Located in the High Plains of southeastern Colorado, the Granada Relocation Center—known as Amache—had the smallest population out of the 10 War Relocation Authority concentration camps. The camp was named after Ameohtse’e, the daughter of O’kenehe, a prominent Cheyenne chief who was murdered during the Sand Creek Massacre. The name became more commonly used to prevent postal mix-ups between the town of Granada and the Granada Relocation Center.

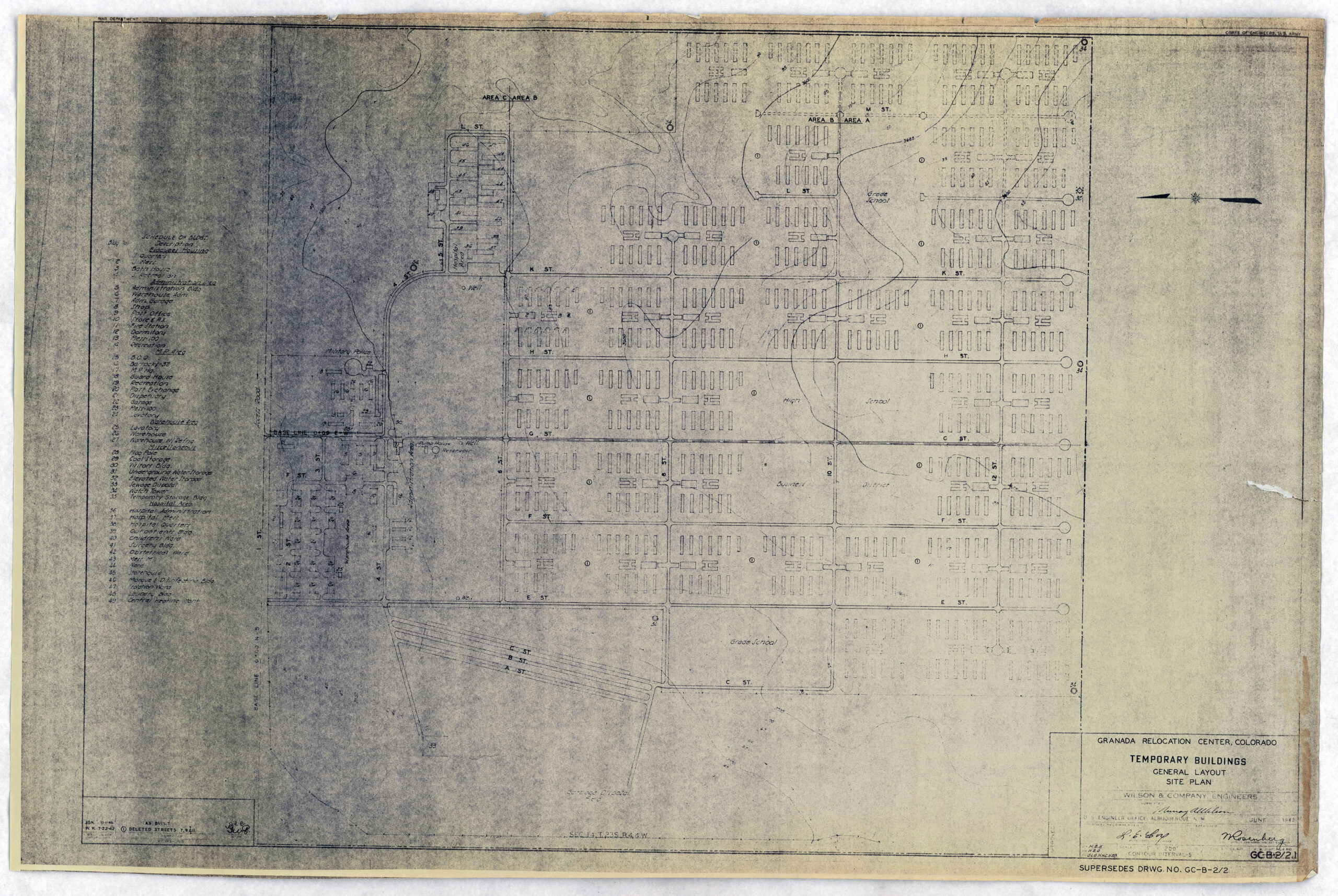

The War Relocation Authority‘s master plot plan for Amache. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

The concentration camp was situated on 10,500 acres of sandy prairie between the Rocky Mountains and the Great Plains. Summers were hot and dry, often accompanied by severe thunderstorms or tornadoes, and winters were bitter and cold with heavy snowfall. Choking dust storms were common year-round.

Incarcerees planted trees and communal gardens around their barracks to restore a sense of normalcy while detained in camp. June 20, 1943. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

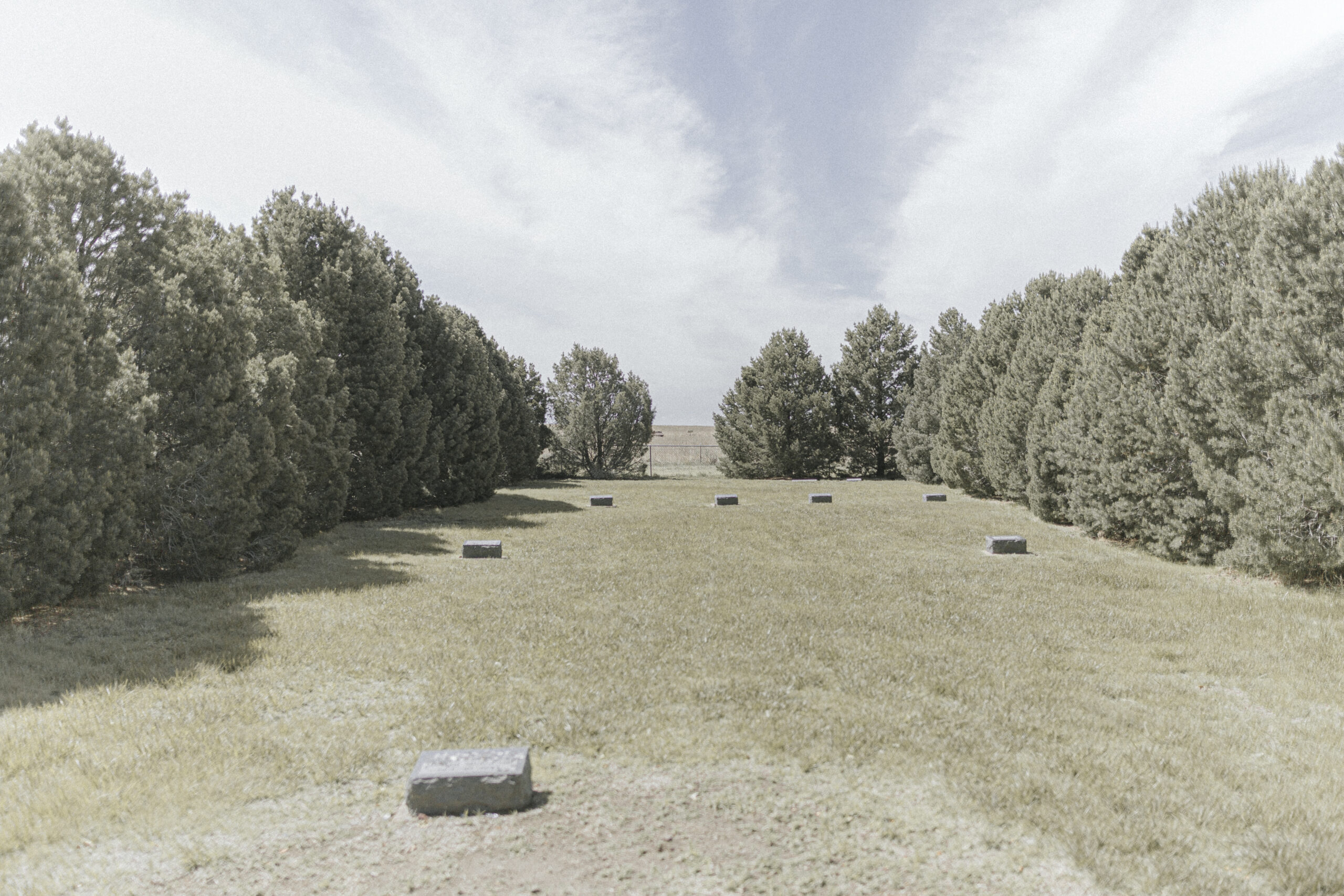

Building foundations, garden features and trees planted by incarcerees remain at the site today. June 24, 2024.

Incarcerees at Amache mainly came from three areas in California: the Central Valley, the northern coast, and southwest Los Angeles. Many had experience in farming and landscaping, and they used their skills to beautify the camp by cultivating communal gardens, installing decorative entryways around their barracks and planting rows of cottonwood and Siberian elm trees to provide much-needed shade during the hot summer months.

Some communal gardens—like this koi pond—incorporated traditional Japanese elements, like asymmetrical shapes, natural materials and shakkei, or “borrowed scenery” from the surrounding area.

A metal planter, likely handmade by an incarceree. Thanks to local researchers’ “catch-and-release” archaeological methodology, many camp artifacts like ceramics, cookware and gardening tools—even marbles that children used to play with—remain at the site today.

Unlike other camps, Amache was situated on land that was privately owned before the war. Much of this land was seized through condemnation, leading to friction between the War Relocation Authority and local residents. When construction of Amache High School—a high school for incarcerees—started in the summer of 1942, locals opposed it. The area, still recovering from the Dust Bowl, had seen little new construction for decades. Residents resented the cost of building a school specifically for Japanese American students. Although the high school was finished, plans for an elementary and middle school were eventually dropped.

Incarcerees visiting Granada, a town located within walking distance from the Amache concentration camp. Some local businesses—like Newman’s Drug Store, pictured here—sold Japanese items to attract incarcerees. Circa 1942-1945. Courtesy of the George Ochikubo Collection.

The building that housed Newman’s Drug Store today. Next to it is what used to be the Granada Fish Market, a business founded by Frank Tsuchiya, an incarceree who obtained an early release from Amache and used his connections from running a fish market in Los Angeles to bring sashimi grade fish and other coveted Japanese foods to Granada. June 24, 2024.

What made Amache distinct was its walking distance from Granada, a small nearby town. This allowed incarcerees to go shopping and partake in small indulgences like visiting a soda fountain outside of camp, unlike other War Relocation Authority camps. Initially, some local businesses were anti-Japanese, but they soon recognized the incarcerees as valuable customers. Edward Newman, a local businessman, rented a large building in Granada and stocked items that he thought would appeal to the incarcerees, like Japanese sake. He even employed incarcerees in his store and as a nanny. By 1945, the Amache High School yearbook was full of advertisements from local businesses.

An original recreational hall, which was removed from the site in 1946 to serve as a utility building, was returned to Amache in 2018.

Concrete foundations show that most of the barracks were 120′ x 20′ buildings divided into six apartment units. Each apartment was equipped with a coal-burning stove, as interpreted by the elevated square platform.

There were 29 residential “blocks” at Amache. Each block consisted of 12 barracks, a mess hall, a public laundry, a recreation hall, and a communal bath house, as pictured here.

What remains of the Amache Cooperative Enterprise, an incarceree-led community cooperative that once included a shoe repair shop, beauty parlor, optometry shop, and clothing store among other businesses. Even non-Japanese locals shopped for goods and services at the cooperative.

Amache had the lowest percentage of incarcerees who answered “no” to Question 28 on the loyalty questionnaire. After segregation hearings, only 125 incarcerees were transferred from Amache to the Tule Lake Segregation Center, while 993 incarcerees from Tule Lake were sent to Amache. In total, only 35 Amache incarcerees were repatriated to Japan.

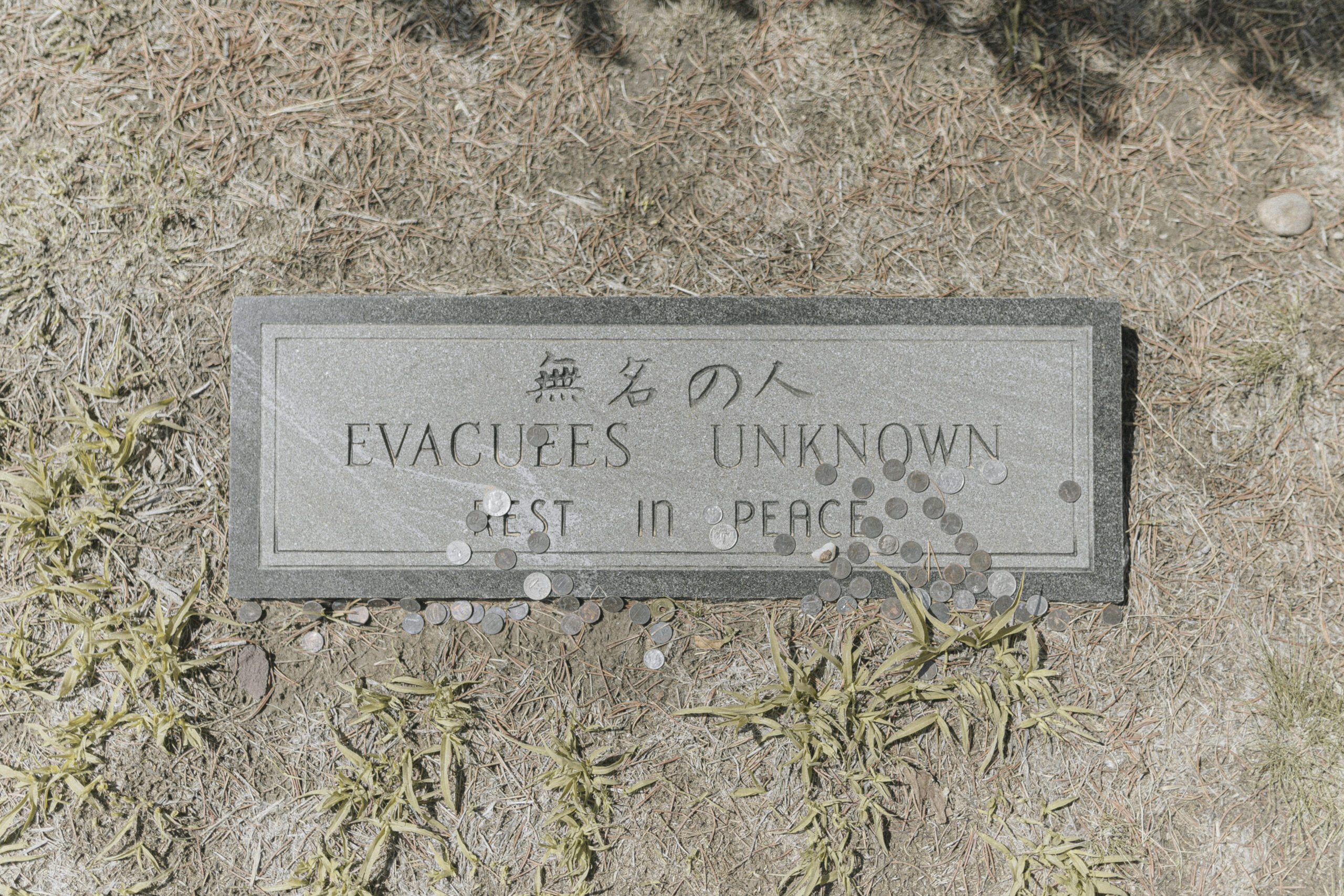

The cemetery includes 11 grave plots, ten with markers and one without. The unmarked grave plot is dedicated to incarcerees whose names are unknown.

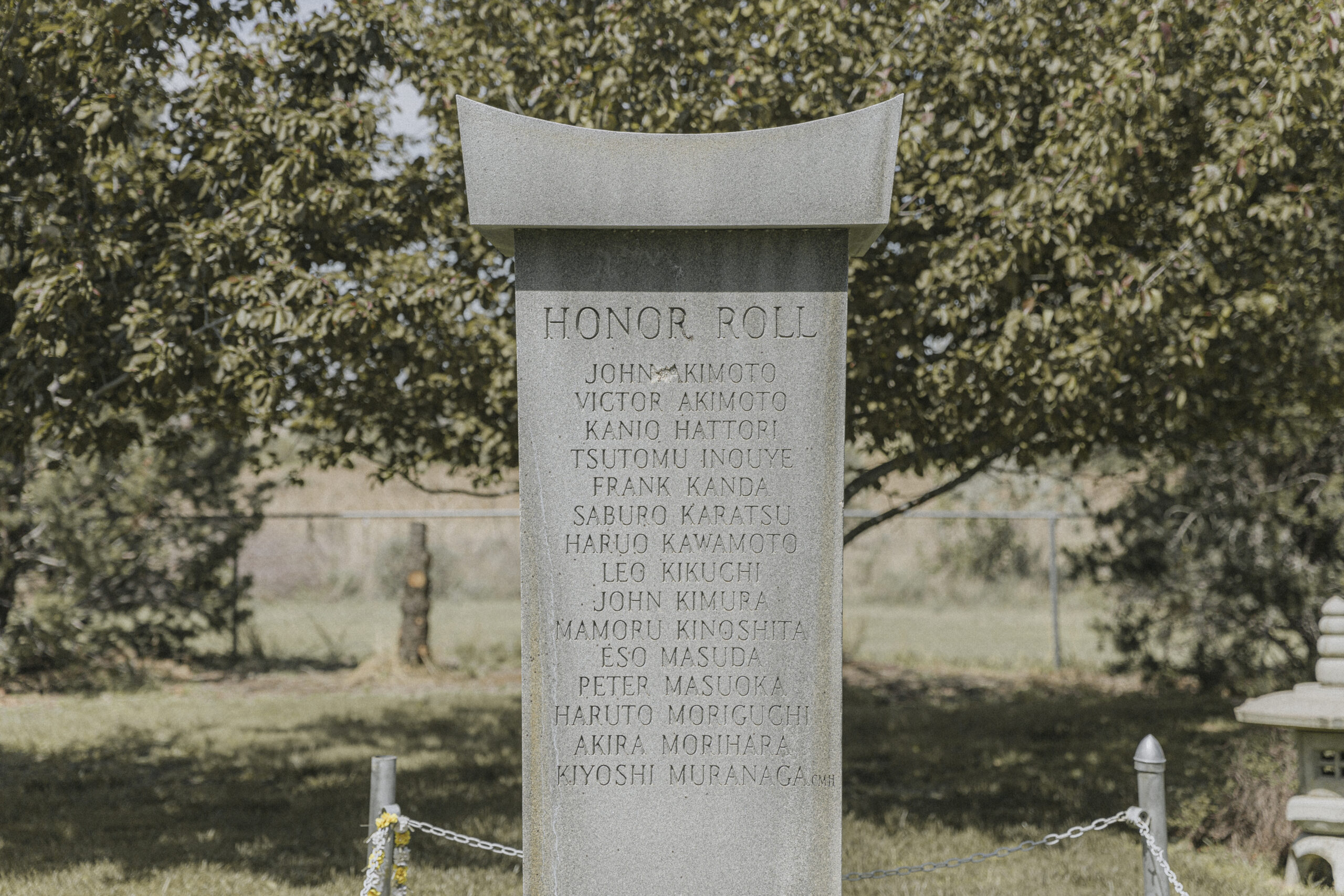

Amache had the highest rate of volunteerism of all the camps, with 953 men and women volunteering or being drafted for military service during World War II. Of these, 105 were wounded and 31 were killed in action.

With the help of local students from Granada and the Amache Preservation Society, what used to be a smattering of headstones bordered by cattle-guard was transformed into a lush cemetery lined with pine trees and Japanese toro lanterns.

Today, Amache is part of the National Park Service, but much of its daily maintenance is managed by the Amache Preservation Society (APS), which consists of volunteer students from the nearby Granada High School. The APS was founded by John Hopper, a social studies teacher who is now the principal at the school.

In 1993, Hopper gave his students an assignment to research the World War II site down the road. This sparked interest in the previously abandoned site and eventually led to the creation of the APS, dedicated to preserving Amache’s history. Initially, the local community did not fully support these efforts—some feared losing local water wells and increased government oversight that might come with a national historic site designation.

Regardless, the APS continued its preservation efforts, and attitudes began to change over time. By the spring of 2000, around 300 people from the Granada community helped the APS clean up Amache’s cemetery, planting over 150 trees, laying sod, and installing a fence.

Today, the APS maintains a small museum in Granada with a collection of objects, documents, and photos related to the camp. It also partners with surrounding schools and organizations to allow Granada High School students opportunities to join local college programs on archaeological excavations and even travel to Japan to learn about Japanese culture while sharing Amache’s history, opening up new experiences for students in this small rural community. Amache highlights the crucial role of community partnerships in preserving historical sites and demonstrates how educators can inspire these preservation efforts.