Located in northwestern Wyoming, Heart Mountain was the fourth largest out of the 10 War Relocation Authority concentration camps and the third largest city in Wyoming during its peak population. It is known as the site of the largest single draft resistance movement in U.S. history.

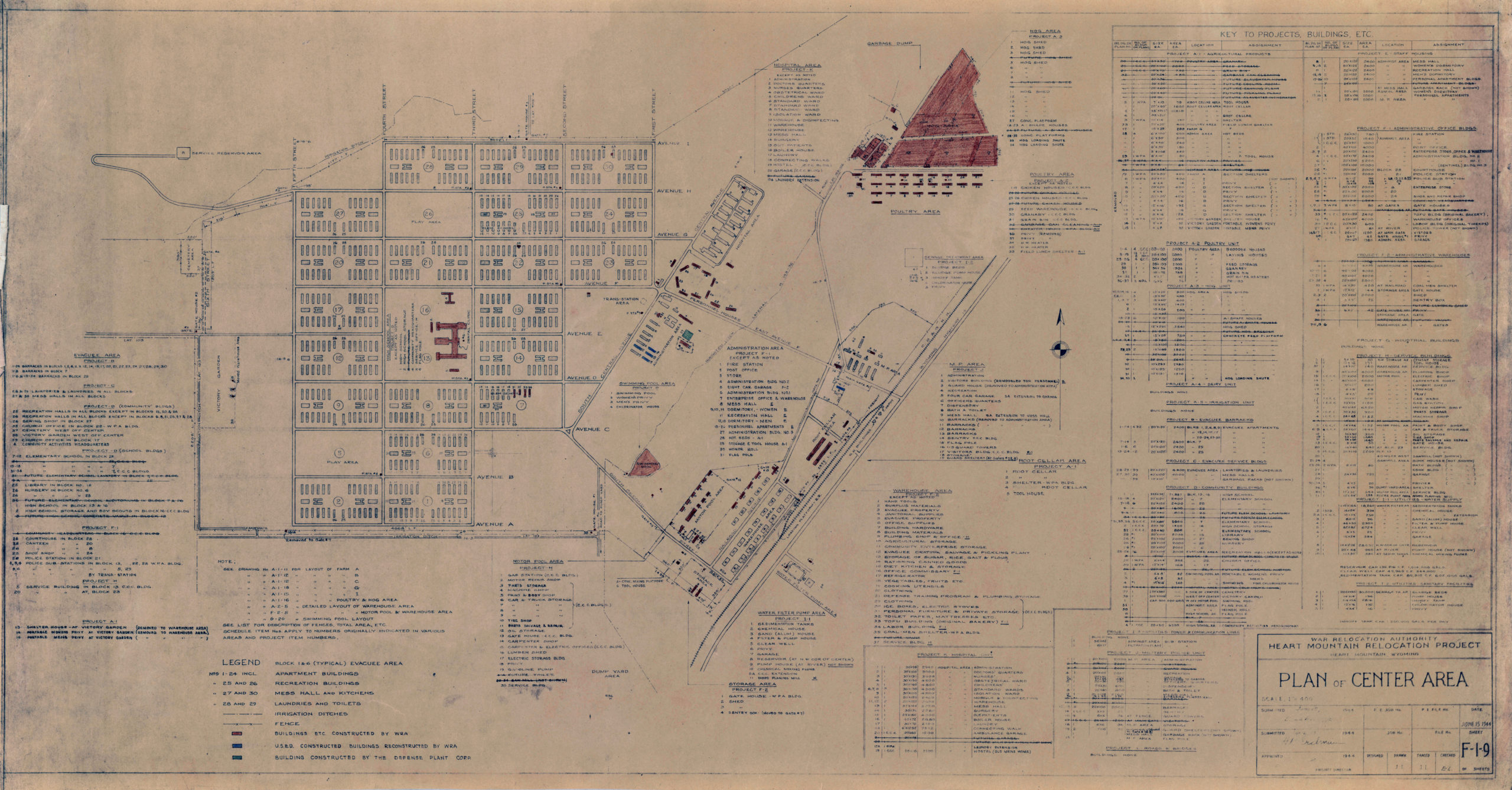

The War Relocation Authority‘s master plot plan for Heart Mountain. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

The concentration camp was situated on 46,000 acres of sagebrush desert near the Shoshone River. The arid landscape was frequented by debilitating dust storms and night time temperatures that dipped to 30 degrees below zero during the winter months. Eight miles to the west was the iconic Heart Mountain, a limestone butte that many incarcerees remember as a distinct backdrop behind the sprawling barracks in which they lived.

Barracks at the Heart Mountain concentration camp with view of Heart Mountain in the distance. September 18, 1942. Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration.

A section of the original Heart Mountain concentration camp was designated a National Historic Landmark in 2006 and is currently maintained by the Heart Mountain Interpretive Center. May 27, 2022.

The majority of the camp—which included over 450 barracks and a 150-bed hospital complex—was hastily built over a two-month period by local civilians lured by newspaper ads that read, “If you can drive a nail, you can qualify as a carpenter.” Prior experience in construction was not required. Speed was often prioritized over quality, with some laborers bragging that it only took them 58 minutes to build one barrack. When incarcerees began to arrive in August of 1942, many were forced to live in poorly built barracks made of tar paper siding with hastily installed doors and windows that did not close completely. Incarcerees used rags and newspaper to stuff the cracks between the wall boards to stay warm.

Heart Mountain is one of the few concentration camps with buildings still standing today. The remaining structures include a hospital boiler house with an intact smokestack, a hospital warehouse, a hospital mess hall, and an administrative staff housing unit.

Hastily built camp buildings offered little protection from Wyoming’s harsh weather conditions.

Little remains of what was once a 150-bed hospital complex. Staffed by incarceree doctors, the hospital provided medical care to the camp population, including the delivery of 556 babies.

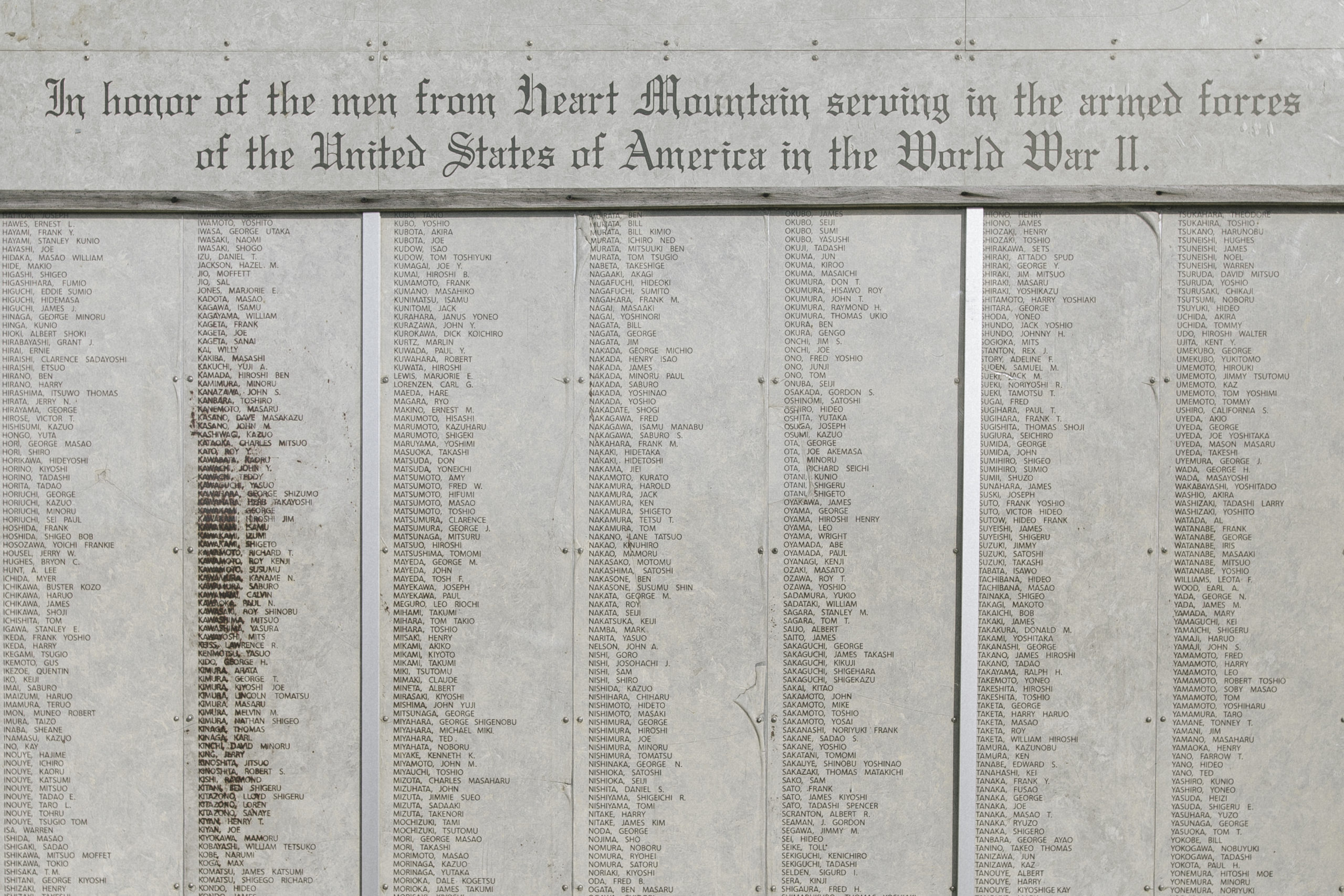

A total of 385 incarcerees from Heart Mountain served in the U.S. military. While Heart Mountain is often associated with its draft resistance movement, it also has the distinction of having the highest number of incarcerees who won the prestigious Medal of Honor.

Many of the facilities at Heart Mountain, including the garment factory, cabinet shop, sawmill, and silk screen shop, were staffed with Japanese American incarcerees, who worked for a small salary of $12-$19 a month. Nisei incarcerees were permitted to work, while Issei incarcerees were not. For many Issei, the camp experience was one of forced displacement followed by involuntary idleness.

The hospital complex and schools on site hired both Japanese Americans and Caucasians to serve as doctors, nurses, teachers, and teacher aides. However, wages differed widely: Japanese American doctors were paid $19 per month, while Caucasian nurses were paid $150 per month.

Some incarcerees worked as farmers on the 1,100 acres of farmland on the southeastern corner of the property. Despite the arid climate and doubt from local farmers, Japanese American incarcerees yielded 1,065 tons of produce during their first harvest. They were not only able to sustain their fellow incarcerees, but also able to yield enough surplus crops to be stored in two 300′ x 40′ root cellars—which they also built—or distributed to the other concentration camps. Known as the “Heart Mountain Miracle”, incarcerees at Heart Mountain turned arid Wyoming soil into lush farmland in less than a year and introduced an array of new crops to the region.

The War Relocation Authority utilized incarceree labor to farm and produce the camp population’s food. Root cellars like this stored surplus crops to be distributed to the camp and sent to the other camps.

This 300′ x 40′ root cellar was built by incarcerees using only hand tools and a single excavator. From harvesting the timber to constructing the cellar, Japanese American incarcerees completed every step of the build process. It is the only surviving camp structure built entirely by Japanese American incarcerees from start to finish.

Aside from agricultural work, the War Relocation Authority also utilized incarceree labor to complete the Shoshone Project, a local irrigation project that had been abandoned when the U.S. entered World War II. Japanese American incarcerees built over 5,000 feet of the canal, which continues to feed into the farmlands in the Big Horn Basin today.

Why is Heart Mountain significant?

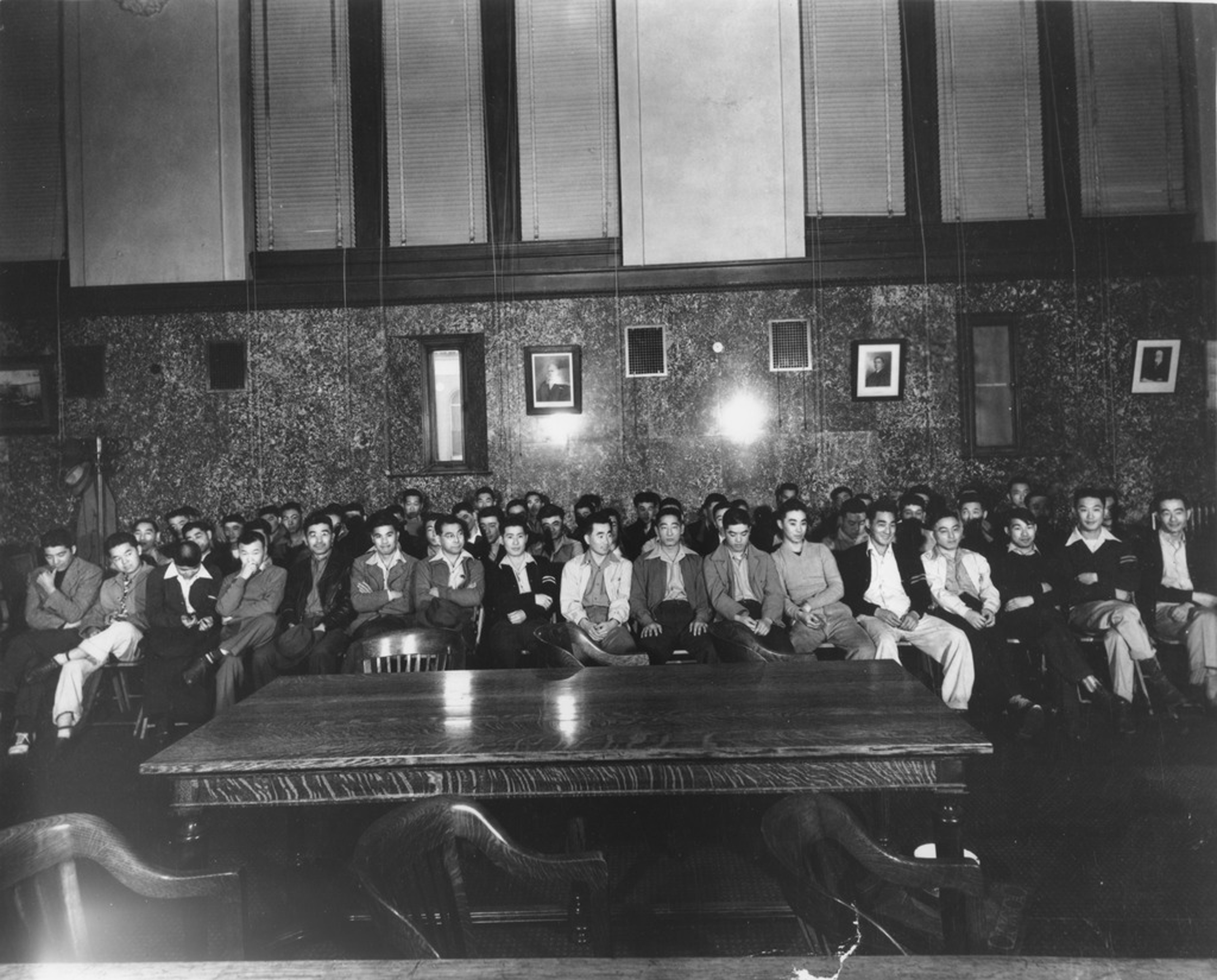

Sixty three members of the Fair Play Committee appear in a federal district court in Cheyenne, WY for their first day of trial. Courtesy of Densho Encyclopedia.

Although there were draft resistance movements in the other concentration camps, Heart Mountain had the highest number of draft resisters per capita and is known as the site of the largest single draft resistance movement in U.S. history.

In January of 1944, the U.S. government announced that U.S.-born incarcerees would be eligible for compulsory enlistment in the U.S. Army under the Selective Service Act of 1940. This ignited anger amongst incarcerees who believed that they should not be forced to serve in the military while their civil rights were being violated. The following month, a group of incarcerees formed an organization called the Fair Play Committee to resist the draft and to demand a restoration of their civil rights as a precondition for their military service. Sixty three members of the Fair Play Committee were arrested and sentenced for up to four years in federal prison.

In total, the Heart Mountain draft resistance movement resulted in 85 arrests. Although draft resisters were later granted a full pardon by President Harry Truman after the war, they were criticized by some members of the Nikkei community and the broader public for decades after the war.