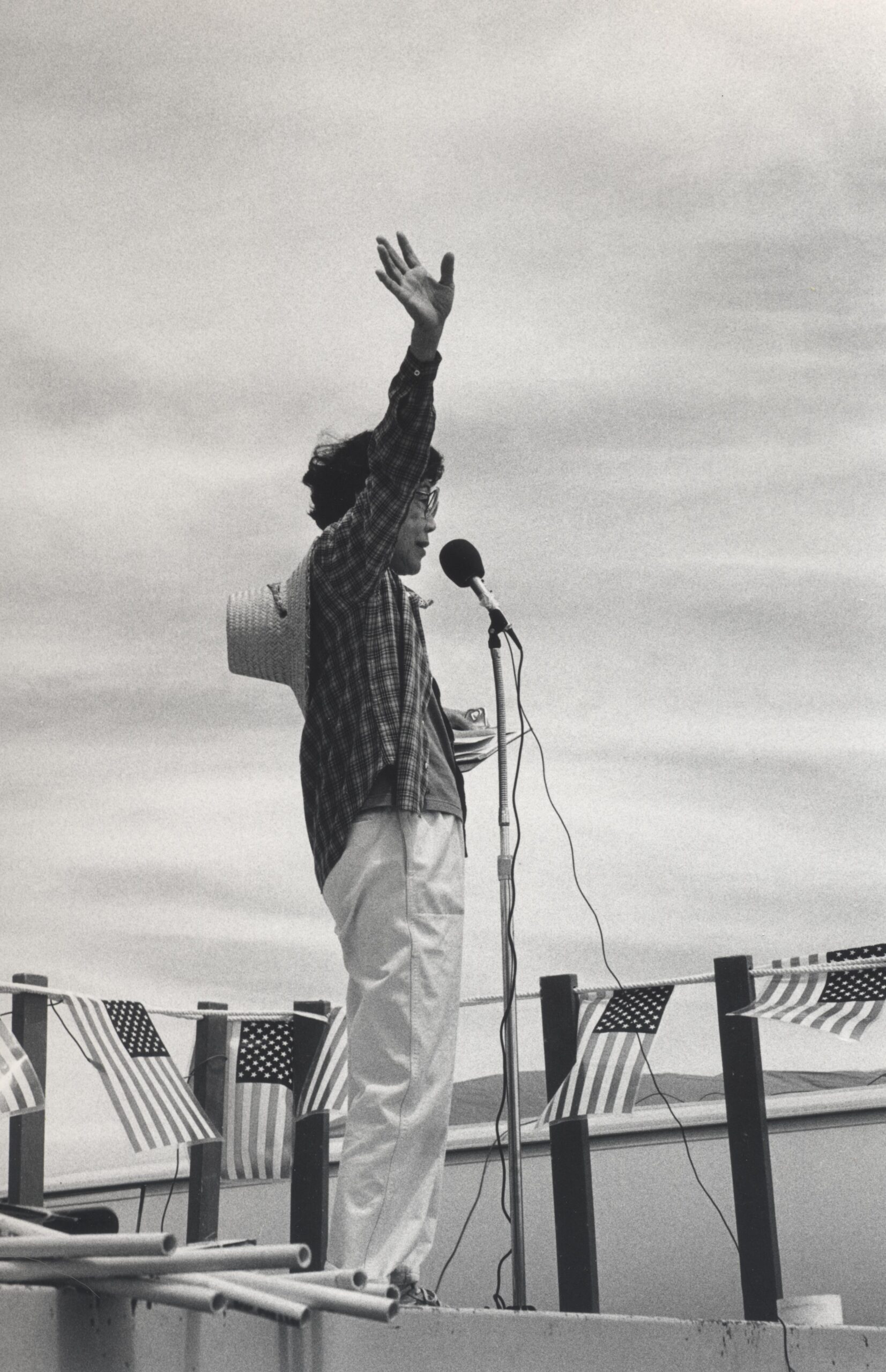

Sue returned to Manzanar in 1969 to participate in the first Manzanar Pilgrimage, speaking out publicly about the injustice her family endured, even in the face of criticism from some Japanese Americans. “I remember an elderly man confronted my mother on the street in Little Tokyo and berated her in Japanese,” recalls her son Bruce. “I asked her what he said, and she simply said, ‘He doesn’t want me to talk about Manzanar because it will bring shame to our community.’ The attacks on my mother ranged from calling her ‘un-American’ and bitter to labeling her an extreme left-wing radical trying to embarrass our government.”

Undeterred, Sue became co-chair of the Manzanar Committee and was instrumental in securing Manzanar’s designation as a State Historic Landmark in 1972, a National Historic Landmark in 1985, and a National Historic Site in 1992. While lobbying for the creation of the Manzanar National Historic Site Interpretive Center, she said, “The Interpretive Center is important because it needs to show the world that America is strong as it makes amends for the wrongs it has committed.” Sue organized the annual Manzanar Pilgrimage for 37 years until her passing in 2006.

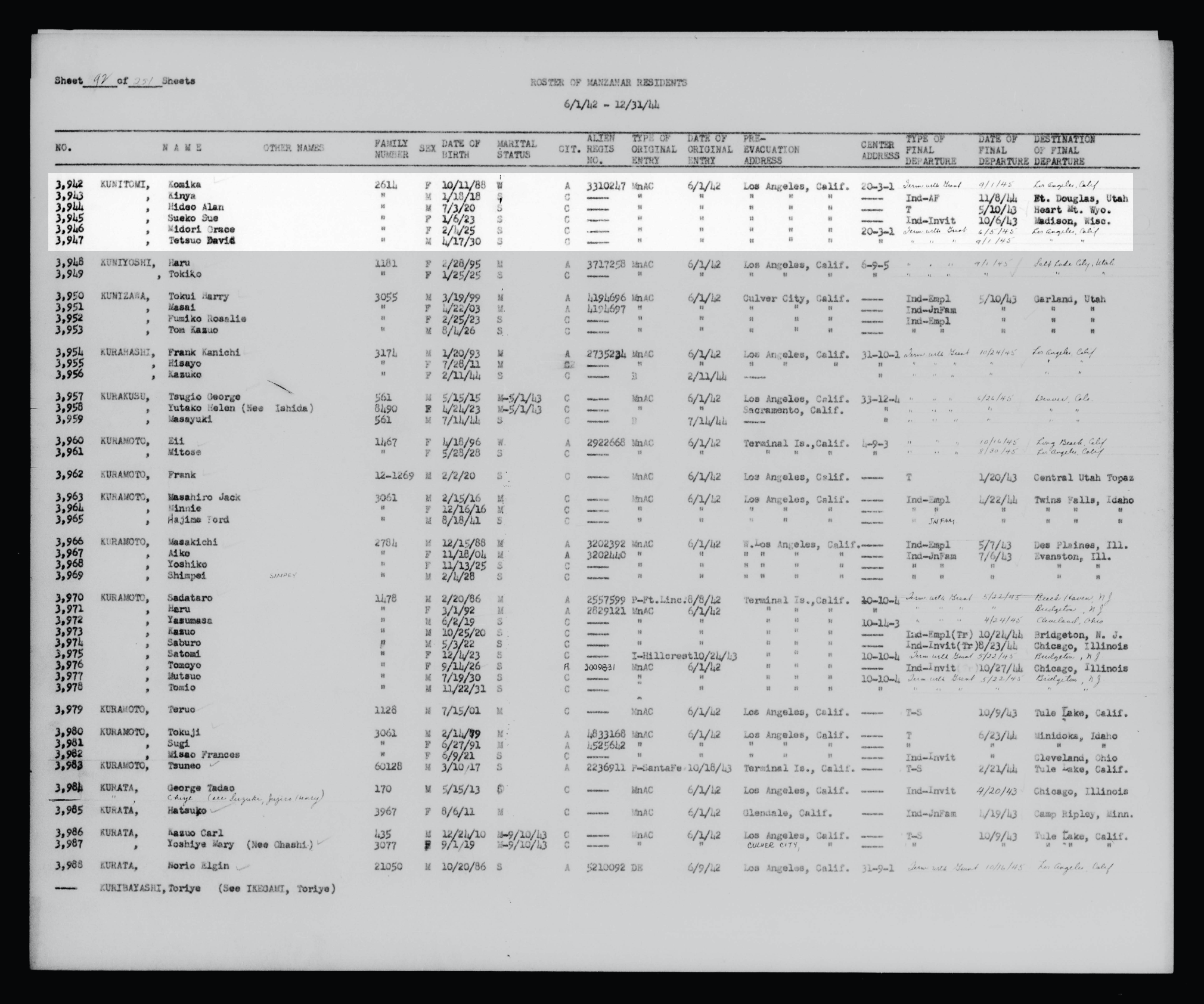

Sue’s family information as it appears in the Final Accountability Roster for Manzanar. Courtesy of Densho Encyclopedia.

Listen to this portrait.

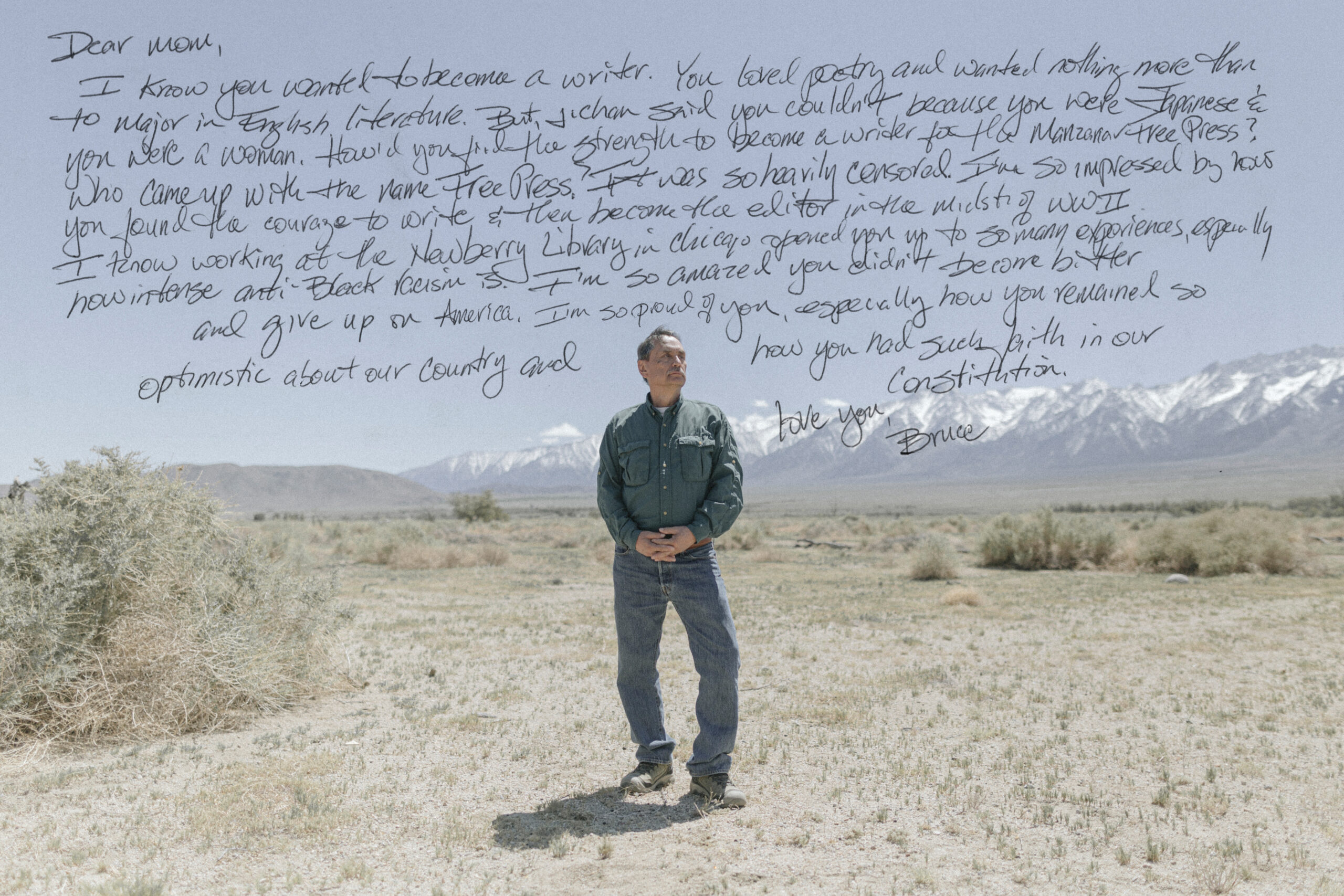

Bruce Embrey

Sansei

Bruce Embrey is the son of Sue Kunitomi Embrey. He was born and raised in Los Angeles.

Bruce first became aware of his family history when he overheard his mother sharing her wartime experiences with friends when they lived near Taos Pueblo in New Mexico. At that time, the Puebloans were embroiled in a campaign to reclaim Blue Lake, their sacred ritual site. “We lived in a small adobe house next to the reservation owned by friends from the Pueblo,” Bruce recalls. “I remember during [these] tumultuous times, my mother talking about her wartime experiences with friends. Then […] with my mother returning to Manzanar in 1969, I was completely surrounded by it every day.”

Born to a Japanese American mother and a Texan father, Bruce was part of a stark minority of mixed-heritage children. “Anti-miscegenation laws in California weren’t repealed until 1948—only 10 years before I was born—so it’s not surprising we were a small minority,” he explains. “I got [questions like] ‘what are you’ or ‘where are you from’ all the time.”

Bruce says his family history has had a profound impact on who he is today. “Camp has made me determined to hold America to its promises, to reform the fundamentally undemocratic features of our society,” he says. “I see being a loyal American as being a person thoroughly dedicated to the pursuit of equal justice, full and consistent democracy for all peoples no matter their origins, religious beliefs, sexual orientation, or gender identity.”

Today, Bruce carries on Sue’s legacy as co-chair of the Manzanar Committee. He continues to organize the annual Manzanar Pilgrimage in her memory.

“Camp has made me determined to hold America to its promises, to reform the fundamentally undemocratic features of our society.”

— Bruce Embrey

Listen to this portrait.

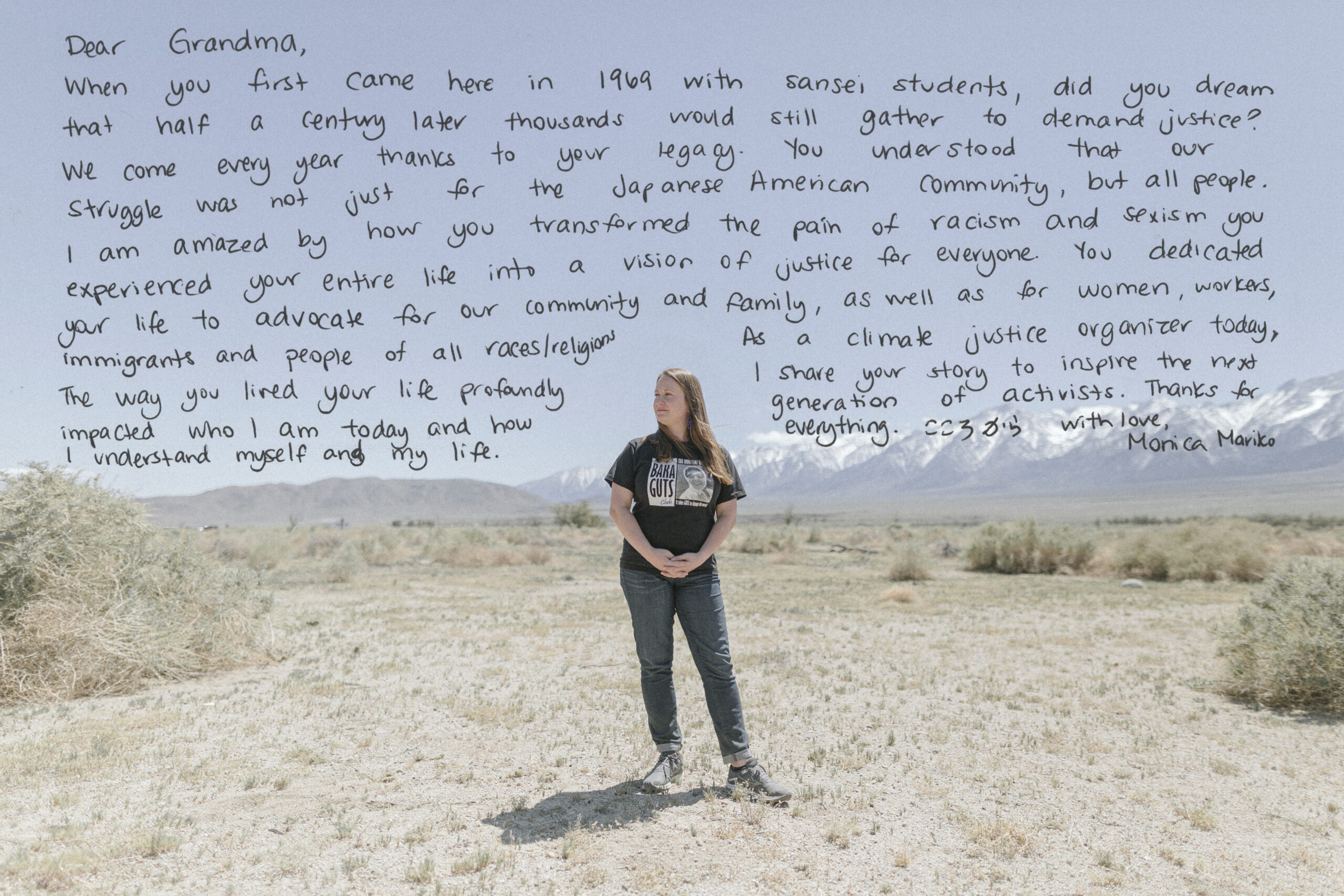

Monica Mariko Embrey

Yonsei

Monica Mariko Embrey is the paternal grand-daughter of Sue Kunitomi Embrey. She was born and raised in Chicago.

Growing up, Monica was encouraged to celebrate her multi-racial heritage. “My parents raised me to be proud and strongly identify with all parts of my family: my Japanese-American and Chicana roots from my dad and German-American and Russian-American Jewish roots from my mom,” she recalls. “I have a memory from kindergarten of being assigned the task of decorating a paper doll with traditional clothing of our ancestors. I had to ask my teacher for four paper dolls, because I would not decorate only one limb with each part of my family’s heritage.”

Monica has regularly attended the annual Manzanar Pilgrimage since childhood, witnessing its evolution over the years—such as the inclusion of programs involving the Muslim and Arab-American communities after September 11. This experience has deepened her appreciation for her grandmother’s legacy. “As I entered college, I learned more about the challenges my grandmother faced in her decades of advocacy, including significant opposition rooted in anti-Asian racism as well as criticism from within the Japanese-American community rooted in fear of retaliation by the federal government,” she says. “One of the most important lessons that I learned from my grandmother is that being an American means advocating for liberty and justice for all.”

Today, Monica continues Sue’s legacy as a member of the Manzanar Committee and works as a climate justice organizer in Los Angeles.