“I am signing under protest, because I believe myself to be an American citizen.”

— George Narita

George Narita

Nisei

George Narita was born in Sacramento, CA and raised in Isleton, CA. He had just turned 21 the day before Japan attacked Pearl Harbor.

Shortly after the attack, the F.B.I. attempted to arrest his father, Masataro, who was a community leader involved in the Japanese Association of America. However, upon arriving at their home, they discovered Masataro was bedridden with a heart condition. “They didn’t arrest him right away, but they were watching him,” says his grand-daughter Akemi. “They were walking along the levee, watching their house all the time.” One day, when Masataro felt well enough to step outside, the F.B.I. took him away. He was imprisoned in several detention centers before being transferred to Fort McDowell Internment Camp, Lordsburg Internment Camp, and Santa Fe Internment Camp. George did not see his father again for the next two years.

A month after Masataro was taken, George, his mother Yoshi, and his four siblings were sent to Sacramento Assembly Center and transferred to Tule Lake. Now a “single” mother, Yoshi struggled to support her family. “The youngest son was running free with his friends. He didn’t have a father figure anymore,” says Akemi. “People remember [Yoshi] as being a cold person, but I wonder who she was before all of this—if that changed her.”

When the loyalty questionnaire was distributed in 1943, George and his brother Johnny answered “no” to Question 27 and Question 28. “George, as the new head of the family, felt some pressure to stay there for his family, instead of leaving for the military,” says Akemi. “They thought it would mean that they didn’t have to be drafted.”

Meanwhile, in Santa Fe Internment Camp, Masataro’s health was rapidly declining. Eventually, he was granted permission to reunite with his family in Tule Lake in February 1944. “I think it’s because they knew he was dying,” says Akemi. “He died in December of that year.”

When the President signed the Denaturalization Act of 1944, thousands of incarcerees renounced their U.S. citizenship, many in protest to their unconstitutional treatment during the war. That winter, George renounced his citizenship. Shortly after, the Department of Justice sent him an alien registration card along with a request for his signature to confirm receipt. On the signature line, he wrote, “I am signing under protest, because I believe myself to be an American citizen.”

On November 13, 1945, just two days before a ship carrying renunciants was set to leave for Japan, civil rights attorney Wayne M. Collins secured a court order preventing their deportation until they could appear before a judge. Over the next four months, the Department of Justice held administrative hearings at the Tule Lake Segregation Center. George and Johnny remained for the hearings while the rest of the family was released and moved to San Francisco. George and Johnny joined them in March of 1946.

For the next 13 years, George lived in the U.S.—his birthplace—as a resident alien. He worked in a mattress factory that was one of the few businesses that would hire Japanese Americans at the time. With the help of Wayne M. Collins, George was finally able to restore his U.S. citizenship in 1958. He did not speak openly about his incarceration or renunciation before passing away in 2000.

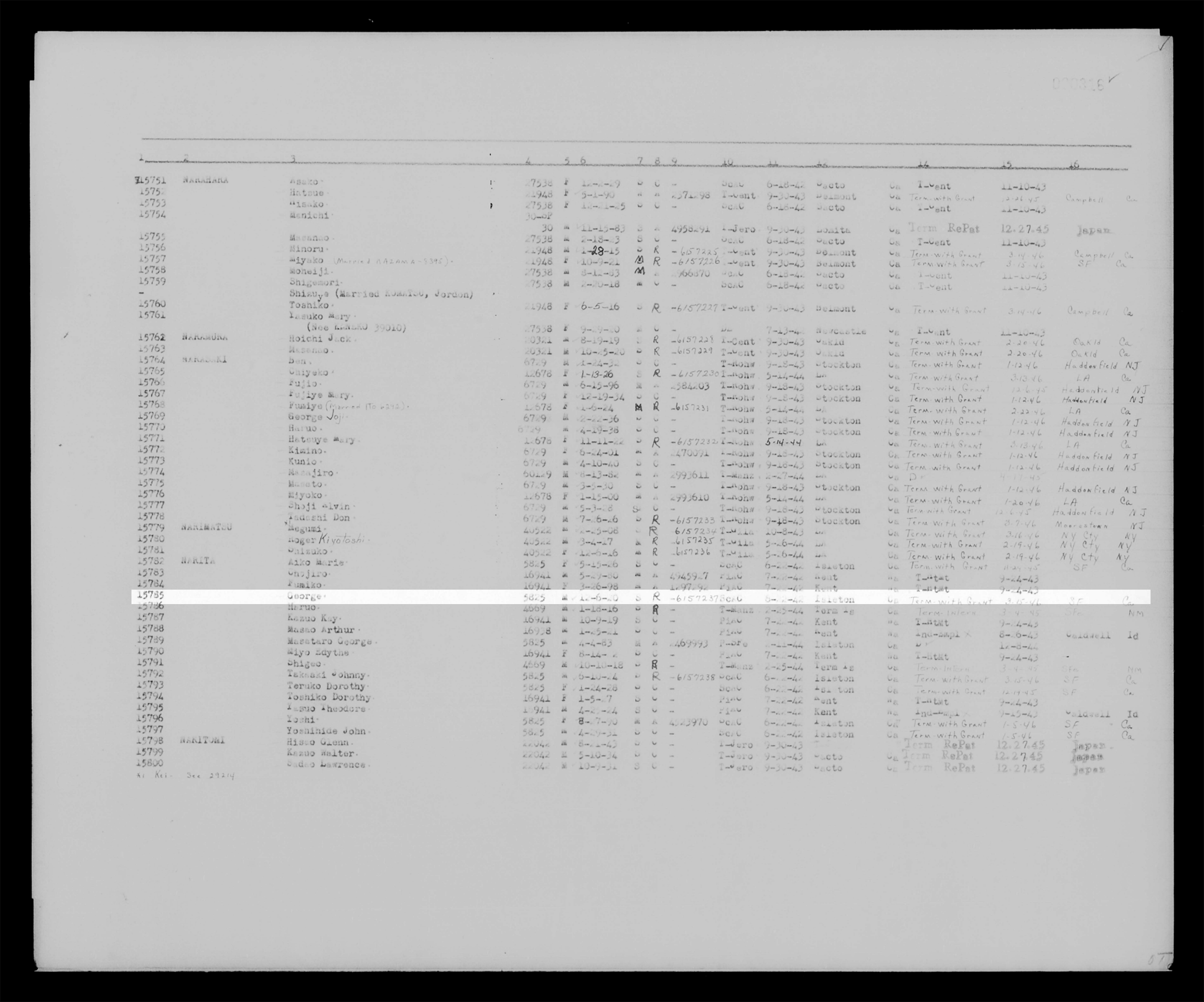

George’s information as it appears in the Final Accountability Roster for Tule Lake. Courtesy of Densho Encyclopedia.

Listen to this portrait.

Akemi Johnson

Yonsei

Akemi Johnson is the maternal grand-daughter of George Narita. She was born in Oakland, CA and raised in Marin County, CA.

Growing up in a predominantly white community, Akemi did not always feel connected to her Japanese heritage. “My parents gave me and my siblings all Japanese names, but there wasn’t a lot of Japanese culture or language that we grew up with,” she says. “I think I really inherited the shame of being Japanese American and wanting to be white, wanting to assimilate.”

Her perspective began to shift in college. “It was a completely different environment where people’s identities were celebrated,” she says. “I felt safe to be who I am and to embrace this part of myself that I’d tried to downplay my whole life.” During her junior year, she decided to study abroad in Japan.

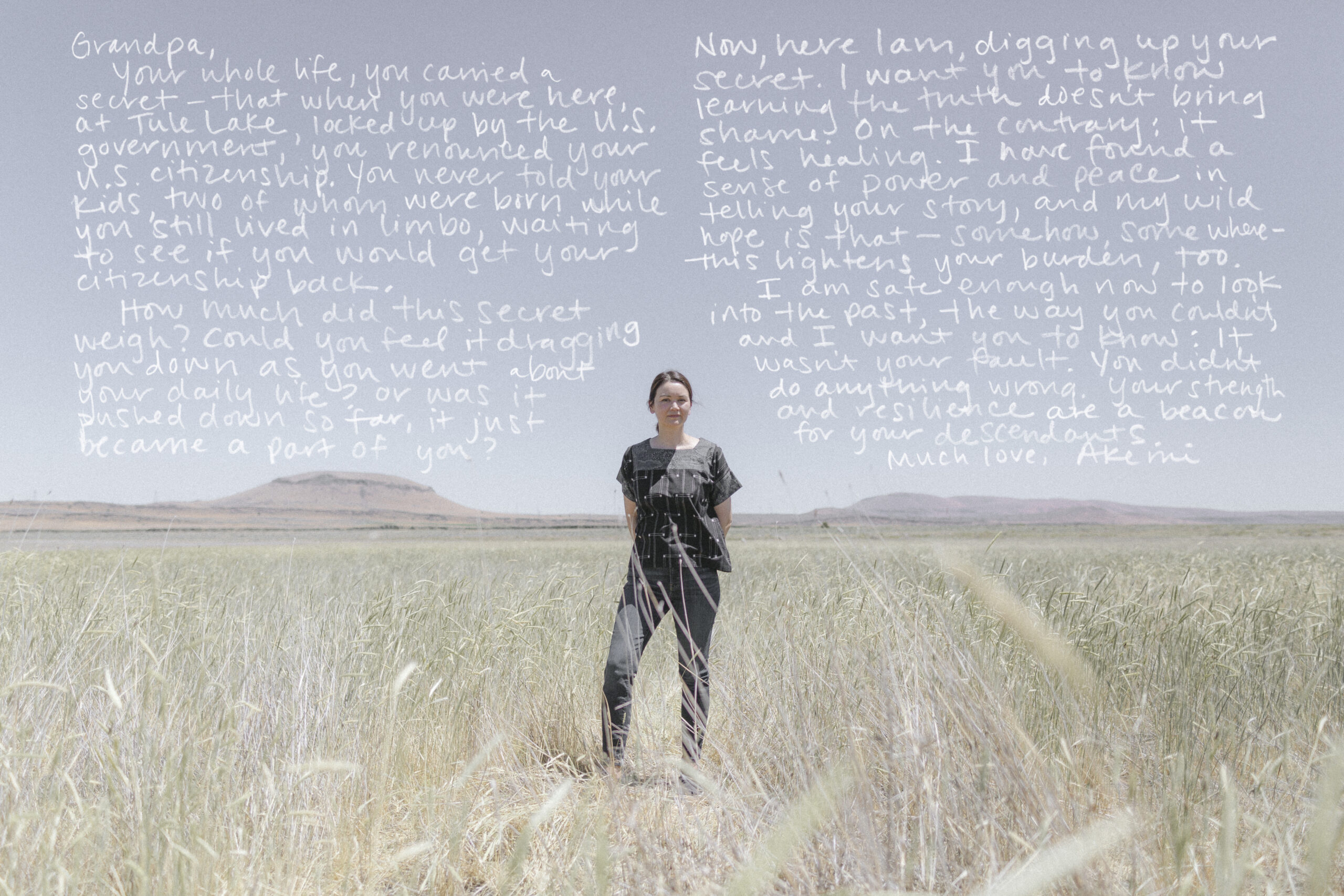

Although Akemi was aware of her family history from a young age, she only learned about her grandfather’s renunciation after his passing in 2000. “My mom and I were going through his things and found the paperwork from Wayne Collins and his alien registration card,” she says. “I had always believed this model minority story—that they went quietly, never complained, never protested. And then here he was, saying ‘I protest.’ It made me realize that I didn’t understand this story at all.”

Akemi is an author currently based in Sacramento, CA. Since 2020, Akemi has been researching her family’s history to write a book about renunciants like her grandfather. “So much of my life has been shaped by this history, and an attempt to heal from it,” she shares. “It feels empowering to confront that and find a different way of being in America.”