Located in central Utah about 135 miles southwest of Salt Lake City, the Central Utah Relocation Center—known as Topaz—was the second least populous War Relocation Authority concentration camp with a peak population of 8,130 incarcerees.

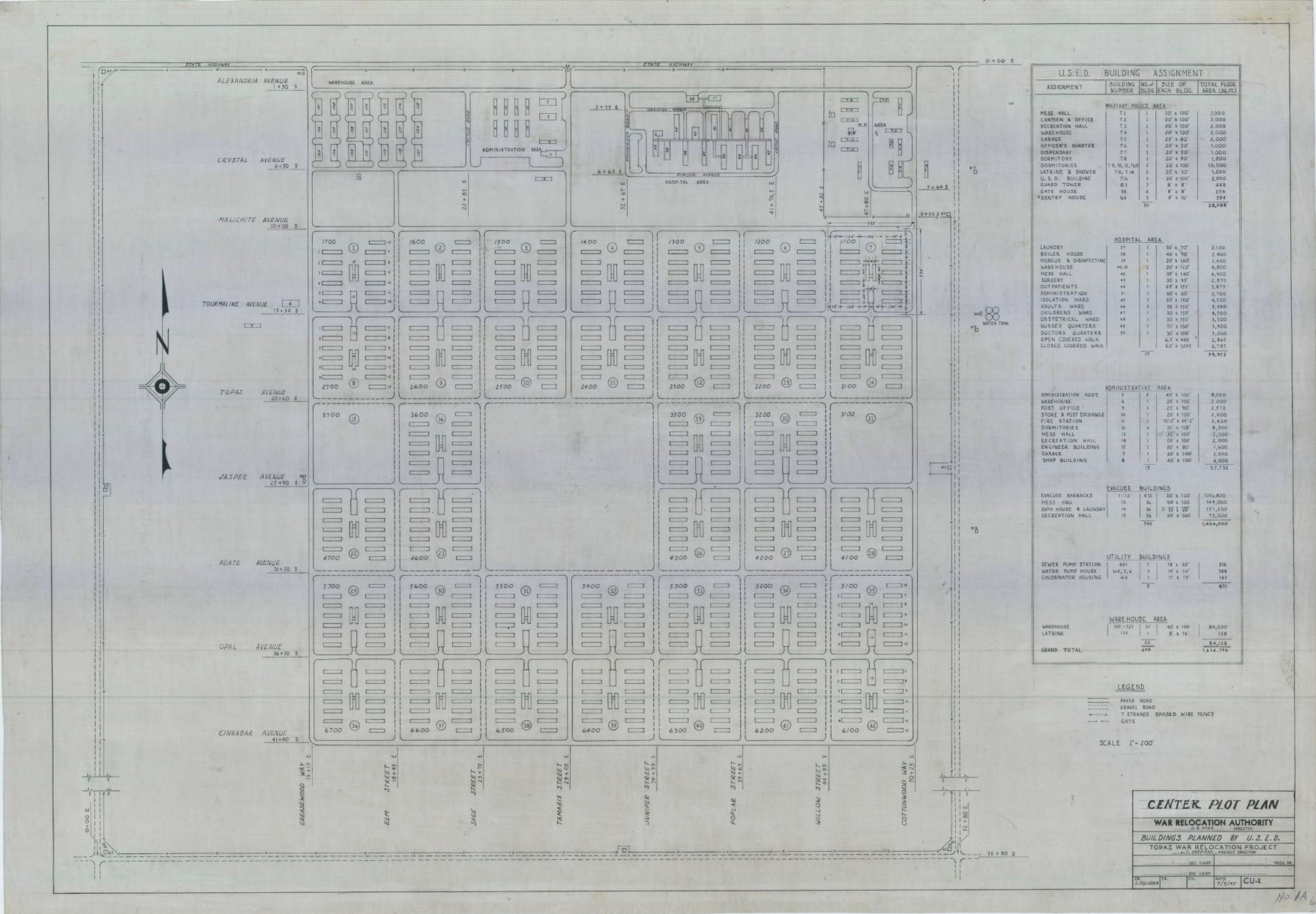

The War Relocation Authority‘s master plot plan for Topaz. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

The concentration camp was situated on 19,800-acres in the Sevier Desert, on what was originally the ancestral home of the núuchi-u people. Topaz experienced volatile weather fluctuations, with summer temperatures soaring up to 105 degrees and winter temperatures dipping below zero. Choking dust storms were a significant problem at Topaz, more severe than those at other War Relocation Authority concentration camps.

The Topaz concentration camp with Thomas Range in the background. March 14, 1943. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

The Topaz concentration camp with Thomas Range in the background. July 23, 2022.

When the first Topaz incarcerees arrived in the fall of 1942, they found much of the camp still under construction. Many barracks were unfinished, forcing some families to double up with others or sleep in public quarters like mess halls and hospital buildings. Others were ordered to sleep in barracks that lacked roofs, mattresses, and blankets. By October, nighttime temperatures had fallen to 10 degrees—yet, many barracks were still missing wall boards and stoves.

There was also a severe coal shortage that lasted into November. A company contracted to supply 25,000 tons of coal to the camp had delivered only 40—less than one percent of the promised amount—causing chaos within the camp administration. Incarcerees were subject to shortened school days and two-hour shower windows based on heat availability.

Snowy conditions at the Topaz concentration camp. Circa 1943. Courtesy of the Terakawa Family Collection.

Food supplies at Topaz were also unreliable. In the spring and summer of 1943, the camp faced a meat supply shortage leading to a diet of organ meats like livers, hearts, and tripe. This lasted for months until beef and pork were finally served in August of 1943.

The barracks at Topaz were constructed of pine and elevated from the ground on stacked wood scraps, offering little protection from the harsh climate. Incarcerees coped by digging subterranean spaces to escape the weather, building furniture out of scrap lumber to make their barracks more livable and beautifying their camp by planting ornamental gardens.

Unlike other War Relocation Authority camps, the relationship between the incarcerees and the local community was relatively amicable. Some credit this to many of the local residents being Mormon, a community that has also experienced persecution.

Once a populous camp housing over 8,000 incarcerees, the Topaz concentration camp now consists of two monuments, some building foundations and portions of the perimeter fence. It is currently owned by the Topaz Museum, a local organization.

Topaz was notable for its robust art school, started by artist and University of California professor Chiura Obata. Notable artists who taught at the school include Hisako Hibi, Frank Taira, Miné Okubo, and Byron Takashi Tsuzuki. Citizen 13660—Miné Okubo’s illustrated memoir published in 1946—was instrumental in helping to preserve the memory of the Japanese American incarceration experience in the early postwar period.

Why is Topaz significant?

James Hatsuaki Wakasa‘s funeral. April 19, 1943. The man accused of killing Wakasa—Private First Class Gerald Philpott—was found not guilty in a court martial trial. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

The Wakasa Monument was unearthed in 2021 by the Topaz Museum Board, a local organization that owns 634 acres of the Topaz site.

Topaz is known as the site of the fatal shooting of James Hatsuaki Wakasa, an Issei incarceree, who was shot and killed by a guard while walking his dog inside the fence of the camp. The guard, a 19-year-old private named Gerald Philpott, was found not guilty in a court-martial trial.

Up to 3,000 incarcerees attended Wakasa’s funeral. A group of Issei incarcerees erected a stone monument in his memory, but camp authorities ordered them to destroy it. In an act of defiance, the Issei incarcerees buried the monument instead, leaving a small part of it exposed.

The monument was rediscovered almost eight decades later, when Topaz descendant Nancy Ukai found a 1943 map showing the exact location of Wakasa’s body after he was shot, and archaeologists Jeff Burton and Mary Farrell traced the location of the buried monument using the map.

In 2021, a contractor hired by the Topaz Museum Board—a local organization that owns 634 acres of the Topaz site—allegedly excavated the monument without archaeologists or Japanese American stakeholders present. The same year, a group of Japanese Americans—many of them Topaz descendants—formed an organization called the Wakasa Memorial Committee to protest the excavation.