“I would have been willing to swear unqualified allegiance to the U.S. if the government had assured me and my wife and child that we could be free and safe like U.S. citizens.”

— Tadayasu Abo

Tadayasu Abo

Nisei/Kibei

Tadayasu Abo was born in 1911 in Selleck, WA, a company town owned by Pacific States Lumber Company. At age seven, he moved with his family to Onomichi, their hometown in Hiroshima Prefecture, Japan. At age 16, Tadayasu returned to Washington alone and worked as a lumberman during the winters and an oysterman during the summers.

When he was in his 20s, Tadayasu briefly returned to Onomichi for an arranged marriage with Yukiko, a family friend. The couple eventually settled in Oyster Bay, WA, where they lived alongside other Japanese American families to work for the J.J. Brenner Oyster Company. There, they welcomed their first son, Joe (Masatsugu).

Life took a dramatic turn after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Prior to the bombing, Tadayasu had registered for the draft board to serve in the U.S. military. After the bombing, however, he was reclassified as IV-C, a designation for aliens, despite being a U.S. citizen. Not long after, Yukiko was physically attacked while walking down the street in Olympia. “[She] was kicked by a white woman, and my wife had great fears of persecution from hostile communities,” Tadayasu recalled in an affidavit he prepared during a class action lawsuit after the war. Ultimately, Tadayasu and Yukiko—along with their two-year-old son, Joe—were displaced from their home and sent to Tule Lake, where their second child, Nancy (Kazuko), was born.

Life inside Tule Lake was filled with uncertainty and fear. When the loyalty questionnaire was distributed in 1943, there was widespread confusion about Question 27 and Question 28. Hearing rumors that answering “yes” to the questions could lead to involuntary relocation and potentially endanger their relatives in Japan, Tadayasu and Yukiko answered “no reply” and became classified as “no-no’s.” Tadayasu later explained in his affidavit, “I would have been willing to swear unqualified allegiance to the U.S. if the government had assured me and my wife and child that we could be free and safe like U.S. citizens.”

Pressured by pro-Japan groups within the camp, Tadayasu ultimately renounced his U.S. citizenship. “With all the trouble at camp and no protection for us against gang violence, nor any protection outside, it looked like getting the [renunciation] forms was the only thing to do for being safe,” he shared in his affidavit. Tadayasu was one of 5,589 incarcerees who renounced their U.S. citizenship during these turbulent years.

After the war, Tadayasu joined a class action lawsuit brought by civil rights attorney Wayne M. Collins to restore his U.S. citizenship, arguing that his renunciation had been made under duress. Because his last name was alphabetically first of the 2,300 plaintiffs, the class action suit was titled, Abo v. Clark. This case was part of a series of legal efforts that ultimately helped Tadayasu and thousands of other Japanese Americans restore their U.S. citizenship by canceling their renunciations.

Tadayasu and Yukiko spent their post-war years in Oyster Bay, where Ron and Lucy were born. Their birthright citizenships were not restored until 1957. Tadayasu did not openly discuss his renunciation or the litigation process with his children before passing away in 1989.

Tadayasu’s family information as it appears in the Final Accountability Roster for Tule Lake. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

From left to right: Tadayasu and his wife Yukiko with their children Joe (Masatsugu) and Nancy (Kazuko) in front of the barracks at Tule Lake. Courtesy of the Abo Family Collection.

Listen to this portrait.

Joe Masatsugu Abo

Sansei

Joe Masatsugu Abo is the first born child of Tadayasu Abo. He was born in 1939 in Olympia, WA and raised in Oyster Bay, WA. When Joe was two years old, he and his family were displaced from their home and sent to Tule Lake.

While Joe’s memories of Tule Lake come to him in fragments, certain moments stand out, like when his parents ordered him a toy from a mail order catalog. “My parents bought me—of all things—a little wind-up submarine, and I played with it in a galvanized steel tub in our barrack room,” he says. He also fondly recalls sneaking a raw potato from the mess hall with the other kids. Since the 1980s, Joe has made numerous pilgrimages to Tule Lake with his siblings as well as his immediate family.

One of the most meaningful encounters with his family history took place at the Smithsonian Museum during their 2019 exhibition Righting a Wrong: Japanese Americans and World War II. “I saw a copy of the Wayne Collins class action suit and there was my father’s name right there—Tadayasu Abo v. Clark,” he says. “I don’t know how many thousands saw that. Of course, they wouldn’t have any idea who my dad was.”

Joe reflects on how his father never spoke openly about his renunciation. “Dad was not a community leader type of person. I don’t remember any kind of celebration when he received news of getting his citizenship back. This is my feeling—he felt ashamed about it. He never spoke about it to anybody,” he says. “I do remember he was a long-time member of the A.C.L.U., probably because of Wayne M. Collins. I am also an A.C.L.U. member because of Wayne M. Collins.”

“I don’t remember any kind of celebration when he received news of getting his citizenship back. This is my feeling—he felt ashamed about it. He never spoke about it to anybody.”

— Joe Masatsugu Abo

Listen to this portrait.

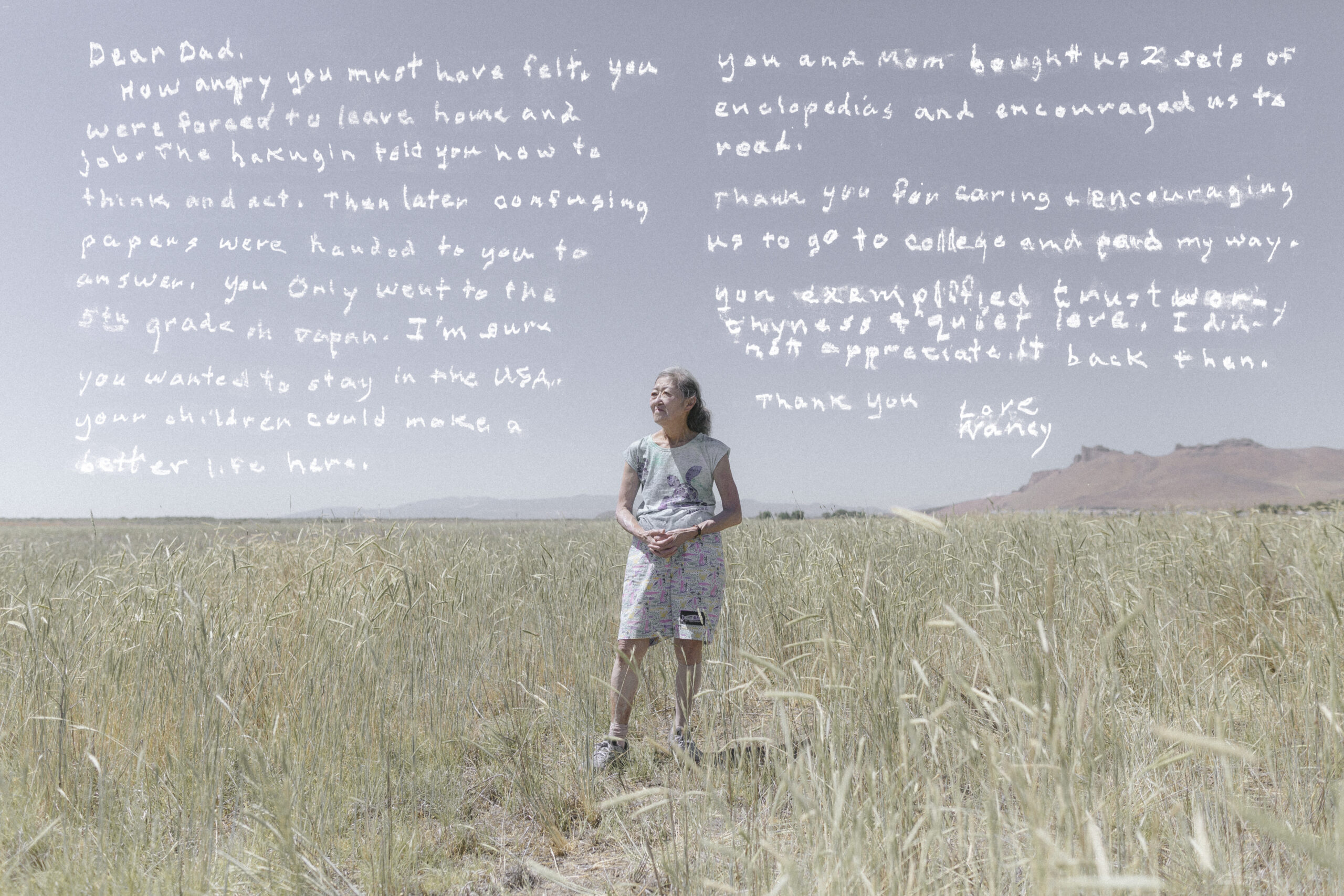

Nancy Kazuko Nance

Sansei

Nancy Kazuko Nance is the second born child of Tadayasu Abo. She was born in 1943 in Tule Lake.

Though she was an infant at the time and has few memories of Tule Lake, Nancy vividly recalls the train ride after their release. “I remember the red velvet seats because they were fancy,” she says, reflecting on the unusual texture after spending her entire life confined within the camp. “That’s all I remember.”

Growing up, her father rarely spoke about their incarceration. The only tangible link to that period of their life was his recipe book from working as a cook in the camps. “He brought home an old recipe book from the mess hall and used it to make Parker House rolls,” she recalls. “He didn’t talk about camp, and neither did Mom. And we didn’t ask.”

After receiving their reparation checks following the passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, Nancy says she, her brother Joe, and their parents shared their funds with Lucy and Ron who were born after Tule Lake.“I gave some to my younger brother, Ron, but he returned it, saying he had enough money,” she recalls. Her father chose to use part of his reparations to build a home with a garden for his wife, Yukiko.

“He didn’t talk about camp, and neither did Mom. And we didn’t ask.”

— Nancy Kazuko Nance

Listen to this portrait.

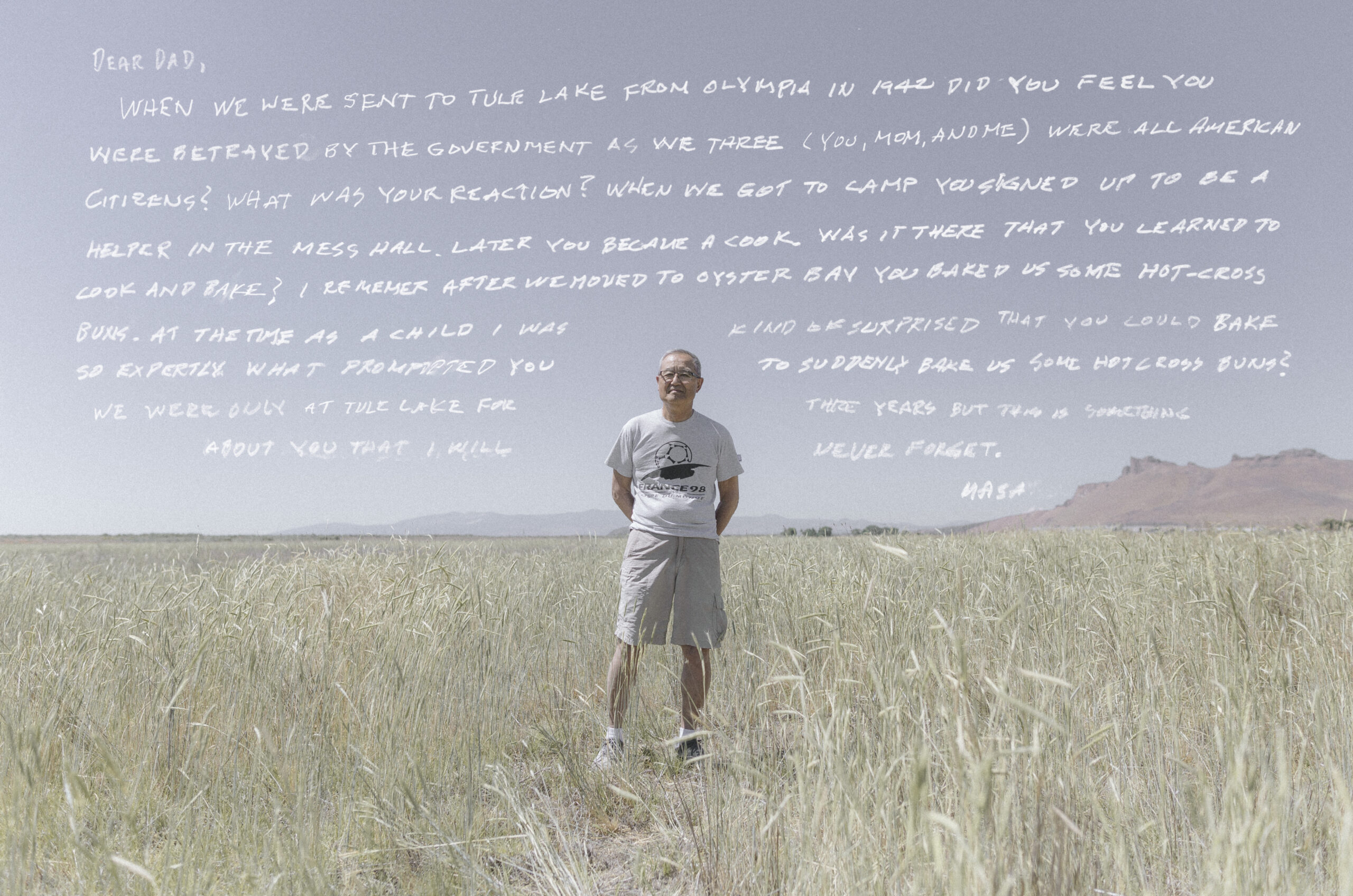

Ron Masaru Abo

Sansei

Ron Masaru Abo is the third born child of Tadayasu Abo. He was born in 1947 in Olympia, WA, two years after the end of the war.

Ron describes his childhood as one filled with exploration. “We didn’t have any kids nearby, so I would make up stories and act them out,” he says. “You really develop an imagination when you’re walking in the woods, heading down to the beach, or making little fires and cooking weenies.” The Abo family lived in company housing provided by the oyster company where his parents worked. “It was a small, two-bedroom home, more like a tiny cabin,” Ron recalls. He remembers his parents working long hours in the culling house, cleaning oysters. “They would clean and get all the debris out of the oysters. They did that all day, side by side.”

Ron shares that his parents rarely spoke about their wartime incarceration. “They just never talked about it. I think it was a bad experience. It brought back bad memories,” he says. He believes his father’s renunciation was influenced by pressure from pro-Japan factions within the camp. “There was a group of individuals—the Hoshi Dan—who were threatening some of the families who were thinking about not saying no-no,” he says. “I think wanting to do the right thing can be very difficult if you have a family.”

Although his father never openly discussed his renunciation, Ron notes a shift in the cultural perception of No-No Boys. “Before, the No-No Boys were considered rats by the Japanese. And now, I think the culture has changed,” he says. “The larger culture said, maybe they were heroes, maybe we should celebrate the fact that they stood up and said, ‘hey, this is crazy.’”

“I think wanting to do the right thing can be very difficult if you have a family.”

— Ron Masaru Abo

Listen to this portrait.

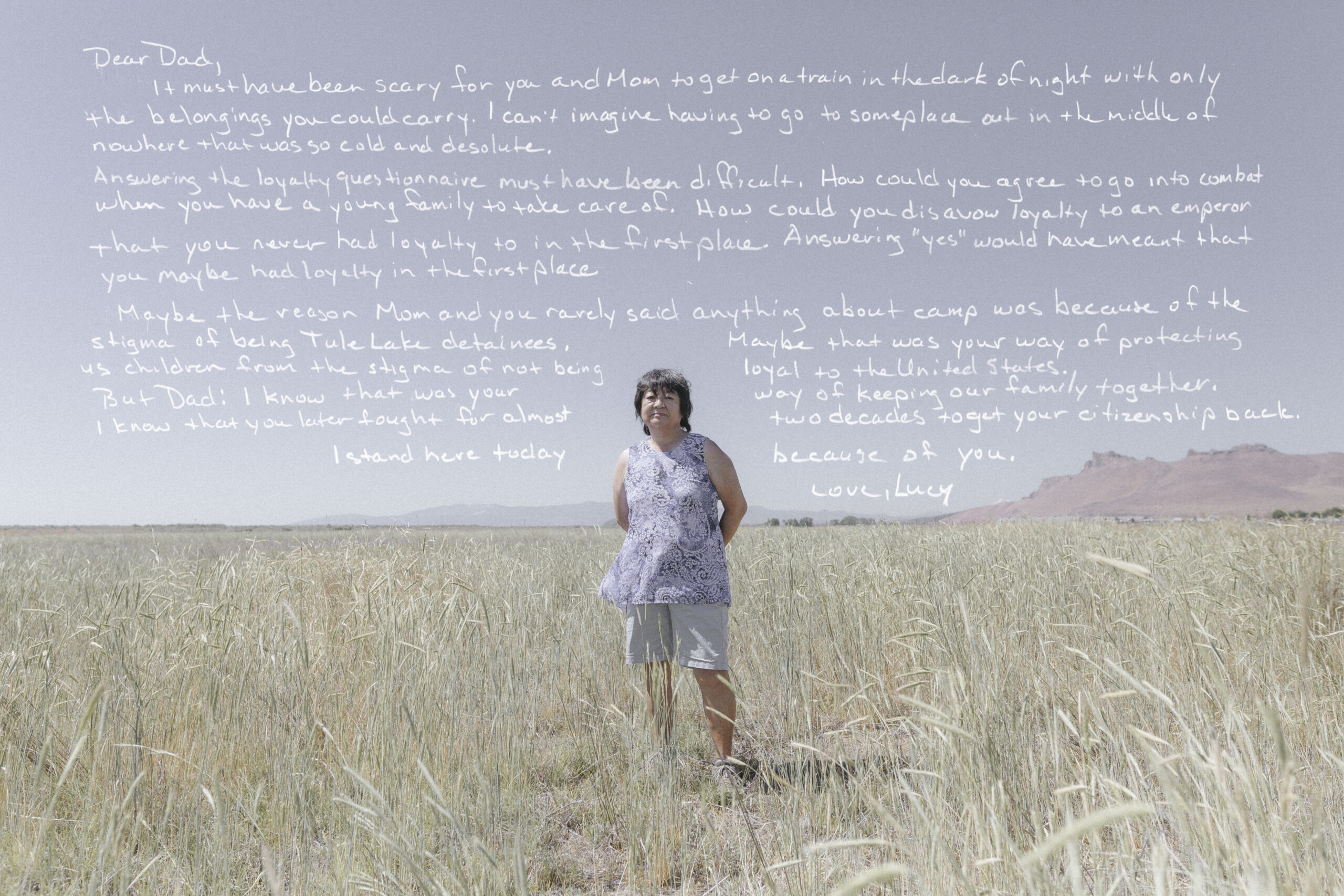

Lucy Akemi Abo

Sansei

Lucy Akemi Abo is the fourth born child of Tadayasu Abo. She was born in 1954 in Olympia, WA and raised in Oyster Bay, WA.

When Lucy was six years old, she came across an old photograph of her father in a family album. “It was a picture of my father standing with a little bird on his shoulder,” she recalls. “And you could see in the background, there was a tar paper shack.” When she asked her mother about it, she simply replied that it was from “camp.” Only years later did Lucy come to understand the full story. “We had no idea that they had lost their citizenship until I was a lot older,” she says.

Although her parents spoke Japanese to each other, they discouraged their children from learning it. “Japanese wasn’t something that my parents encouraged us to learn because, of course, at that time they were trying to get their citizenship back,” she says. “They were trying to show that you don’t need to learn Japanese or Japanese ways. It was more about assimilation.”

Lucy came to appreciate the depth of her father’s involvement in the Japanese American community when she witnessed the significant turnout at his funeral in 1989. “I had no idea that my parents knew all these people,” she says. “I always thought [my dad] was a quiet man. He didn’t seem to really want to get involved with things. […] But everyone remembered him as a very caring man who was always willing to help them, that he was just a wonderful person.”