“My mother was always amazingly supportive of the U.S. When we were traveling, we’d always be singing America The Beautiful and all kinds of patriotic songs.”

— Dale Kunitomi

Masa Fujioka Kunitomi

Nisei

Masa Fujioka Kunitomi was born in Hollywood, CA to two Issei parents. Just hours after the Pearl Harbor attacks, her father—an editor at a Japanese American newspaper—was arrested by the F.B.I. “Not knowing where they were taking him, [his family] wanted him to eat before he left,” Masa’s daughter Kerry recalls. “But the authorities said no, so they gave him a glass of milk—and that was it.” Masa had no knowledge of her father’s location until he was released over seven months later.

At the time Executive Order 9066 was issued, Masa was a first-year student at the University of California, Los Angeles. To stay close to her loved ones, she married her then-boyfriend, Jack Yoshizuke Kunitomi, and within two weeks, they were forced to leave their home. While most families in the area were assigned to the Santa Anita Assembly Center, Jack’s family was sent directly to Manzanar. Masa, with few options, joined her new husband’s family there, while her mother and siblings were sent to Santa Anita Assembly Center and later transferred to Heart Mountain in Wyoming.

Masa arrived in Manzanar at age 21, leaving behind her studies, her aspiration of becoming a teacher, and her close-knit family. While she adjusted to her new life in camp, Masa’s father suffered a life-threatening gall bladder attack and was released from Fort Missoula Internment Camp to reunite with his family at Heart Mountain. Several months later, Jack and Masa volunteered for a seasonal leave program in Idaho and gained permission to transfer to Heart Mountain in November of 1942. Masa was finally reunited with her family in Wyoming, where she and Jack stayed until the war ended and welcomed their first son, Dale.

After the war, Masa dedicated herself to raising a family while taking part-time classes at a local college to resume her dream of teaching. Fifteen years after her studies were interrupted, she earned her teaching degree and went on to teach elementary school for nearly three decades. Masa passed away in 1985, a few years before the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 was passed. She was posthumously awarded an honorary degree from University of California, Los Angeles in 2012.

Masa’s family information as it appears in the Final Accountability Roster for Manzanar. Courtesy of Densho Encyclopedia.

Listen to this portrait.

Dale Kunitomi

Sansei

Dale Kunitomi is the son of Masa Fujioka Kunitomi. He was born in Heart Mountain, where he spent the first year and a half of his life before his family returned to Los Angeles after the war.

Growing up, Dale recalls that his parents rarely spoke about the hardships of their incarceration. “They were just so busy trying to rebuild their lives and live from day to day that there wasn’t time to sit around and talk about what the government should have done,” he says. “My mother was always amazingly supportive of the U.S. When we were traveling, we’d always be singing America The Beautiful and all kinds of patriotic songs.”

Despite his family’s focus on moving forward, Dale remembers growing up with a sense of shame. “I was embarrassed by the fact that this happened to us,” he says. “I can remember, on December 7, always wondering if I should go to school or what would happen to me at school.”

Dale attended his first pilgrimage to Manzanar in 1988. Since his aunt, Sue Kunitomi Embrey—co-chair of the Manzanar Committee—passed away in 2006, Dale and his siblings have continued to help organize the annual pilgrimages, honoring Sue’s legacy.

“I was embarrassed by the fact that this happened to us. I can remember, on December 7, always wondering if I should go to school or what would happen to me at school.”

— Dale Kunitomi

Listen to this portrait.

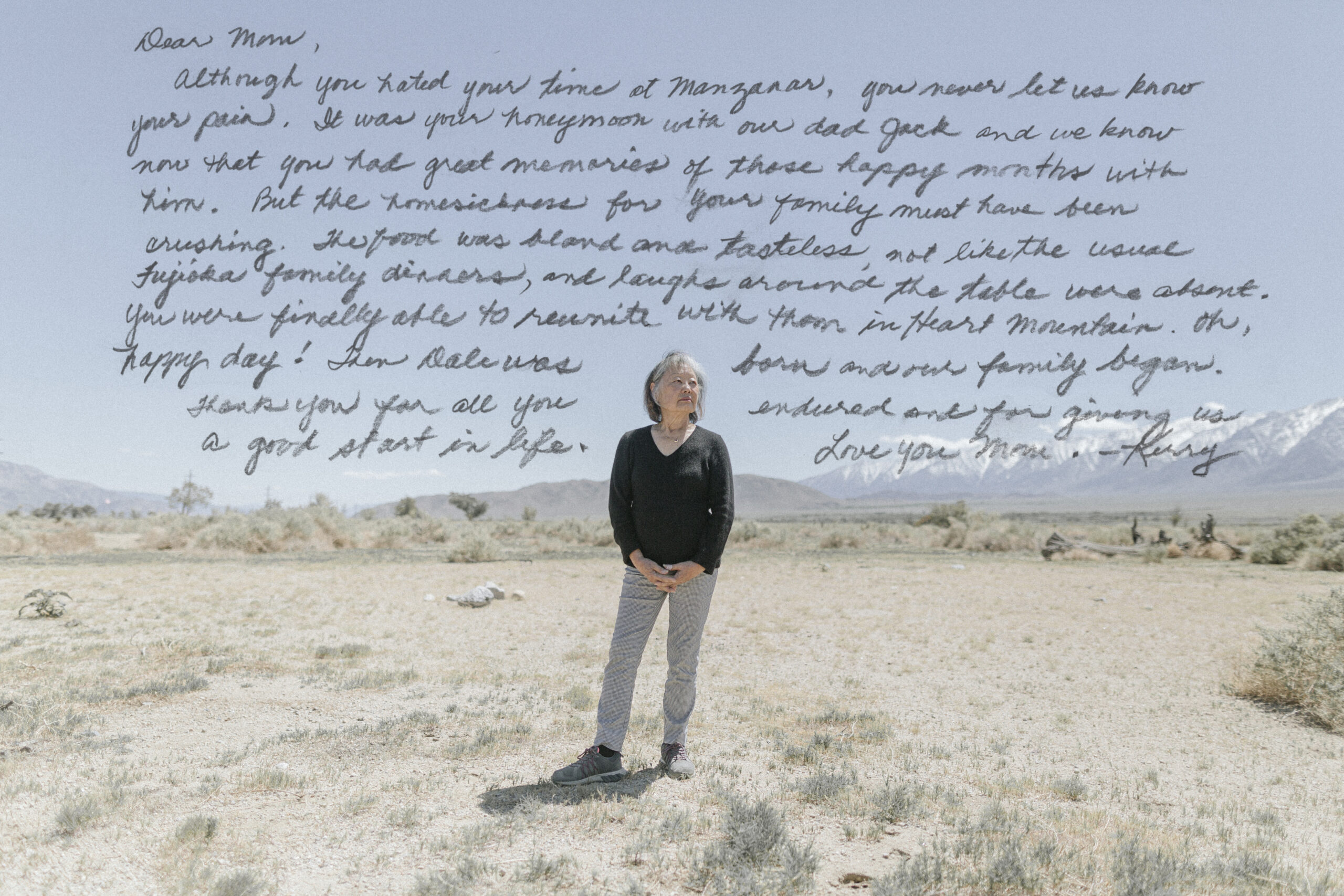

Kerry Cababa

Sansei

Kerry Cababa is the daughter of Masa Fujioka Kunitomi. She was born at the Japanese Hospital of Los Angeles, three years after the end of the war.

Growing up, Kerry often heard her mother refer to her incarceration—which began just two weeks after her marriage to Jack—as her “honeymoon.” Her mother also reflected on how resettlement policies impacted their community after the war. “She said it was bittersweet because it broke up the Japanese ghetto,” Kerry recalls. “It helped to assimilate the Japanese into more of a mainstream America and not come back to Little Tokyo.”

Although Kerry didn’t experience life in the camps like her older brother Dale, she says many Sansei like herself absorbed similar lessons from parents who lost most of their belongings during the war. “When I talk to other Sansei now, we all had similar experiences: we never threw anything away,” she says. “Mottainai. That was what we grew up with. That was the overarching mantra that we heard on everything—paper, scraps of fabric, food.”

Another legacy of the camps was the post-war divide between those who answered “yes-yes” and “no-no” to Question 27 and Question 28 on the loyalty questionnaire. “Some people said no-no’s were just a bunch of cowards, that they didn’t want to fight for their country,” she says. “But we knew these people—and in their mind, that wasn’t the right thing to do at the time. So there was a lot of division.”

“When I talk to other Sansei now, we all had similar experiences: we never threw anything away. Mottainai. That was what we grew up with.”

— Kerry Cababa

Listen to this portrait.

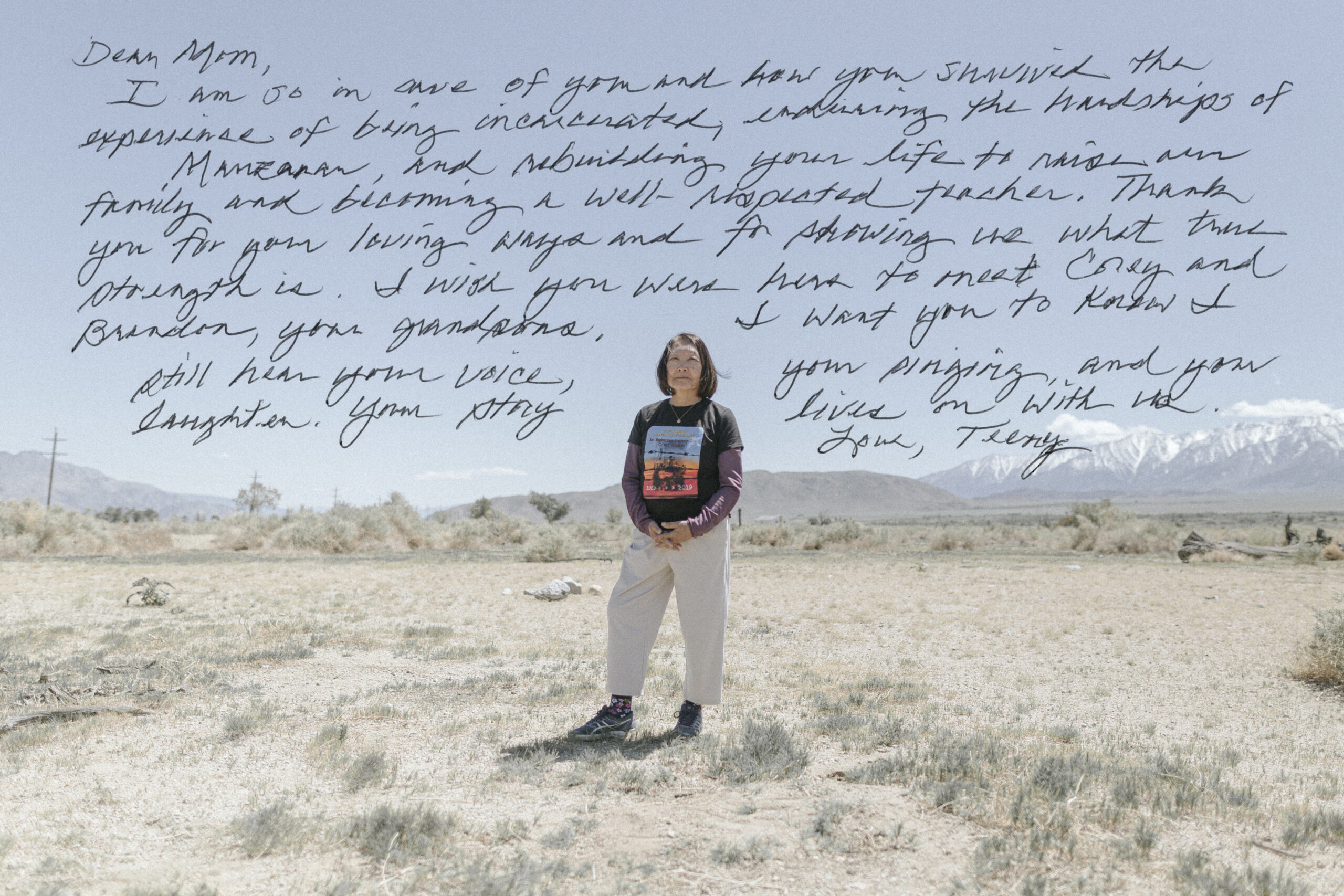

Colleen Miyano

Sansei

Colleen Miyano is the daughter of Masa Fujioka Kunitomi. She was born at the Japanese Hospital of Los Angeles, five years after the end of the war.

Colleen first learned about her family history in high school, when she was assigned a history project to write about an ancestor. “My mom said, if you want an A, you should write about Uncle Ted and the camps,” she recalls. “I thought, ‘What camps? What are we talking about?’” Through her research, Colleen learned about her family’s wartime incarceration and discovered that, despite being held behind barbed wire, her uncle Ted Fujioka had enlisted in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and was killed in action fighting for the U.S.

Colleen says her mother’s easygoing personality belied the harsh realities of camp life. She recounts an instance when her mother, who was an elementary school teacher, spoke about her camp experience with her colleagues. “They asked her, ‘How was your wartime experience?’ And she said, ‘It was the best time of my life, because I was on my honeymoon.’ And they laughed and laughed,” Colleen says. “But then she started to cry. And then everything went quiet.”

Like her mother, Colleen became an educator. Discussing her family history with her students brings her a sense of dignity and pride. “Every family has a different story,” she says. “But every family sacrificed. Every family had an Uncle Ted.”

“They asked her, ‘How was your wartime experience?’ And she said, ‘It was the best time of my life, because I was on my honeymoon.’ And they laughed and laughed. But then she started to cry. And then everything went quiet.”

— Colleen Miyano

Listen to this portrait.

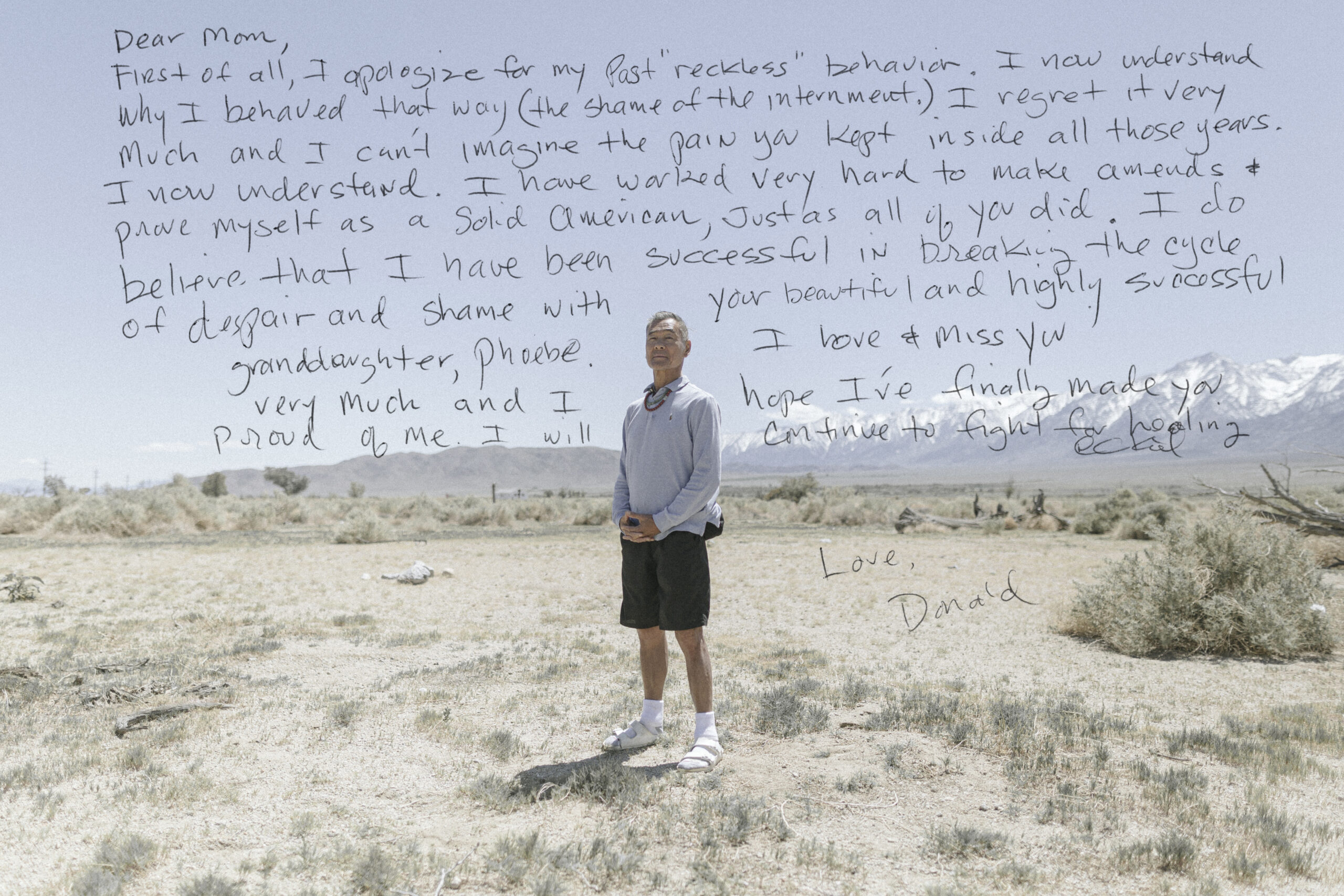

Donald Kunitomi

Sansei

Donald Kunitomi is the son of Masa Fujioka Kunitomi. He was born and raised in Los Angeles.

Donald says his family spent much of their post-war years working to restore a sense of normalcy. “We moved back into the neighborhood and just tried to go back to our pre-war routine,” he recalls. “We went back to playing football, and my sisters became cheerleaders, student body presidents, went to U.C.L.A. They did the whole thing. But the despair, dishonor and shame of the camps was never addressed.”

In 2019, Donald experienced a severe allergic reaction that forced him to take time off from his role as a fire inspector with the Los Angeles County Fire Department. During his recovery, he met a homeopathic doctor who suggested his symptoms might be linked to sugar overconsumption. Reflecting on his childhood, Donald remembered how his mother often prepared sugary desserts for him and his siblings, a habit she developed during her incarceration. “In the camps, the Japanese women tried to keep it so much like home, that one of the things they did […] was scrape together stuff and make a dessert, like a fruit pie,” he says. Since then, Donald has recovered from his condition and attends pilgrimages to further understand the lasting impact of his family’s incarceration.

While the presidential apology that accompanied the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 was pivotal in his family’s journey toward healing, Donald says there is still work to be done. “The government admitted they were wrong. They gave us money. And we have redeemed ourselves to everybody,” he says. “But we have not yet taken that apology really to heart.”